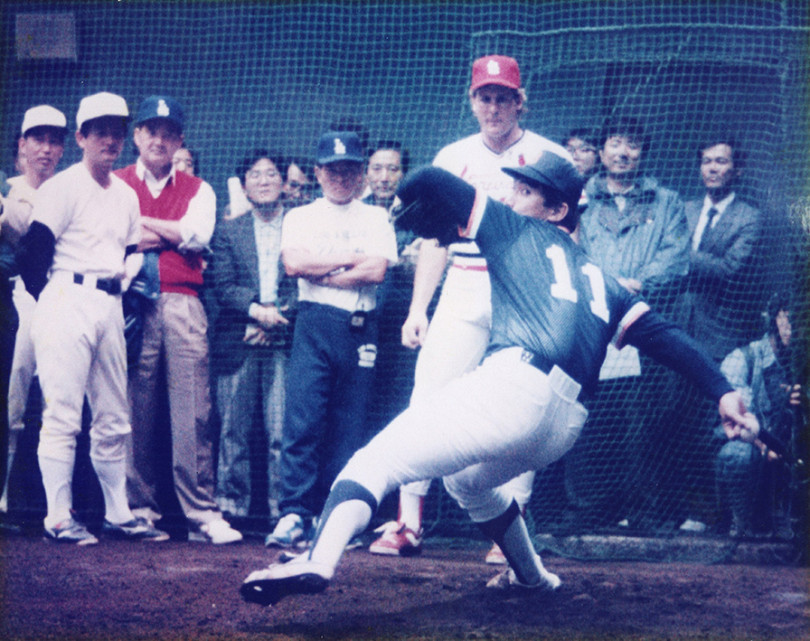

Hideo Nomo (No. 11) is pitching at the 1988 US – Japan Baseball Summit at Tokyo Dome which started November 22. Dodger Assistant to the President Akihiro “Ike” Ikuhara (center with Dodgers cap) watches Nomo along with other baseball officials, including Shigeo Nagashima, Japan Baseball Hall of Fame third baseman of the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants who is wearing a red sweater vest. In 1990 at age 21, Nomo signed with Kintetsu in Nippon Professional Baseball.

Courageous Warrior Hideo Nomo Made the Ultimate Leap to Change Baseball

By Brent Shyer

The year 1995 will be remembered for many big news stories: the murder trial of O.J. Simpson; the assassination of Israel Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin; and the bombing of the Oklahoma City Federal Building. But, in the world of sports nothing was more important to baseball and its future in two countries than the Dodgers’ signing of right-handed pitcher Hideo Nomo of Japan.

It took the O’Malley family decades of goodwill, friendships and exchanges with Japan to get to that key moment.

Only one Japan-born player had ever come to America to play in the major leagues. In 1964, the Nankai Hawks’ left-handed pitcher Masanori Murakami, 19, catcher Hiroshi Takahashi, and third baseman Tatsuhiko Tanaka, both 18, were sent to the San Francisco Giants’ minor league system to further their development. Murakami was at Single-A Fresno as an “exchange student,” supposedly for a short period of time. But, Nankai failed to summon him back to Japan during the season and when the Giants’ bullpen ran thin late in their schedule, they promoted Murakami and he made his major league debut then at 20 years old.

That caused a commotion in the off-season between Nankai, professional baseball in Japan, the Giants and Major League Baseball. Nankai sought Murakami’s immediate return to Japan and the Giants wanted him to stay. A compromise was struck so that Murakami would play one additional full season and then return to Nankai. He did go back to the Hawks in 1966 and played for another 17 years.

From that time until 1995, no other Japan-born player participated in Major League Baseball, as rules were established by the governing bodies’ “gentleman’s agreement” to prevent that.

