On February 7, 1998, Campo Las Palmas, the Dodgers’ baseball academy in the Dominican Republic, with banners featuring Hideo Nomo, Mike Piazza, Eric Karros and Raul Mondesi.

State-of-the-Art Campo Las Palmas Baseball Academy Led Dominican Development

By Brent Shyer

Dodger Vice President and General Manager Al Campanis acquired Pedro Guerrero from the Cleveland Indians via a trade in 1974. When Guerrero, from the Dominican Republic, started to produce consistently for the Dodgers in the 1980s, Campanis realized that the Dominican market was still largely untapped, but with the potential to develop a considerable amount of talent.

The Pittsburgh Pirates were known as aggressive talent seekers during a period of 1965-1977 and had signed 100 players from the Dominican Republic. The Sporting News, “Where Talent is Hatched,” July 12, 1980 The Toronto Blue Jays were also keenly interested in discovering young Dominican talent and had scouts combing the area.

Campanis asked Ralph Avila, Dodger scout for Latin America, to establish baseball’s first development program in the Dominican Republic. Mark Heisler, Los Angeles Times, April 12, 1987 As development efforts continued and with emerging competition, Avila and Campanis discussed the possibility of the Dodgers having a dedicated year-round complex that would serve the purpose of scouting young Dominican talent, while housing, feeding and educating the players. Internationally-minded Dodger President Peter O’Malley agreed with the idea.

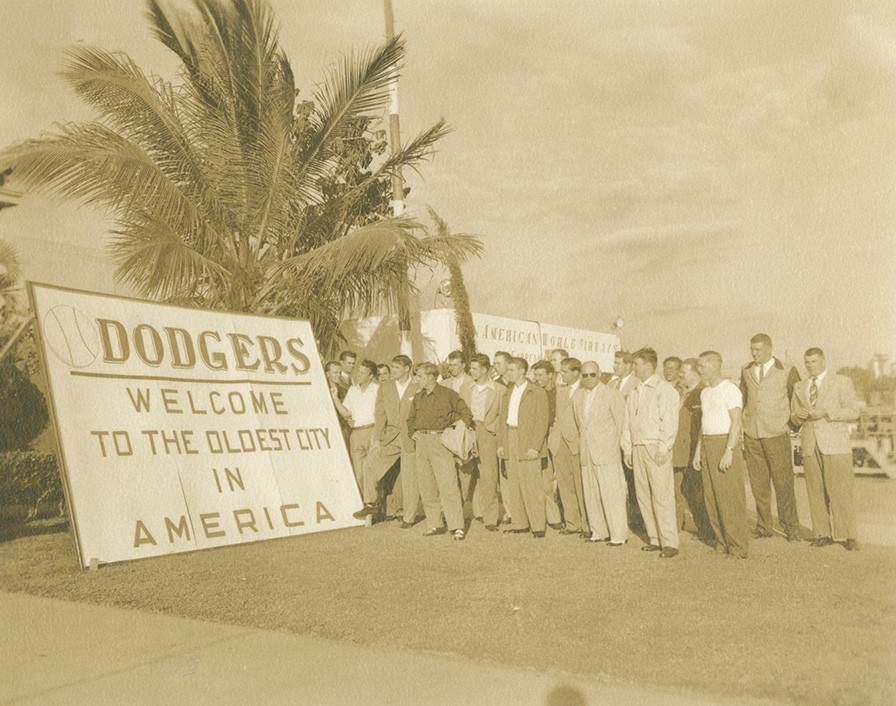

The Dodgers have a long history with the Dominican Republic. In 1948, the city of Ciudad Trujillo was the site of the major league Dodgers’ Spring Training camp. The city was officially named for Rafael Trujillo, who was essentially in power for 31 years, both as Dominican Republic President from 1930-1938 and again from 1942-1952, while controlling the country as an unelected military strongman at other times. In 1936, the name of Ciudad Trujillo, the capital city, was officially recognized in tribute to the president. But, just six months after Trujillo’s assassination, the name was changed in November, 1961 to Santo Domingo, which it had previously been called since it was founded in 1496.

