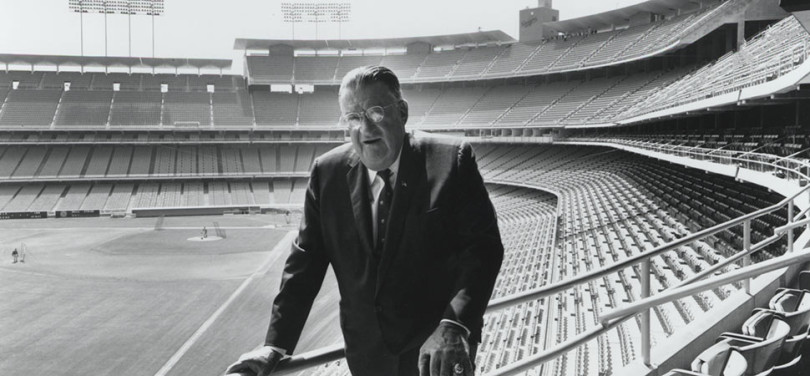

Walter O’Malley outside of his office on the Club Level at Dodger Stadium. O’Malley designed, privately-financed and built Dodger Stadium and is also credited with the westward expansion of Major League Baseball prior to the 1958 season.

Biography

Walter O’Malley

By Brent Shyer

Walter O’Malley’s Legacy

Walter O’Malley established a legacy as one of sport’s top visionaries and businessmen, building a first-class organization based on long-term stability and success. As President of the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers, one of baseball’s most enduring and beloved teams, he inscribed his reputation as an astute owner.

In his pioneering move of the Brooklyn Dodgers to the West Coast, he advanced the nationwide growth and success of the sport. O’Malley’s crowning achievement was designing, privately financing and building Dodger Stadium, the finest baseball ballpark of its time and, more than 60 years after it opened, remains as one of Los Angeles’ most recognizable and popular landmarks.

On December 3, 2007, O’Malley was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in its ballot of executives/pioneers. Induction ceremonies were held on July 27, 2008 in Cooperstown, New York. In December 1999, The Sporting News named O’Malley the 11th Most Powerful Person in Sports over the last century, while ABC Sports ranked O’Malley in its Top 10 Most Influential People “off the field” in sports history as voted by the Sports Century panel.

Walter O’Malley (circa 1907) with his parents, Edwin J. and Alma O’Malley.

Walter O’Malley proudly wears his Boy Scouts of America uniform (circa 1916).

The Early Years

Walter Francis O’Malley, son of Edwin Joseph and Alma Feltner O’Malley, was born in the Bronx, New York on October 9, 1903. Although he was an only child, he had many cousins nearby because his mother was one of eight sisters and brothers and the O’Malley family, originally from County Mayo, Ireland, numbered 14. Edwin O’Malley was the third oldest, became a dry goods merchant and later was appointed the New York City Commissioner of Public Markets (1919-1926) by Mayor John F. Hylan. Walter was a baseball fan of the New York Giants as a youngster, frequenting the old Polo Grounds with his uncle Clarence Feltner. When his parents moved from the Bronx when he was seven, O’Malley attended Public School No. 35 in Hollis, Long Island. O’Malley enjoyed the freedom of the outdoors, including hunting, swimming, fishing and boating. He was also active in Boy Scouts, an organization which had a profound influence on him.

Walter O’Malley on his Childhood

After attending New York’s Jamaica High School for two years (1918-20), O’Malley’s parents enrolled him at Culver Military Academy in Culver, IN. It was as a cadet at Culver that he wrote about sports and became associate editor for the student newspaper. He tried to play baseball at Culver, but the bespectacled first baseman’s career was cut short, however, as he was hit on the nose by a ball.