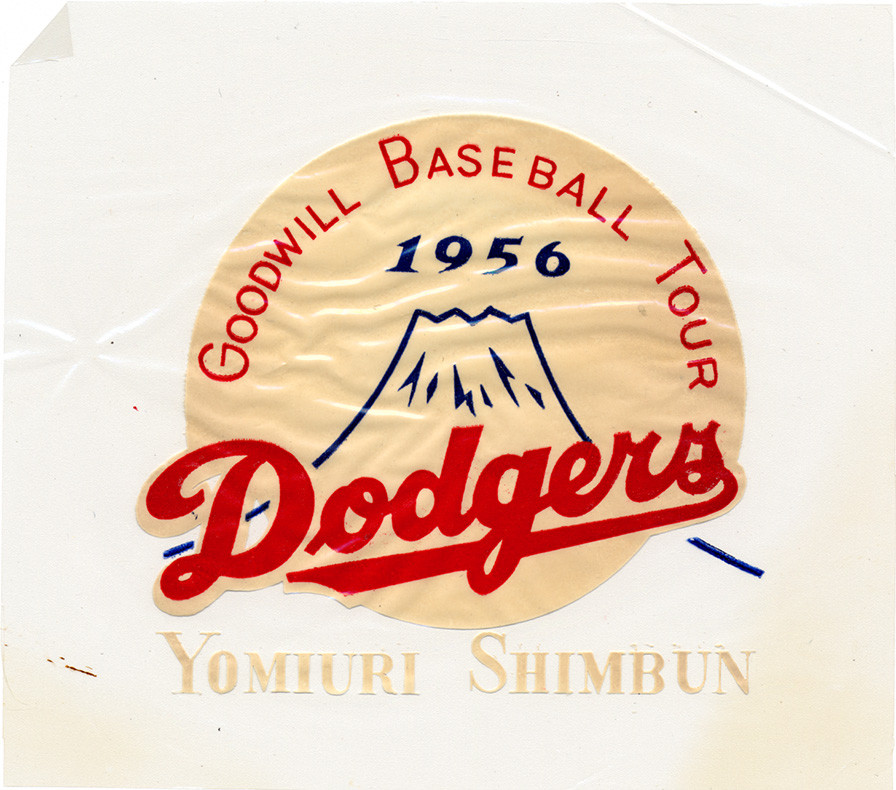

The O’Malley family began its longtime ties with Japan in 1956. That was the year that Matsutaro Shoriki, the founder of the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants, owner of the widely-circulated Yomiuri Shimbun and the “father of professional baseball in Japan,” wanted to invite the Dodgers to play exhibition games throughout Japan in the fall. For that purpose, Shoriki sent his confidant Sotaro Suzuki, a famous Yomiuri sports advisor and a baseball ambassador to America to meet with Dodger President Walter O’Malley in New York. A friendship between O’Malley and Suzuki started as the details and arrangements for the 1956 Dodgers Goodwill Tour to Japan were unfolding.

A welcoming ceremony for the Dodgers during their 1956 Goodwill Tour to Japan. (L-R): pitcher Carl Erskine; Japan Baseball Hall of Fame columnist Sotaro Suzuki; Walter O’Malley; Tokyo Yomiuri Giants owner Matsutaro Shoriki; National League President Warren Giles; Dodger Director of Scouting Al Campanis; and outfielder Don Demeter.

Once agreed by O’Malley and the Dodgers, he took his wife Kay, daughter Terry and son Peter on the month-long Goodwill Tour to Japan. It was an eye-opener for 18-year-old Peter, who very much enjoyed making new friends and seeing how baseball was a way of bringing divergent cultures together, especially since this was only a decade in the aftermath of the devastation of World War II. The fans at the stadiums in Japan were knowledgeable about baseball, welcoming, and thoroughly enjoyed watching the Dodgers play. Their major stars like Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Gil Hodges, Carl Erskine and a young Don Drysdale were all on the trip to play the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants and other teams comprised of All-Stars from Japan’s two professional leagues.

This unique red ink Dodger logo cellophane is from the 1956 Dodgers Goodwill Tour to Japan, showcasing Mt. Fuji in the background. The tour was sponsored by the Yomiuri Shimbun.

The friendships continued just months later, as Walter O’Malley invited Suzuki, Tokyo Yomiuri Giants Hall of Fame Manager Shigeru Mizuhara and two Giants players – pitcher Sho Horiuchi and catcher Shigeru Fujio – to Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida during 1957 Spring Training. That solidified the relationship and led to more exchanges in succeeding years, including the first team visit by the Giants to Dodgertown in 1961. The Giants were the first team to visit a major league team in spring training.

Dodgertown became a critically important centerpiece for much of what transpired internationally in the decades ahead. The Giants were appreciative of the opportunity to train along with the Dodgers at Dodgertown and learned more about training techniques and game strategy during their lengthy workouts. Having the same advantage as the Dodgers to stay on base at Dodgertown where they dined together, slept in the old U.S. Naval barracks on site for their first three visits and used the recreational spaces, it bonded the team together at the most important time of the year.

In the five times the Giants were on site preparing for their seasons in 1961, 1967, 1971, 1975 and 1981, they went on to capture the Japan Series Championship on four occasions. Peter O’Malley was responsible for all arrangements, including schedules and sightseeing for the 1961 Giants team visit from their arrival to departure. He got to know two of Japan’s all-time greatest baseball players – Sadaharu Oh and Shigeo Nagashima. Since connecting with them at Dodgertown, these friendships have lasted more than 60 years.

In 1964 and 1965, Walter O’Malley was happy to fulfill a Tokyo Yomiuri Giants’ request and send top scouts Al Campanis, Tommy Lasorda and Kenny Myers to Tokyo and Miyazaki, home of the Giants’ spring training, to instruct the team. Lasorda would later manage 20 seasons for the O’Malley family and was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame with two World Championships.

One of the game changers occurred when Akihiro “Ike” Ikuhara joined the Dodger front office. A former baseball player at Waseda University, Tokyo for respected Coach Renzo Ishii, Ikuhara himself coached baseball at Asia University before coming to America in 1965. Suzuki sent a letter introducing Ikuhara to Walter O’Malley and asked if the Dodgers would be interested in having Ikuhara learn the business side of baseball, while helping the front office. O’Malley agreed and it was the start of a 27-year friendship with Ikuhara and the Dodgers. Initially, Ikuhara assisted Peter O’Malley in Spokane, Washington at the Dodgers’ Triple-A farm team, but he followed Peter to Dodger Stadium in 1967 when Peter was named Vice President, Stadium Operations.

The Dodgers were invited to return to Japan for the 1966 Goodwill Tour and played a 19-game schedule following their regular season. Ikuhara played a prominent role in the 1966 tour assisting the Dodger traveling party and the interactions with Yomiuri. Once again, their hosts expressed great appreciation for the visit of the Dodgers, managed for the second time by Hall of Famer Walter Alston.

Because of Peter’s interest in furthering the growth of baseball worldwide, he regularly had Ikuhara by his side for important meetings at Dodger Stadium – Los Angeles, in Japan, and many other countries where they traveled together. They were key advocates for baseball to be included in the Olympic Games as a gold medal sport. For years, Dr. Bob Smith, President of the International Baseball Association, Major League Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, O’Malley, Ikuhara and Rod Dedeaux, legendary head baseball coach at the University of Southern California, carried that torch through international baseball meetings, correspondence, phone calls, personal visits with international baseball leaders, and governmental representatives to achieve that goal by earning IOC voter support.

In the meantime, O’Malley financially guaranteed the eight-team exhibition tournament of baseball at Dodger Stadium as a demonstration sport in the 1984 Games of the XXIII Olympiad in Los Angeles. Japan won the championship over the USA team, 6-3, before a sold out crowd. Attendance for baseball was the third highest among all events. That was meaningful, as it showed the growth of Japan’s baseball youth programs were producing great talent for Nippon Professional Baseball. Sixteen players on Team Japan went on to play professionally in Japan.