In 1948, the O’Malley family visited Ciudad Trujillo during the Dodgers’ spring training activities for a week. “The last vacation I had was in 1948 when the Dodgers trained in Ciudad Trujillo,” said Walter O’Malley, at the time Dodger Vice President and General Counsel.” Arch Murray, The Sporting News, November 8, 1950 O’Malley, his wife Kay and their two children Terry and Peter were on the trip to the Dominican.

The Brooklyn Dodgers are heartily welcomed as they arrive in Ciudad Trujillo (Santo Domingo), Dominican Republic in the spring of 1948 for training camp.

Photo by Barney Stein

That year 1948 was an important one for the Dodgers. Jackie Robinson returned for his second season in the majors after his 1947 Rookie of the Year award-winning debut, which forever changed baseball. When Robinson stepped onto the playing field at Ebbets Field, Brooklyn on April 15, 1947 as the first African American, the Dodgers and baseball were taking the lead in integration and civil rights. In 1947, the Dodgers and Montreal Royals (Triple-A team) had trained in Havana, Cuba because it was considered a place where Robinson and other African Americans including Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Roy Partlow and Dan Bankhead could stay, very different from when the Royals trained and stayed in Daytona Beach, Florida, under Jim Crow laws, the year before.

While the Dodgers would establish training base Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida for their 26 minor league affiliates in 1948, the major league Dodgers and the Royals were preparing in the Dominican. But, the Dodgers did play the Royals for two games at Dodgertown that spring with Robinson and catcher Campanella on the big league roster. Because the players were all housed on base in the former U.S. Naval Air Station barracks, which had been abandoned at the end of World War II, Dodgertown has been recognized as Major League Baseball’s first fully-integrated spring site in the South. By the spring of 1949, the Dodgers transferred all their training operations – major and minor leagues – to Dodgertown and remained in the “town within a town” for 60 springs.

In 1969, Manny Mota of Santo Domingo made his first appearance with the Dodgers. He had an impressive career, becoming well-known as a pinch-hitter extraordinaire, setting the then major league record for career pinch-hits with 150 in 1980. He played until 1982. Dodger fans were enamored with Mota and his uncanny ability to walk off the bench cold in a clutch situation and deliver. It was said by Hall of Fame Dodger broadcaster Vin Scully that “Mota could wake up on Christmas morning and hit a line drive to center.” Manny Mota, baseball-reference.com Quite a compliment for a man with humble beginnings. It has been preached to young Dominican batters as a mantra that “you can’t walk your way off the island,” meaning they have to be aggressive at the plate. LaVidaBaseball.com, March 20, 2017

The Dodgers were always searching for baseball talent and their pursuit was on a worldwide basis. Friendships were frequently the path to finding potential stars. In 1972, the Dodgers put together a working agreement with Tigres de Licey, Dominican Republic Winter League team. Licey was operated by its President Monchin Pichardo. Over the next 20 years, Licey would win 10 championships and 6 Caribbean Series.

The first year of the agreement, Tommy Lasorda was the manager for the Tigres. Lasorda was manager of the Triple-A Albuquerque Dukes, who won the Pacific Coast League Championship. He then took Licey to the Dominican Winter League title in 1972-73 and to the Caribbean Series championship in 1973. Winning the Caribbean Series represented an immense sense of pride for a baseball-frenzied nation, especially since Venezuela, Mexico and Puerto Rico were the opponents. Lasorda was manager the following season and won the Dominican Winter League championship back-to-back.

In the 1970s, many young Dodger players were developed during winter ball in the Dominican, including such recognizable names as Steve Garvey, Steve Yeager, Charlie Hough, Rick Rhoden, Doug Rau, Von Joshua, Tom Paciorek and Jerry Royster. Mota played for Licey when Lasorda managed in 1972-73 and later managed the club to back-to-back winter league championships (1982-83, 1983-84).