Walter O’Malley on his School Days

O’Malley next attended the University of Pennsylvania, where his leadership abilities, outgoing personality and understanding of politics guided him to become elected twice as class president, his junior and senior years, and the school’s first back-to-back winner in 25 years. At Penn, he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree while focusing his studies on elective subjects that would lay the groundwork for a possible career in engineering. O’Malley served on the council on athletics, choosing to oversee baseball rather than the more prominent football program. He chaired the Penniman Bowl contest for two years, was President of the Theta Delta Chi Fraternity and a member of the Scabbard and Blade Honorary Military Fraternity. He graduated as the outstanding overall student at Penn in 1926, receiving the prestigious “Spoon Man” award and was the senior class Salutatorian. In 1926, O’Malley attended Columbia Law School in New York, where he enrolled prior to his father, Edwin, losing the family’s savings in the stock market crash and Depression.

As the winner of the prestigious “Spoon Man” award at the University of Pennsylvania in 1926, Walter O’Malley graduates as the outstanding overall student in his senior class.

He worked three day-jobs as a junior engineer for the city of New York Board of Transportation, and also as a surveyor (for the city and he started his own company), while resuming his law studies at night at Fordham University. After earning his law degree on October 15, 1930, O’Malley founded and edited the “Sub-Contractors Register,” a directory useful to builders in 1931, and he wrote a law guide explaining the New York City Building Code.

On September 5, 1931, O’Malley married his childhood sweetheart Kay Hanson, in St. Malachy’s Church in New York. The Hanson family and the O’Malleys were neighbors on Ocean Avenue in Amityville, Long Island and a romance developed between the “girl next door” and her Prince Charming. In 1927, Kay was diagnosed with cancer of the larynx and underwent experimental surgery and as a result, she was unable to speak above a whisper. However, O’Malley knew that she was the “same girl I fell in love with” Jim Murray, Los Angeles Times, August 10, 1979 and they were united.

O’Malley shifted his focus from engineering to begin his law practice in New York’s Lincoln Building, specializing in corporate reorganization. He was sworn in on April 10, 1933 in Manhattan’s 1st Judicial Department. That same year, the first of the O’Malley’s two children, daughter Terry, was born. Their son Peter was born in 1937. The family lived in an apartment on St. Marks Avenue in Brooklyn, and O’Malley purchased Dodger season tickets at Ebbets Field for family enjoyment and the entertainment of clients.

September 30, 1931, Walter and Kay O’Malley on their honeymoon in Bermuda. Kay and Walter were married in St. Malachy’s Church, 239 West 49th Street, New York City, September 5, 1931. Newly-ordained Father Patrick Gallagher was the Celebrant of the Mass and was always a close family friend. Kay’s sister Helen Hanson (Walsh) was the Maid-of-Honor and Al Alvino was the Best Man. The meal at Lindy’s after the wedding included lamb chops and Chauvenet Red Cap which became an Anniversary tradition. They sailed to Bermuda on the Franconia from the 80th Street Pier for their honeymoon. This photo was taken as they left the Belmont Manor September 30 on a horse-drawn carriage to board their ship to sail back to NYC and their apartment at 2 Beekman Place. They certainly lived happily ever after — for 47 Anniversaries on the East Coast and West Coast — and now in Heaven!

Walter and Kay O’Malley with their children, Peter and Terry, circa 1939.

O’Malley Dodger Connection

It was while practicing law that O’Malley connected with George V. McLaughlin, the powerful civic leader and Brooklyn Trust Company president. McLaughlin, known as George the Fifth, was as close as anyone who could be called a mentor to O’Malley. While still at Penn, O’Malley’s father, Edwin, had introduced him to McLaughlin, the former New York City Police Commissioner. The nearly bankrupt Dodger organization was in arrears in paying its mortgage loans to the Trust Company and O’Malley was assigned by McLaughlin to keep an eye on the ballclub’s legal and business affairs, whose financial condition was in question.