Peter, as his dad Walter before him, invested time and assistance to many in Japan. In 1969, Toru Shoriki succeeded his father Matsutaro as owner of the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants. He and Peter O’Malley worked together on several projects. Shoriki frequently traveled to Los Angeles to meet with O’Malley. In 1967, O’Malley traveled with Toru Shoriki through several Pacific Coast League baseball team operations including Spokane to give him a clear view of the top minor league system. Besides the visits to Dodgertown, O’Malley and Shoriki established a “friendly agreement” in Tokyo for more coaching and player exchanges in 1980. The Giants sent three rookie players and a minor league batting coach to Dodgertown that spring. O’Malley spent time with Shoriki discussing a plan to advance baseball to gold medal status in the Olympic Games.

O’Malley also maintained excellent rapport with other baseball leaders in Japan. In 1987, arrangements were made for two professional Chunichi Dragons rookies to play for the Sarasota Dodgers. In Spring Training, 1988, the entire Chunichi team, managed by Japan Baseball Hall of Famer Senichi Hoshino, was invited by O’Malley to train at Dodgertown for two and a half weeks alongside the major league Dodgers. In 1989, pitchers from the Dragons were permitted to pitch for Single-A Vero Beach and Rookie Kissimmee Dodgers minor league teams.

Then in 1995, the opportunity was presented to sign free agent Hideo Nomo, who had pitched for the Kintetsu Buffaloes for five seasons and had 78 wins. Nomo’s agent Don Nomura discovered a loophole in the Japanese Uniform Players Contract for Nippon Professional Baseball. It eventually allowed Nomo to “retire” voluntarily. A retired player, should he decide to be reactivated, could only do so for his former club in Japan. But as far as using the loophole, the player could retire and then become a free agent to play in the United States. It was a stunning development.

O’Malley did his homework with many longtime friends, including two legendary Japan Baseball Hall of Famers – Sadaharu Oh, baseball’s world recordholder for home runs with 868, and Shigeo Nagashima, third baseman who, like Oh, played for 11 Japan Series Champions. O’Malley also called good friend Coach Ishii of Waseda to learn anything about Nomo. He found out a lot: a Nippon Professional Baseball record eight teams drafted Nomo in the first round. Kintetsu was the lottery winner and signed him. Nomo won 1990 Pacific League Rookie of the Year honors, as well as the Sawamura Award for pitching (equivalent to the Cy Young Award in the majors) and league MVP. No other player had achieved that in one season. Nomo led the Pacific League in strikeouts four consecutive seasons (1990-1993).

He learned Nomo was confident, had always been studious. Nomo’s father Shizuo, who was a fisherman and postal service worker, started playing baseball with him when Hideo was five. Bill Staples, Jr., SABR Bio Project, Hideo Nomo Robert Whiting, JapaneseBaseball.com, “Contract loophole opened door for Nomo’s jump,” October 10, 2010 Shizuo and his wife Kayoko gave Nomo the name Hideo, which the Japanese translate as “hero”. Little did they know by age 12, Nomo would dream of playing baseball professionally. He would eventually let his pitching do the talking for him in two countries.

All the information coming from Japan about Nomo was positive.

“Our scouts had…minimal reports on him,” O’Malley said. “But friends in Japan, friends in baseball (professional baseball, amateur baseball), they all said, ‘He’s the right guy. He’s tough, he’s strong, he wants to do it, and he’ll do it well.’ So it was more on the personal recommendation of baseball people than a professional scout.” Jason Coskrey, Japan Times, “Former Dodgers owner reflects on Nomo, friendships”, July 2, 2013

Then Dodger Executive Vice President and General Manager Fred Claire recalled in a 2020 interview, “I was very, very impressed with Hideo, both from what I had heard about him as a pitcher and looking at his record in Japan. More important, just meeting him and talking to him through Don (Nomura) to get a sense of who he was and what his objectives were or his reasoning was in wanting to sign with a major league team.” Ed Odeven, Japan-forward.com, August 22, 2020

O’Malley said, “He (Nomo) came to my office on his way to Atlanta and New York. He wanted to see (George) Steinbrenner (owner of the Yankees) and (Ted) Turner (chairman of the Braves). I told him we really wanted him here. This was the best place for him, and we would take good care of him.” Gordon Edes, Boston Globe, April 5, 2007

O’Malley continued, “When I met Hideo at my office, it did not take me long to understand what my friends in Japan had told me was spot on. I remember feeling the professionalism, the responsibility and the dedication just flowing out from him. He had the three attributes that I respect the most. With that being said, I told myself that I was not going to let him out of the office at least until he felt the sincerity from us.” Brad Lefton, Sports Graphic Number 1009, Hideo Nomo Special, “The Impact Nomo made to the MLB” Nomo and Nomura cancelled their trip.

Bob Nightengale wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “O’Malley is responsible for Nomo being a Dodger. He eagerly waited for Major League Baseball to give permission for U.S. teams to negotiate with Nomo after the pitcher declared free agency in Japan. The Dodgers telephoned the day permission was given. They wanted for Nomo to visit the Dodgers first, but instead he visited the Seattle Mariners and San Francisco Giants, making Los Angeles a third stop.” Bob Nightengale, Los Angeles Times, July 4, 1995

A happy occasion as Dodger President Peter O’Malley shares a smile with pitcher Hideo Nomo on the stage for Nomo’s introductory press conference on February 13, 1995 at the New Otani Hotel in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles.