On March 22, 1997, Licey Tigres owner Monchin Pichardo (center) receives a plaque from Dodger President Peter O’Malley (right) and Dodger Vice President Tommy Lasorda (left) on the 10th Anniversary of Campo Las Palmas, the Dodgers’ baseball academy in the Dominican Republic.

According to DiarioLibre.com, upon his passing, “Pichardo was in his time one of the Dominican baseball executives with the greatest international projection. His relationships with Peter O'Malley, Al Campanis, Tom Lasorda and Rafael Avila made the Los Angeles Dodgers the organization that supplied the Licey (Tigres) with the best players.” DiarioLibre.com, April 19, 2006 Pichardo joined the Licey club in 1954 and took over as President and General Manager in 1963-64. The O’Malley family invited Pichardo to visit Dodgertown, their longtime spring training camp, every year as its guest.

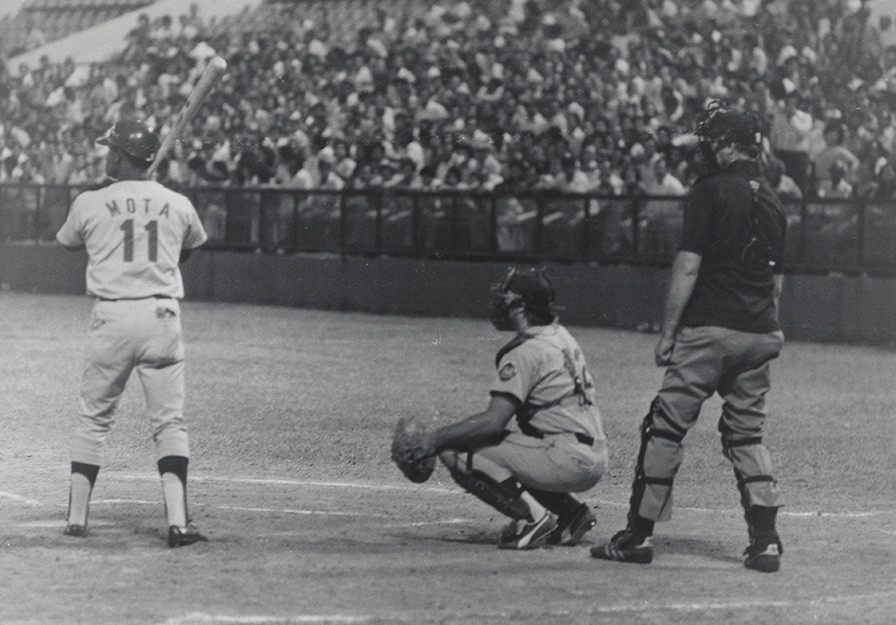

In 1977, the Dodgers and the New York Mets became the first two Major League Baseball teams to play exhibition games in the Dominican Republic, as they staged a two-game exhibition series in Santo Domingo. On March 19, the Dodgers defeated the Mets, 5-3, in 12 innings before 14,000 enthusiastic baseball fans at Estadio Cibao in Santiago. The next day, March 20, another 14,000 fans were on hand at Estadio Quisqueya and an international TV audience, as the Dodgers shut out the Mets, 4-0. Joseph Durso, Special to the New York Times, March 21, 1977

Santo Domingo native Manny Mota, Dodger pinch-hitter extraordinaire, was the hero on March 20, 1977 when the Dodgers played the New York Mets in the Dominican Republic when he hit a pinch-hit home run off Tom Seaver. The Dodgers and Mets were the first two teams to play exhibition games in the Dominican. Mota is batting for the Dodgers and John Stearns catching for the Mets.

But the real excitement came as local hero Mota gave Dominican fans plenty to shout about when he came to home plate and coolly belted a two-run, pinch-hit home run off Mets’ ace Tom Seaver in the fifth inning. Hall of Famer Seaver was stunned, as Mota had only hit one home run in five years. And, Mota would only hit one more home run in the last five seasons of his major league career.