Eventually, O’Malley made another bold career move, permanently leaving his successful New York law practice in 1943 to join the Dodgers as their full-time Vice President and General Counsel, replacing former U.S. presidential candidate Wendell L. Willkie, who was in ill health and had left to publish his book, “One World.” O’Malley was presented opportunities to purchase stock in the ballclub in two separate transactions in 1944 and 1945. On November 1, 1944, he joined with Dodger President Branch Rickey and Andrew Schmitz, a prominent Brooklyn insurance executive to purchase 25 percent of the stock from the estate of former part-owner Ed McKeever. In the second transaction on August 13, 1945, O’Malley, Rickey and John L. Smith, who was then Vice President and later President of Pfizer Chemical, purchased 50 percent of the stock from the estate of Charles Ebbets. Schmitz sold his shares to the triumvirate, raising their total stock held to 75 percent, with the balance owned by Dearie McKeever Mulvey, daughter of the late Brooklyn team President Steve McKeever.

An original Brooklyn Dodger stock certificate issued to Walter O’Malley and signed by Dodger President Branch Rickey on Sept. 25, 1945.

Stationery from Walter O’Malley’s law offices, with partner Ray Wilson, at 60 E. 42nd Street in New York City.

In 1946, O’Malley wrote Capt. Emil Praeger for his architectural ideas to either renovate or design a new ballpark in Brooklyn. The former Naval Captain was an engineer for the renovation of the White House in 1949 and several United Nations buildings in New York in 1953. Praeger would later play a major role in the design of Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, teaming with O’Malley on the 11th stadium site for which they prepared plans and blueprints. Also in 1946, Rickey signed four-sport star Jackie Robinson to a Montreal Royals minor league contract, which led to the historic 1947 breaking of the color line in Major League Baseball. At the time, O’Malley was part-owner, Vice President and General Counsel of the Dodgers.

A shift of Dodger Presidents on Oct. 26, 1950, as 47-year-old Walter O’Malley purchases controlling interest in the Brooklyn ballclub and takes the reins from the departing Branch Rickey.

Aging Ebbets Field

Always one to be involved with extracurricular activities, O’Malley took time for recreation, organizing and serving as chairman of the popular U.S. Atlantic Tuna Tournament in Belmar, NJ in 1938 and in the 1940s, with the exception of the war years.

O’Malley purchased J.P. Duffy, a building supply company and, in 1950, the New York Subways Advertising Company.

In October 1950, O’Malley purchased additional stock from Rickey. The partners had agreed to offer their shares of stock first to each other with a right to match the terms, rather than to an outside buyer if they were ever to sell. O’Malley and Smith’s widow, May, were offered Rickey’s stock at $1,050,000.

With his 50 percent ownership, 47-year-old O’Malley became President and majority owner of the Dodgers on October 26, 1950. His top priorities were to make the needed improvements on aging Ebbets Field and to continue Branch Rickey’s theory that a strong minor league system results in a competitive major league team.

As a youngster, Walter O’Malley always had an interest in fishing which continued through his adult years. He was the organizer of the U.S. Atlantic Tuna Tournament in 1938 and chairman of the popular event, which began in Belmar, NJ. The tournament was also held in the 1940s, with the exception of the war years.

Utilizing his diverse educational background, O’Malley concentrated his efforts on identifying a site to privately build a new stadium in Brooklyn to replace an aging Ebbets Field, built in 1913, with its limited parking for 700 cars. He focused his energy on a location at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues in Brooklyn, which included the Long Island Rail Road terminal, access to every subway line in New York and the Ft. Greene Meat Market. O’Malley’s plan was to improve and redevelop the congested area, if he could get assistance in assembling the land, which he was going to purchase and build his stadium with ample parking. On June 25, 1953, in a letter he wrote, “It is my belief that a new ball park should be built, financed and owned by the ball club. It should occupy land on the tax roll. The only assistance I am looking for is in the assembling of a suitable plot and I hope that the mechanics of Title I (of the Housing Act of 1949) could be used if the ball park were also to be used as a parking garage.” Walter O’Malley letter to William Tracy, Vice Chairman, Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, June 25, 1953