At his introductory press conference on February 13, 1995 after signing a minor league contract with the Dodgers, Nomo said he chose the Dodgers for one main reason. “The (Seattle) Mariners and the (San Francisco) Giants did not have a Peter O’Malley.” Rafu Shimpo, February 14, 1995

O’Malley told the press, “It’s a happy, happy day. Everybody’s dream is fulfilled. His dream, our dream. I said to myself, ‘Someday, we’ll have a player who played professionally in Japan play in the major leagues.’…We’re definitely getting closer to the day for a true World Series. That’s been our dream for a long time. This exchange helps us get closer to the day of a true World Series. Lawrence Rocca, Orange County Register, February 14, 1995 I told him if he chose the Dodgers, we would do everything possible to make him comfortable. But he knew a lot about the Dodgers before I ever met him. Our reputation in Asia, I think, helped us.” Ken Daley, Los Angeles Daily News, February 14, 1995

February 13, 1995, the Dodgers are all smiles on the signing of Japan-born right-handed pitcher Hideo Nomo at the press conference to introduce him at the New Otani Hotel in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles. (L-R): Dodger President Peter O’Malley; Nomo; Dodger Executive Vice President and General Manager Fred Claire; and Minor League Director Charlie Blaney.

The news shook baseball to its core. First, because there had only been one other Japan-born player in the Unites States in 30 years.

Second, the media from Japan questioned whether Nomo would be effective against major league hitters and the best competition in the world. They also voiced concern about the “free agency” issue for the future of Nippon Professional Baseball and how other players might attempt the same.

Third, O’Malley and the Dodgers were taking a significant risk by signing a player from a different country and culture, while presenting him with a $2 million bonus. Other clubs were amazed at the size of the bonus and what that would mean for future international signings. But one thing is for sure – baseball fans in two countries were fascinated by Nomo and were curious to see him perform against the best hitters in the game.

For fans in the United States, the Nomo signing came at baseball’s very dark hour of a major league players’ strike and a cancelled World Series in 1994. The strike continued and lingered into 1995 Spring Training. There was “no joy in Mudville” or anywhere else baseball was played at that time. Replacement players were stocked onto rosters and Spring Training went forward, but it was not the same. Until the strike was suspended in April after 232 days and a second Spring Training was held with MLB players, chaos ruled the game.

Baseball was grappling to find a path forward. The answer would come on the broad shoulders of a 26-year-old from Osaka, Japan.

Nomo’s agent Nomura said, “I thought it would be a struggle in the beginning. Peter O’Malley really cared for him (Nomo)…and he wanted Hideo to succeed on the field and off the field. He made sure that (Hideo) was happy with what he was doing, how he was treated, how the environment was for him. So those are very important issues that helped him succeed, and then (perform) well above what he’s done or what people expected of him.” Ed Odeven, japan-forward.com, Second in a Series, July, 2020

Initially, the Dodgers signed Nomo to a minor league contract, as Claire explained to Nomura and Nomo, “I want you to explain to Hideo that major league contracts in the Dodger organization have been earned, and are not given.” Ed Odeven, japan-forward.com, Fourth in a Series, August, 2020

Nomo remembered first going to Dodgertown for Spring Training, hounded by more than 30 media members and photographers from Japan, in addition to the Dodger beat writers fascinated by him: “On the eve prior to the start of Spring Training in March of 1995, I arrived in Dodgertown for the first time. As it was dark, all I could see were the baseball fields and lodging facilities. I thought to myself ‘there is nothing to do here except to play baseball.’

“I did not know how they practiced in the U.S. I did not know anything about the culture and if I might do or say something that might offend people. All of my anxiety and concerns were put to ease by a staff led by my manager, Tommy Lasorda. Everyone would check up on me daily to make sure that I was comfortable and they always asked me if I needed anything. At that time, I could not speak English at all and I did not even know how to greet people, but I could really feel the kindness of everyone around me.

“I arrived at the Dodgers coming off of a shoulder injury. During the month of Spring Training, the staff helped me rehabilitate my shoulder while having a trainer at my side daily. By the end of Spring Training, I was back on the mound pitching to my satisfaction. That experience has become a valuable life lesson for me, as I am now in a position where I am coaching and teaching young players.

“Every day after practice, (Dodger President) Mr. Peter O’Malley would sit down with me and ask how things were going and if everything was OK. Without his kindness, I would have emotionally struggled through Spring Training. I am still so grateful to Mr. O’Malley for the kindness and care that he gave me. I remember at the end of Spring Training, Mr. O’Malley would host a family barbeque party where there was a merry-go-round and animals. It felt like an amusement park. That atmosphere was one that I had never experienced in my life and, most importantly, that was the moment that it felt like the ‘Dodgers’.

“Although I had feelings of anxiety, I am able to look back at the great memories and share them and genuinely say from the bottom of my heart that I am so glad that I chose to become a Dodger.”

1996 Hideo Nomo baseball card by Leaf Studio.

Following the delayed second Spring Training with regular players, the Dodgers initially sent Nomo to their Class-A Bakersfield team. O’Malley watched Nomo’s U.S. professional debut on April 27, 1995 for the Blaze against Rancho Cucamonga. Nomo made such an impression there that on May 2, 1995, he made his major league debut in San Francisco against the Giants at Candlestick Park. There were a lot of early risers in Japan to follow that game as first pitch was at 4:34 a.m.