“I’ll never forget that because it was one of the greatest feelings I ever had as a pinch-hitter, coming in front of my home people,” said Mota. “The fans went wild and I can’t describe just how I felt to come through in front of the fans all over Latin America, the Dominican Republic and in L.A.” Rory Costello, SABR.org, “Manny Mota” biography, December 2018

By the early 1980s, in addition to the Pirates and the San Francisco Giants, the Toronto Blue Jays and the Dodgers were very interested in finding talent in the Dominican. For young players who had a passion for baseball, having a major league scout consider you one of the island’s best was a way to emerge out of rampant poverty and the opportunity to provide for a family’s needs. A country largely dependent on sugar, in the 1970s and 1980s mining and tourism began to develop as sources of economic growth. Countrystudies.us/Dominican-Republic

According to The Sporting News in 1983, “The Blue Jays, following in the Dodgers’ footsteps, have become the second team to build a year-round complex in the Dominican Republic. It is partly for unsigned kids (mostly in the 15-16 age bracket) the Jays are interested in, partly for young players who report in June to Bradenton, Fla., and, in the off-season, it’s available for any Toronto player under contract. There is a dormitory that houses 15-30 youngsters, and intrasquad games are played daily at the complex…” Peter Gammons, The Sporting News, March 7, 1983

The Dodgers had fields and were looking at players at tryout sessions like a handful of other teams in the majors, but the full-fledged scouting of the Dominican was just in the early innings. Avila was heavily involved in starting the Dominican Summer League in 1984, which had four cooperative teams, as major league clubs continued their search for elite players. Cesar Brioso, South Florida Sun Sentinel, “Major League Beisbol”, July 30, 2000

“We got the idea, and then Philadelphia and Toronto were jumping ahead of us,” Avila said in a 2000 interview. “We were working in San Pedro de Macoris but not with all the facilities we needed. When (then-Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley) saw that the idea was working good for other organizations, he said, ‘OK, we’re going to go now and do something better than everybody else.’ That’s when we came up with Campo Las Palmas.” Ibid.

At one of the Dodgers’ tryout camps in the Dominican, Avila spotted a sprouting bean pole with arms. It was a thin 15-year-old named Ramon Martinez. He had obvious raw talent according to Avila, but the scout was concerned about Martinez’ weight at about 135 pounds. Of course, Martinez was still maturing into what would eventually be a 6-foot-4 frame, but he just needed to eat more nutritious food and a lot of it.

(L-R): Dodger Manager Tommy Lasorda; Dodger Vice President, Campo Las Palmas Ralph Avila; Dodger pitcher Ramon Martinez; Hall of Fame Dodger Spanish-language broadcaster Jaime Jarrin; and Dodger President Peter O’Malley. On July 14, 1995, it was a jubilant evening for the Dodgers as pitcher Ramon Martinez, center, threw a 7-0 no-hitter against the Florida Marlins at Dodger Stadium. The group celebrates the achievement in Lasorda’s office in the clubhouse.

After a year of working out with the Dodgers, Martinez at 16 became the youngest player on the Dominican Republic Olympic Baseball team and one of the youngest competitors in the 1984 Games of the XXIII Olympiad in Los Angeles. Baseball was played at Dodger Stadium in an eight-team exhibition tournament, the largest involvement for the sport at the time. Dodger President O’Malley worked closely with the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee to host the tournament as one of two demonstration sports. Upon his return from the Olympics, Martinez was signed as an amateur free agent by the Dodgers on September 1, 1984 by scouts Avila and Eleodoro Arias. In 1985, Martinez would return to the United States to play rookie ball for the Dodgers on the Bradenton, Florida team in the Gulf Coast League.

By 1986, Avila, Campanis and O’Malley were in agreement that a state-of-the-art baseball academy would be a better way to hunt for talent and the need for intensive training and development. O’Malley was prepared to privately build it, if he and Avila could identify a parcel of land that could be used for such a purpose. They searched several sites including San Pedro de Macoris, Boca Chica and Villa Mella. Once Avila and O’Malley found the location in Guerra, about an hour’s drive from Santo Domingo, O’Malley had Santiago Fernandez, Dodger team attorney, negotiate and prepare the land agreement. O’Malley was willing to make the initial investment of about $400,000 to privately build and establish the academy. Bill Plaschke, Los Angeles Times, February 12, 1991 O’Malley was hands-on in the process, traveling to the Dominican Republic twice in 1986 and again in January, 1987 prior to the opening of the academy.