Powerful Robert Moses, the New York parks commissioner and master planner for bridges, highways, housing and construction in the entire area, had other plans. While he seemed to be more than a little interested in O’Malley’s ideas and plans through their numerous exchanges of correspondence over several years, Moses in reality was not willing to improve the Long Island Rail Road site in Brooklyn, since the very thought of massive public transportation would have cost jobs and cut the very heart out of the highways and bridges system used by automobile transportation to the suburbs which he was trying to promote. George DeWan, The Master Builder, www.lihistory.com and Neil Sullivan, The Dodgers Move West, Oxford University Press, 1987, pp. 50-51

Dome Stadium Vision

O’Malley wanted to build the first domed stadium for baseball (as well as other sports). The idea was at least 10 years ahead of its time, as the Astrodome in Houston, Texas was not opened until 1965. In the early 1950s, O’Malley talked to Norman Bel Geddes about renovating Ebbets Field or a dome stadium design. Later, O’Malley worked with famed innovator-architect R. Buckminster Fuller to design a 50,000-seat geodesic clear span dome with a retractable roof for Brooklyn. He wrote a letter to Fuller on May 26, 1955, “I am not interested in just building another baseball park.” This was followed by Fuller’s students in a graduate class at Princeton University architecturally designing a domed stadium. Graduate student T. William Kleinsasser, Jr. heard the tail end of one of Fuller’s lengthy “guest” lectures. Later, he was prodded by his French class professor to incorporate Fuller’s ideas to help the situation involving the Dodgers and their search for a new stadium by designing a domed model in November 1955. The Dodger domed stadium would have been a showcase for all of baseball and, practically speaking, avoided costly rainouts and provided year-round entertainment for the citizens of Brooklyn and beyond.

The net effect on Brooklyn would have meant the Dodgers stayed put, playing in a privately-financed state-of-the-art stadium; a new meat market; improved and modern rail service; and less traffic congestion in the redeveloped area.

Ebbets Field provided a cozy atmosphere for Dodger fans in Brooklyn, but the stadium’s age plus limited seating and parking capacities prompted Walter O’Malley’s quest for a new ballpark.

Walter O’Malley inspects a geodesic domed stadium model with architect R. Buckminster Fuller at Princeton University in November 1955.

Photo by Wil Blanche. Copyright © 1955. All Rights Reserved.

Buckminster Fuller (left) confers with Dodger President Walter O’Malley in 1956 regarding the use of a geodesic dome to contain a new baseball stadium in Brooklyn. Fuller, an internationally known inventor, designer, and professor, was a judge at a competition for architectural students at Princeton University and O’Malley was present to review student designs for a baseball stadium.

Courtesy of Department Special Collections Stanford University Library

While he explored all options off the field, O’Malley’s Dodgers enjoyed success on the field. In 1951, the Dodgers had lost the National League Pennant in devastating fashion to the New York Giants and Bobby Thomson’s legendary “Shot Heard ‘Round The World.” In 1952 and 1953, the Dodgers won the N.L. Pennants but lost to the Yankees twice more in the World Series. Following the 1953 season, O’Malley rejected Manager Charlie Dressen’s request for a multi-year contract and turned to a relatively unknown baseball man, Walter Alston. The “Quiet Man” from Darrtown, OH, who played in one major league game, became Dodger Manager amongst blaring headlines “Walter Who?” However, Alston had been a successful organizational manager, piloting St. Paul (MN) to the American Association Pennant in 1948 and the Montreal Royals to the “Little World Series” title against the New York Yankees’ Kansas City club in 1953. He signed the first of 23 consecutive one-year contracts in a gentleman’s agreement with O’Malley. Alston went from relative obscurity to immortality as he was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983.