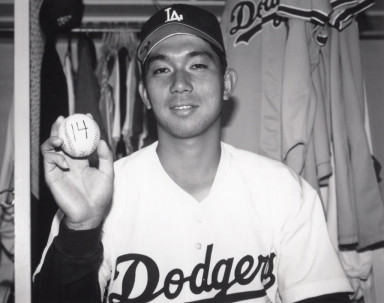

May 17, 1995, Dodger rookie pitcher Hideo Nomo tied the Los Angeles Dodgers record for most strikeouts by a rookie when he fanned 14 batters against Pittsburgh in 7 innings. Photo by Jon SooHoo/Los Angeles Dodgers

From that point, Nomo’s popularity and following only continued to grow. At 6-foot-2, 200 pounds, Nomo used his muscle and skill to go 6-0 in the month of June and, as a rookie, received the rare selection as starting pitcher for the MLB All-Star Game. In 1995, the All-Star Game was played on July 11 in Texas, where all eyes were upon him. In a rather strange development, the other All-Stars could just sit back away from the media spotlight for once and watch “The Nomo Show” in person. In a memorable performance, Nomo went two innings and struck out three, while giving up just one single and no runs. At that stage, the phenomenon known as “Nomomania” had taken off like a missile and the pitcher’s every move was chronicled by the media where he was watched like paparazzi chasing a rock star.

Fans in both Japan and the United States became enthusiastic supporters and were proud of Nomo. Proud because he followed his dream to pitch in the major leagues and proud of how he performed on the field and how he carried himself away from the game.

“I was surrounded by nervousness as if my own son was the starting pitcher,” said O’Malley about Nomo’s performance starting the 1995 All-Star Game. “After Nomo finished pitching and returned to the dugout, I saw everybody congratulating him. I felt relieved and, at the same time, felt warm feelings in my heart that I could not control.” Shuukan Bunshuu magazine, October 26, 1995

Major League Baseball International issued a press release stating a whopping 25 percent of television households in Japan watched the live broadcast of the 1995 All-Star Game. Ken Schanzer, President and CEO of The Baseball Network said, “These spectacular ratings underscore the popularity of MLB and Hideo Nomo in Japan. And they don’t even take into account the tens of thousands of fans who arrived late for work because they watched the game on large-screen TVs located throughout the country.” Major League Baseball International Press Release, July 19, 1995

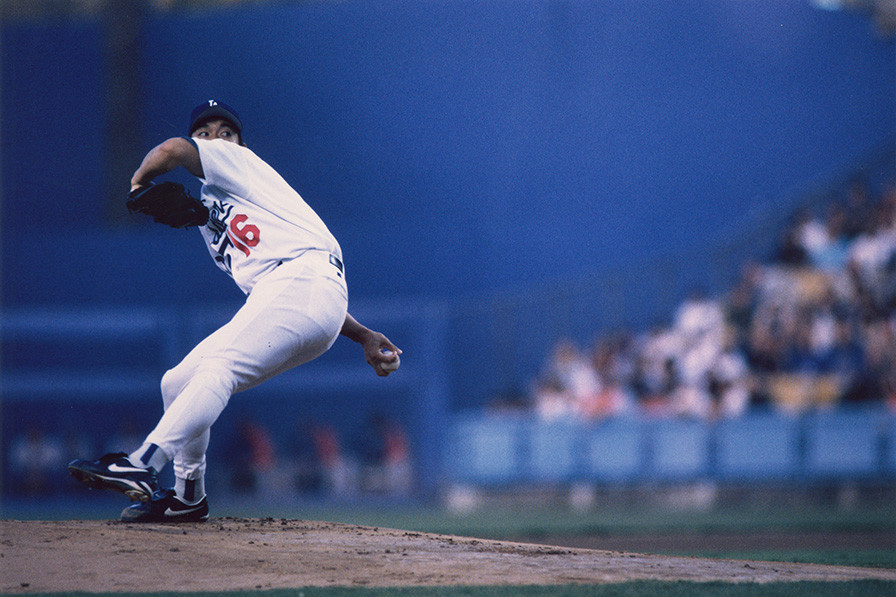

Hideo Nomo on the mound at Dodger Stadium. Known as “Warrior”, Nomo had a twisting and turning delivery style that made it difficult for hitters to pick up the baseball. He was the first Japan-born player to make the major leagues in 30 years and the only one to complete his career in America. Nomo played seven seasons for the Dodgers, winning 81 games out of his MLB career total of 123.

Every single game Nomo pitched was televised live to Japan, no matter the start time. Large video screens were installed on street corners in 13 major cities throughout Japan, so Nomo’s games could be enjoyed. Dodger fans flocked to see him pitch and fans in all National League cities snapped up tickets in anticipation of his next starting assignment. His season kept building with excitement and Nomo’s very humble demeanor endeared him to baseball fans everywhere. The large Japanese American community in Southern California, particularly the Little Tokyo historic district in downtown Los Angeles, was fully vested in his success. The Dodger Line Drives newsletter and pocket schedules were printed in Japanese.

Walter F. Mondale, 42nd Vice President of the United States, who was 24th U.S. Ambassador to Japan, wrote a July 21, 1995 letter to Dodger President Peter O’Malley, “I believe that Nomo has done more for the U.S./Japan relationship than all the rest of us together and we are cheering him on.” Walter F. Mondale letter to Peter O’Malley, July 21, 1995

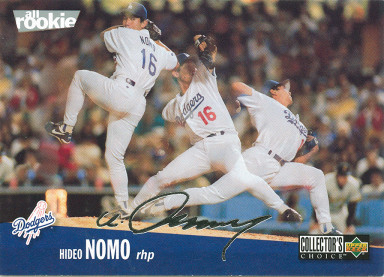

1996 All Rookie Dodgers baseball card featuring Hideo Nomo’s unique pitching delivery by Upper Deck Collector’s Choice.

The best major league hitters were baffled by his unorthodox “tornado” delivery, as he twisted and turned with his back to the batter in the wind-up before delivering the ball to home plate. By season’s end, Nomo was a hero on two continents, had won 13 games, led the National League in strikeouts (236) and was named N.L. Rookie of the Year, becoming the fourth consecutive Dodger to win that award.