Campo Las Palmas, as the academy was to be known, sat on nearly 50 acres of farm land with pastures developed for baseball fields, a clubhouse, a dormitory with wooden bunk beds, kitchen, dining and meeting rooms. Lush tropical landscaping and well-manicured fields would enhance the beauty of the unique baseball locale. It was all created and designed by Avila and O’Malley for young prospects who were discovered on the island, then brought to the camp for a closer look and eventually signed or not.

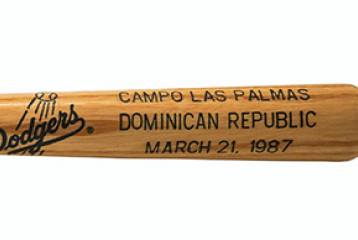

On March 21, 1987, O’Malley led a Dodger delegation from Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida to dedicate Campo Las Palmas. That group included Executive Vice President Fred Claire, Manager Tommy Lasorda, Coach Manny Mota, Spanish-language broadcaster Jaime Jarrin, and Dominican players: first baseman Pedro Guerrero of San Pedro de Macoris, infielder Mariano Duncan of San Pedro de Macoris and pitcher Alejandro Peña of Cambiaso, Puerto Plata.

(L-R): Seated, Dodger Manager Tommy Lasorda; Standing, Dodger President Peter O’Malley; Dodger Pedro Guerrero; Dodger Spanish-language broadcaster Jaime Jarrin; Seated, former Dodger and actor Chuck Connors. On March 20, 1987, a Dodger delegation is flying to the Dominican Republic for the dedication of Campo Las Palmas, the Dodgers’ state-of-the-art baseball academy.

They were joined by former Dodger Chuck Connors, a television and film actor, who had trained with the 1948 major league Dodgers in the Dominican. Connors is best known as the star of the long-running TV series “The Rifleman.” Though he did not make the 1948 big league roster, he did play one game for the Dodgers on May 1, 1949. Connors finished his brief major league career with the Chicago Cubs in 1951. A fine athlete, Connors is in an elite group that also played in the NBA.

March 21, 1987, Opening Ceremonies, Campo Las Palmas baseball academy, Guerra, Dominican Republic. (L-R): Center only – U.S. Ambassador Lowell Kilday; Dominican Republic Minister of Sports Andres Van de Horst; Dominican Republic Vice President Carlos Morales Troncoso throwing ceremonial first pitch; Dodger President Peter O’Malley; Dodger Executive Vice President Fred Claire; and Miguel Hernandez.

Special mini bats were created by Dodger President Peter O’Malley for the March 21, 1987 dedication of Campo Las Palmas, Guerra, Dominican Republic.

U.S. Ambassador to the Dominican Republic Lowell Kilday (left) is with Dodger President Peter O’Malley for the March 21, 1987 dedication ceremonies of Campo Las Palmas, the Dodgers’ state-of-the-art baseball academy in the Dominican Republic. The dedication bronze plaque is behind Ambassador Kilday and O’Malley.

The Vice President of the Dominican Republic Carlos Morales Troncoso arrived via helicopter to participate in the opening ceremonies. Lowell C. Kilday, U.S. Ambassador to the Dominican Republic, also attended and was part of the festivities to open the camp. As a career foreign service officer, Kilday had been appointed by President Ronald Reagan to the Dominican in 1985.

Campo Las Palmas, the Dodgers’ state-of-the-art baseball academy, opened March 21, 1987 created, designed and developed by Ralph Avila and Peter O’Malley. Nearly 40 years later, Campo Las Palmas continues to give aspiring Dominican players an opportunity to go to the United States and play Major League Baseball.

Other clubs took notice of the Dodgers’ extraordinary new complex, complete with its own water supply, electricity and fuel. Those were important island commodities which resulted in the smooth operation of the campus. There were three baseball fields, along with batting cages and pitching machines. Players would spend long days on the fields for instruction and training. An on-site kitchen prepared meals for the players to enjoy. Campo produced some of its own garden and farm grown food like sugar cane, while roosters, chickens and pigs wandered the premises. The main reason Campo exists is for the development of talent and a way for a young player to fulfill his dream of playing baseball in the United States, challenging the best of the best in the game.

While attending a squad game at Campo Las Palmas in July, 1987, Hall of Famer and former Dodger pitcher Juan Marichal said, “There is nothing like it in all of the Caribbean.” Rob Ruck, University of Pittsburgh, latinousa.org, originally from The Conversation, “The Promise and Peril of the Dominican Baseball Pipeline”, March 25, 2019

March 21, 1987, Opening Ceremonies, Campo Las Palmas baseball academy, Guerra, Dominican Republic. (L-R): Gloria Avila, wife of Ralph Avila, Dodger Latin America scout and Director, Campo Las Palmas Ralph Avila, and Dodger President Peter O’Malley with dedication plaque.

Avila, originally from Cuba, was in charge, playing multiple roles on site from Campo director to Dutch uncle, taking each player under his wing to try to help him grow. For sure, he was an effective scout, but he would also have to train talent in the Dodger way of playing baseball. He helped to coach players and provide tips to make them better. Of course, at times Avila would have to comfort and encourage players who were away from home at a young age in a competitive environment. At the same time, a large portion of time off the fields was established to teach English to players. This proved important, so that words and phrases were understood in order to make the transition to baseball life in the United States.

A player might be signed by the Dodgers and then be sent to a rookie or Single-A team in Great Falls, Montana; Vero Beach, Florida; or Bakersfield, California, a far cry from home. As the Dodgers saw it, he had to be prepared and given the proper tools and training at Campo. How to assimilate into United States culture would be just as important as how to hit or throw a curveball. Baseball skills, nutrition, English and character all were taught by Avila, his coaching and support staff, and teachers from the local high school. Recreation space was provided for the players to unwind and relax.

On-site housing was available initially for some 60 players. Portions of the camp were named for famous Dodgers, including the Walter O’Malley headquarters, Tom Lasorda dining room, the Roy Campanella clubhouse, the Al Campanis classroom and Manny Mota Field. O’Malley and Avila brought in a satellite to beam in television and also established a relationship to be good neighbors with Futuro Vivo, a school run by Carmelite sisters in Guerra.

On April 12, 1994, Dodger Vice President, Campo Las Palmas Ralph Avila (left) and Dodger President Peter O’Malley are at Campo Las Palmas baseball academy in Guerra, Dominican Republic. Avila and O’Malley created Campo Las Palmas, which opened on March 21, 1987, as a training grounds for aspiring Dominican baseball players.

It was Avila’s idea to become involved with Futuro Vivo in 1987, as two Sisters from Spain (Inés de Mercado and María Cristina de Jesús) had just started it and were offering free education, books, transportation, nutrition and medical care to a handful of underprivileged students. O’Malley agreed and through their efforts and the Dodgers’ help, the school continued to expand and thrive over the years to help hundreds of disadvantaged children from kindergarten to eighth grade. With on-going support by O’Malley, a chapel was built. The friendship started by Avila and O’Malley with Futuro Vivo has continued for more than three decades.

In the winter of 1988, at the suggestion of Dodger Manager Tommy Lasorda, 20-year-old catcher and 62nd round Dodger draft pick Mike Piazza expressed a desire and willingness to go to Campo Las Palmas. Piazza would receive extra instruction to hone his skills behind the plate and as a hitter, as well as learn to effectively communicate with Spanish-speaking pitchers. Previously, no other American-born player had gone to Campo to improve his game. J.P. Hoornstra, Los Angeles Daily News, July 23, 2016 That commitment may have been a turning point in Piazza’s Hall of Fame career.