O’Malley said, “This guy (Nomo) had the heart of a lion. There is no pressure that ever got in the way of Hideo Nomo. He handled pressure better than any professional athlete I’ve ever seen. The word ‘warrior’ came up, both here and in Japan.” He truly was a warrior.” Gordon Edes, Boston Globe, April 5, 2007

Nomo said, “It started with Peter O’Malley, Tom Lasorda and the staff that supported me and made it easy for me to concentrate on baseball.” Ken Gurnick and Austin Laymance, mlb.com, August 10, 2013

“The fans have fallen in love with him (Nomo),” said O’Malley. “They wanted to see someone new, someone fresh. They have savored every moment.” Bob Nightengale, Los Angeles Times, September 17, 1995

Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig who had seen the worst of times just a year before said, “Baseball needs good human-interest stories and the No. 1 story in baseball has been Nomo. Considering what baseball has gone through, with the strike and all our labor problems, the timing couldn’t have been better.” Ibid.

1996 Hideo Nomo baseball card by Score celebrating his 1995 National League Rookie of the Year award.

Others, including Nomo’s Dodger Manager Lasorda took it a step further stating, “It’s not too much to say that he saved Major League Baseball.” Robert Whiting, Japan Times, First of a four-part series, October 3, 2010 Columnist Nightengale wrote in The Sporting News, “Hideo Nomo not only saved the Dodgers, but perhaps all of baseball.” Bob Nightengale, The Sporting News, October 9, 1995 Mike Downey, Los Angeles Times columnist, wrote: “Hideo Nomo saved baseball…he was the best thing that could have happened to the game, at a time when baseball had nearly squandered its fandom forever. Nomo was something successful, something inspirational…Hideo Nomo was precisely the right man at precisely the right time.” Mike Downey, Los Angeles Times, September 7, 1995 One Japanese scholar said in 1995, “Nomo is better than 100 Japanese ambassadors to Washington.” Cameron W. Barr, Christian Science Monitor, “A Welcome Ray of Sunlight for Gloomy Japan,” July 5, 1995

The media frenzy continued with Nomo gracing the cover story of major publications like Sports Illustrated and both national and international editions of Time magazine and Newsweek. Sports Illustrated’s headline, “What’s Right About Baseball”: Rookie ace Hideo Nomo is just one reason the game is better than you think”. Countless Japan publications displayed him on covers, as well.

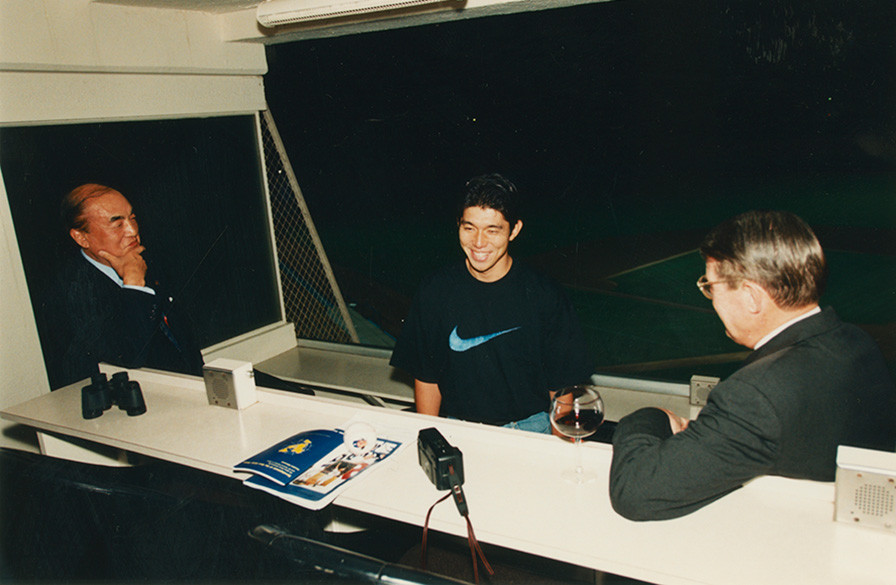

As “Nomomania” continued in 1996, he pitched one of the iconic games in Dodger history. Former Prime Minister of Japan Yasuhiro Nakasone visited Dodger Stadium on September 12 to watch Nomo pitch. Nakasone enjoyed the game with Peter O’Malley and met Nomo after his 4-1 win.

Former Japan Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone (left) meets Hideo Nomo (center) on September 12, 1996. After pitching a 4-1 victory over the St. Louis Cardinals, Nomo went upstairs to the President’s Box at Dodger Stadium to meet Mr. Nakasone. Dodger President Peter O’Malley (right) hosted Prime Minister Nakasone for the game.

On September 17, Nomo and the Dodgers were at Coors Field, Denver, Colorado to play the Rockies. Rain delayed the start of the game for two hours. When he finally took the mound, it was sloppy as it continued to drizzle but the game started anyway. Nomo would go on to pitch a no-hitter, a 9-0 blanking of the Rockies in the most hitter-friendly park in baseball. It’s a feat that has never been duplicated in the years since at Coors Field. Of course, the game was televised live to Japan. Vin Scully, the greatest baseball broadcaster, said in the moment on the Dodger telecast, “Hideo Nomo has done what they said could not be done. Not in the Mile High City. Not at Coors Field in Denver. He has not only shut out the Rockies, he has pitched a no-hitter. And thank goodness they saw it in Japan!”

A special pin honors Hideo Nomo (No. 16) of the Dodgers. In 1995, Nomo was signed by Dodger President Peter O’Malley and became a sensation touching off the phenomenon known as Nomomania. He pitched 12 seasons in MLB, including 7 with the Dodgers.