The Dodgers’ quest for talent at the Dominican camp played an essential role in formulating the rosters of their teams in the 1990s. The pipeline that the Dodger brass had hoped for was reaping benefits. O’Malley named Avila a Dodger Vice President on December 12, 1991.

A view of the instructional and playing fields, plus four buildings comprising the Dodgers’ Campo Las Palmas baseball academy, circa 1993.

Players who emerged from development at Campo Las Palmas and played for the Dodgers include: infielder Jose Vizcaino, who first played for the Dodgers in 1989; shortstop Jose Offerman who had played just two minor league seasons before his 1990 call-up -- he became a 1995 National League All-Star; Pedro Astacio, who first pitched for the Dodgers on July 3, 1992; outfielder Henry Rodriguez, who got in his first game on July 5, 1992; Hall of Fame pitcher Pedro Martinez, who debuted on September 24, 1992; right fielder Raul Mondesi, who first played for the Dodgers in 1993 and became National League Rookie of the Year in 1994; Wilton Guerrero, second baseman who debuted on September 3, 1996; and third baseman Adrian Beltre, who made his debut with the Dodgers in 1998 and completed a Hall of Fame career with 3,166 hits 20 years later.

“We look at everybody, and we will keep looking at everybody, because you just never know,” said Pablo Peguero, who has been by Avila’s side running Campo Las Palmas and holds regular tryout camps. “The talent in this country could be anywhere.” Ibid.

O’Malley was in Santo Domingo for the induction of Avila into the Dominican All-Sports Hall of Fame at the renowned Hotel Jaragua on October 20, 1996. O’Malley met with Leonel Fernandez, President of the Dominican Republic, on October 21 at the Presidential Palace.

On October 21, 1996, Dodger President Peter O’Malley meets with Leonel Fernandez, the 50th President of the Dominican Republic, in Santo Domingo. Induction ceremonies of Dodger Vice President, Campo Las Palmas Ralph Avila to the Dominican Republic All-Sports Hall of Fame were held October 20, 1996. Fernandez served as Dominican Republic President from 1996-2000 and again from 2004-2012.

On March 22, 1997, Campo Las Palmas 10th Anniversary celebration, Guerra, Dominican Republic. Participating in ribbon cutting ceremonies are (L-R): Dodger President Peter O’Malley; Hall of Fame pitcher and Dominican Republic Minister of Sports Juan Marichal; Dodger Vice President, Campo Las Palmas Ralph Avila; Dodger Vice President and Hall of Fame Manager Tommy Lasorda. Behind in center is Dodger Executive Vice President Fred Claire.

On March 22, 1997, O’Malley traveled to Campo Las Palmas with pitchers Ramon Martinez and Pedro Astacio to celebrate the 10th Anniversary of the academy with ceremonies on the main baseball field. On February 7, 1998, O’Malley returned to the Dominican for ceremonies to honor famous Dodger alumni from Campo Las Palmas including Pedro and Ramon Martinez, Pedro Astacio, and Raul Mondesi.

(L-R): Peter O’Malley; Hall of Fame pitcher Pedro Martinez; Raul Mondesi; Dodger Vice President, Campo Las Palmas Ralph Avila; Pedro Astacio; Hall of Fame Dodger Manager Tommy Lasorda; and Ramon Martinez. On February 7, 1998 a ceremony to celebrate famous alumni of Campo Las Palmas is held at the famous baseball academy in Guerra, Dominican Republic.

On February 7, 1998, pitcher Pedro Martinez (left) is with Dodger President Peter O’Malley at Campo Las Palmas, Guerra, Dominican Republic, for ceremonies to honor famous Dodger alumni. Martinez was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2015.

Henry Rodriguez, who played for the Dodgers from 1992-1995 and a total of 11 years in the majors, said of Campo Las Palmas, “They had the best coaches and the best facility in the Dominican Republic. You learned because of the kind of coaches they had and the way they taught you. They wanted you to learn. It was a very nice thing to go through the academy because we learned a lot.” Cesar Brioso, South Florida Sun Sentinel, “Major League Beisbol”, July 30, 2000

Former Dodger General Manager Ned Colletti wrote, “Dodger owner Peter O’Malley and general manager Al Campanis were visionaries. Like Peter’s father, Walter O’Malley, who saw the benefits of moving to the West Coast and expanding the scope of baseball, Peter and Al had the same type of vision that led this organization to the Dominican Republic. This would be the place the Dodgers could find, sign and develop players to help our big league club. Ralph Avila was the man they tabbed with the job…He was passionate about both baseball and Latin America, and married the two when he found an organization in which he could be trail blazer. The organization had the foresight to believe in the area and believe in Ralph, and believe in changing a dynamic where an organization built a complex and gave young players a chance to play and end up in the big leagues.

“To understand the importance of Campo Las Palmas, consider how hard it is to get a player the caliber of Pedro Martinez or (Raul) Mondesi or (Adrian) Beltre. To find a player that good in the amateur draft, you would probably have to be picking in the top 10, but the Dodgers were so good during that era they rarely had picks that high. Furthermore, with the draft you have to hope nobody picks the specific players you have your eyes on. But with Campo Las Palmas, the Dodgers could find, scout, sign and develop those players from a young age.” Ned Colletti, “Dodgers’ Latin America legacy still strong”, SportsNetLA.com, June 17, 2015

O’Malley invited the Sinon Bulls of the Chinese Professional Baseball League in Taiwan to train at Campo Las Palmas in the spring of 1997. Sinon became the first team from Taiwan to train in Latin America when they visited Campo Las Palmas. The Bulls trained intensively for 40 days, 10 hours per day. In 1998, the Bulls returned to Campo and the Sinon owner and team president T.F. Yang stayed in accommodations at the camp with his team for five days.

Dodger Vice President, Campo Las Palmas (left) presents Dodger President Peter O’Malley with a framed ceramic tile tribute for his contribution to creating, developing and financing state-of-the-art Campo Las Palmas baseball academy for the Dodgers in 1987. O’Malley was at Campo Las Palmas in the Dominican Republic from September 3-6, 1999.

On May 29, 2010, Peter O’Malley was inducted into the inaugural class of the Latino Baseball Hall of Fame at the Roman Amphitheater, Altos de Chavon in La Romana, Dominican Republic. The organization recognized O’Malley for making “great contributions to Latino baseball.”

On February 9, 2013, longtime Dodger player and major league coach Manny Mota dedicated one of his International Foundation’s fields in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic “Estadio Familia O’Malley” or “The O’Malley Family Baseball Stadium” in honor of the O’Malley family “for your great contributions to the game of baseball, your friendship and your long term support of our philanthropic endeavors.”

According to Mota, Dominican Republic President Leonel Fernandez and several Dominican-born major league players were in attendance for the dedication and first pitch ceremonies. Parachute jumpers from the Dominican Republic Air Force performed. President Fernandez provided for the construction of the stadium.

The main stadium is still used primarily by 14-16 year olds and some adults in the Manny Mota League. Games are played on Saturdays and Sundays and practices are on Wednesdays. The stadium’s dimensions are 320’ down the lines and 388’ to center field. Young players, ages 6-8, and 10-12, are on one of three other baseball fields. Youngsters at the Manny Mota International Foundation complex receive education and baseball tools and as Mota says “keep kids away from temptations and off the streets.”

“The O’Malley family deserves the recognition because of all the contributions to baseball and education in the country,“ said Mota. “We are very grateful.”

Estadio Familia O’Malley, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic was dedicated on February 9, 2013 to the O’Malley Family in recognition of its “contributions to baseball and education in the country.”

On February 9, 2013, the Manny Mota International Foundation named its primary baseball stadium “Estadio Familia O’Malley” in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. The stadium is used primarily for games by 14-16 year olds and by adults in the Manny Mota League.

Campo Las Palmas is still a valuable part of the Dominican baseball scene. As of the 2025 season, 100 players on the major league Opening Day rosters were from the Dominican Republic, which led the list of countries with non U.S.-born players.