Nomo continued pitching with the Dodgers, winning 16 games in 1996 and 14 in 1997. He was with the Dodgers in 1998 when the new Fox ownership traded him to the New York Mets. He returned to the Dodgers as a free agent in 2002, winning 16 games that season and again in 2003. His major league career consisted of 12 seasons (1995-2005, 2008) pitching for seven teams and 123 victories. Nomo added a second no-hitter while pitching for the Boston Red Sox in Baltimore on April 4, 2001, becoming one of only five pitchers to have one in both the National and American Leagues. He led the American League in strikeouts with 220 in 2001.

Japan Baseball Hall of Fame slugger Sadaharu Oh and Peter O’Malley meet on December 12, 2002 at O’Malley’s office. Oh and O’Malley admire the artwork of Japan-born pioneer pitcher Hideo Nomo painted by Hira Yamagata, a Los Angeles-based artist who specializes in silkscreen and vivid colors. Nomo personally presented this artist’s proof to O’Malley at Ginza Sushi-Ko restaurant in Beverly Hills.

After the Dodgers were sold by the O’Malley family in 1998, the Dodgers kept Dodgertown but eventually sold the land to Indian River County in 2001. The Dodgers decided to relocate their spring training home to Glendale, Arizona starting in 2009. That meant that Dodgertown sat idle for nine months in 2008-2009, until Minor League Baseball leased the land and created a year-round training site for multiple sports called “Vero Beach Sports Village”.

Two years later after sustaining heavy losses, Minor League Baseball was on the verge of permanently closing the site in 2011. But that is when O’Malley stepped up to prevent it. He, his sister Terry O’Malley Seidler, former Dodger pioneer pitchers and friends Nomo and South Korea’s Chan Ho Park were the founding partners to save Dodgertown. “I asked Chan Ho and Nomo to help me continue bringing amateur and professional teams from Korea and Japan, and they did,” said O’Malley. In 2012, O’Malley became responsible for its operation and, in 2013, renamed it “Historic Dodgertown – Vero Beach, Florida”. The baseball team from Meiji University of Tokyo, one of Big 6 Tokyo League teams, twice visited the complex to train (2013 and 2016).

Nomo was elected to the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame January 17, 2014, becoming the youngest player ever to be honored at age 45 and 4 months. He was just the third player elected in his first year of eligibility, following Victor Starffin, a Russian who pitched and won 303 games in Japan, and Tokyo Yomiuri Giants’ superstar Oh. Nomo was inducted into the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame on July 18, 2014 and O’Malley was on the field during the ceremonies prior to Nippon Professional Baseball All-Star Game at Seibu Dome, presenting a large bouquet of flowers to his friend.

A special 2014 display at the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame in Tokyo honors Dodger pioneer pitcher Hideo Nomo. That summer he was inducted into the Hall of Fame as the youngest player elected (45 and 4 months old).

July 18, 2014, Japan Baseball Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, Seibu Dome, Tokorozawa, Japan, (L-R): inductee Hideo Nomo; Peter O’Malley; Japan Baseball Commissioner Katsuhiko Kumazaki; inductee Koji Akiyama; Tsutomu Itoh; inductee Kazuhiro Sasaki; and Motonobu Tanishige.

On July 8, 2015, Nomo was at Dodger Stadium to celebrate the conferment ceremonies for O’Malley who received “The Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon,” the highest order for a citizen not from Japan, from the government of Japan. The pregame ceremonies were held on the field at Dodger Stadium and included video remarks by Oh and Nagashima. Nomo brought a bouquet of flowers to O’Malley and bowed in respect. Nomo said at a press conference, “I was very pleased to learn that Mr. O’Malley received this great honor by the Japanese government (conferred by Emperor Akihito). I understand his great contribution to Japanese baseball over many decades. Without his support and hard work to Japanese baseball, I wouldn’t be here.”

July 8, 2015, (L-R): Former Dodger pitcher Hideo Nomo; Peter O’Malley; and Hidehisa Horinouchi, Japan Consul General in Los Angeles. O’Malley receives the “Third Class, Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon” at Dodger Stadium during Dodger pregame ceremonies. It is the highest honor for a non-Japanese citizen.

Then Consul General of Japan in Los Angeles Hidehisa H. Horinouchi presented the decoration to O’Malley. Horinouchi was later appointed Ambassador of Japan to the Netherlands.

On January 17, 2015, former Dodger pitchers Nomo and Chan Ho Park were honored by Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig at the Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation dinner in Los Angeles as the first-ever recipients of the “Baseball Pioneer” award for their contributions to the game and unifying of countries.

March 21, 2017, World Baseball Classic, Dodger Stadium, (L-R): Hideo Nomo, Peter O’Malley, and Chan Ho Park. Two of the greatest pitchers from Asia are back at Dodger Stadium to watch the World Baseball Classic.

Nomo’s legacy continues as he opened the door for more than 65 more Japan-born players to play in Major League Baseball (to begin the 2025 season). A posting system by Nippon Professional Baseball is now in effect for MLB clubs to sign talent from Japan. If it weren’t for Nomo’s desire to face the best hitters in America, other Japan-born superstars might never have made the move to the major leagues, thus a direct line can be drawn from him to Hall of Famer Ichiro Suzuki and the Dodgers’ Shohei Ohtani, with many star players in between and more on the way.

“A really big influence was when (Hideo) Nomo signed a contract to play in the major leagues with the Dodgers,” said Ichiro. “Up until then, it was merely an image in my mind, but when I saw Nomo play on television, the thought of playing in America became much clearer.” Jeff Idelson, Memories and Dreams, National Baseball Hall of Fame magazine, July/August 2006

Ichiro visited Peter O’Malley at Dodger Stadium on December 18, 1995 during a personal trip to the U.S. Two people he really wanted to meet during his stay were O’Malley and NBA superstar Michael Jordan. Ichiro had just helped the Orix Blue Wave to the 1995 Pacific League title in Japan and won his second batting title. Upon meeting the Dodger President, Ichiro told him through Acey Kohrogi, Dodger Assistant to O’Malley and interpreter, “Mr. O’Malley, I have your picture on my desk.” O’Malley told the Japanese newspapers, “He’s an outstanding young man, and I am proud and happy to have met him.” Three days later, Ichiro met Jordan in Chicago.

Nomo works for the San Diego Padres as an advisor in baseball operations, helping to support and instruct pitchers. He also established an industrial league team in the Osaka region of Japan in 2003, called “Nomo Baseball Club,” which gives non-drafted players (semi-professional) an opportunity to compete. He and his youth teams have made regular summer visits to Los Angeles and O’Malley always hosted a welcome dinner at Lawry’s for them.

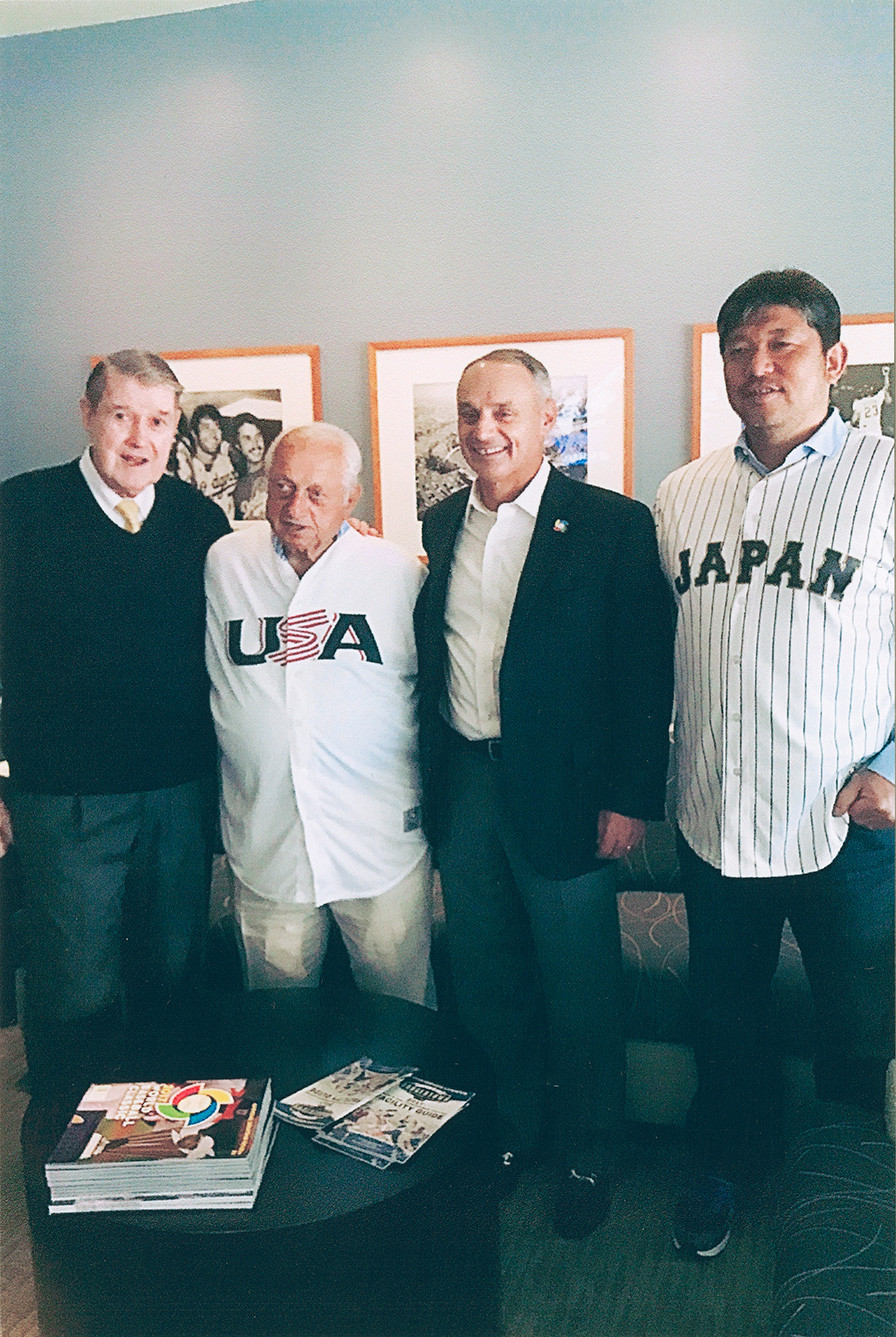

March 21, 2017, (L-R): Peter O’Malley, President, Los Angeles Dodgers (1970-1998); Hall of Fame Dodger Manager Tommy Lasorda; Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred; and Hideo Nomo are enjoying the 2017 World Baseball Classic at Dodger Stadium.

On May 9, 2016, an article about the Dodgers’ 1956 Goodwill Tour to Japan ran in The Wall Street Journal with the headline: “Sixty Years Ago, the Dodgers Toured Japan and Changed Baseball Forever”. Brad Lefton, The Wall Street Journal, “Sixty Years Ago, the Dodgers Toured Japan and Changed Baseball Forever” The article by Brad Lefton focuses on the friendship that started between the O’Malley family and Tokyo Yomiuri Giants, as the National League Champion Dodgers made the 19-game tour in the fall of 1956 throughout Japan. Since that trip, the friendships continued to grow as the numerous cultural exchanges advanced, including five team trips by Yomiuri to Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida for training. When Dodger President Peter O’Malley made the free agent signing of pitcher Hideo Nomo in 1995, baseball would never be the same in America and Japan.