On September 23, 1954, Walter C. Peterson, City Clerk for the City of Los Angeles, sent a letter to O’Malley and all team owners expressing the City Council’s desire to “start action in an effort to bring Major League Baseball status to the City of Los Angeles.” O’Malley received a letter in September 1955 from L.A. City Councilwoman Rosalind Wyman who reiterated the interest of the city and tried to persuade him to meet with her and others about relocating the Brooklyn Dodgers there. Rosalind Wiener Wyman, Councilwoman 5th District, L.A., letter to Walter O’Malley, Sept. 1, 1955 Since he was focused on a solution in Brooklyn, O’Malley responded to her that he was not interested in meeting. O’Malley letter to Rosalind Wiener Wyman, September 7, 1955

Walter Alston and Walter O’Malley appear at the manager’s introductory news conference on Nov. 24, 1953.

1955 World Champions

Meanwhile, in 1955, the Dodgers jumped out of the starting gate with 10 straight victories, went 22-2 and never looked back. Second-year Manager Alston led the Dodgers to their first and only World Championship in Brooklyn, as they defeated their old nemesis, the Yankees in seven games. On October 4, 1955, as the Dodgers and Johnny Podres won 2-0, finally the old adage of “Wait ‘Til Next Year” could be retired once and for all, as the Borough of Brooklyn overcame its second-class citizen complex and glowed in the spotlight.

Attendance chart shows the Milwaukee Braves at Milwaukee County Stadium, opened in 1953, outpacing the Dodgers who were playing at aging Ebbets Field in Brooklyn.

But attendance, though good, was not keeping up with other clubs like the Milwaukee Braves, who had relocated from Boston in 1953 into a new municipal ballpark and were drawing in excess of two million fans at home compared to Brooklyn’s one million. This was of major concern to O’Malley who wanted his Dodgers to remain competitive in all areas on and off the field. In the long term, he believed, the Dodgers would have to build a new family-friendly stadium with improved sightlines and increased parking facilities since a large number of fans were moving from Brooklyn to the suburbs of New York. By expanded use of the automobile, it became feasible to live in the suburbs and commute. After a 50-year drought of shifting of teams, relocation became one possible solution to a number of franchises.

Jubilation in the Dodger clubhouse as Walter O’Malley and second-year Manager Walter Alston embrace as the Dodgers win their first World Championship on Oct. 4, 1955. The Dodgers defeated the New York Yankees, four games to three, with a 2-0 clincher in the seventh game at Yankee Stadium.

O’Malley built and maintained Dodgertown in Vero Beach, FL, the highly-regarded spring training site, which included 5,000-seat Holman Stadium, which was designed and engineered by Capt. Praeger. Dodgertown was once the site of a U.S. Naval Air Station in World War II, but the Dodgers leased the land and held spring training there beginning in 1948, using the old barracks to house the major and minor league players and coaching staffs.

As part of the player development system, it was Rickey’s vision to have a baseball factory where the players were the widgets and he could push the best ones up the ladder to the majors. The raw talent of more than 600 young ballplayers on 26 minor league teams was developed through instruction and practice at Dodgertown. The players would eat in the mess hall, sleep in the temporary Naval barracks with no heating or air conditioning and train on the numerous fields, in the batting cages and pitchers’ strings area. Nearly every Dodger great trained at Vero Beach. With his vision of how to develop the complex, O’Malley took the bare bones training camp and elevated it to a new level, first signing a 21-year extension on a lease with the city on January 30, 1952 and later purchasing the land in the early 1960s. On March 11, 1953, O’Malley dedicated the intimate new ballpark to Bud Holman, the influential General Motors automobile dealer in Vero Beach and Eastern Air Lines director, who had originally encouraged the Dodgers to train in Vero Beach.

Dodgertown aerial view showing the old two-story barracks at the former U.S. Naval Air Station. Walter O’Malley worked on a series of improvements to develop the spring training site in Vero Beach, FL beginning in the spring of 1951, his first year as Dodger President.

Photo courtesy of Indian River County Historical Society, Inc.

Walter O’Malley is presented the key to Vero Beach, FL as Dodgertown becomes the long term home for spring training activities.

International Baseball Outreach

Devoted full-time to baseball, O’Malley was named to the important leadership committee, the Major League Executive Council in 1951 and served until 1978, the longest tenure ever. He resolved challenges and helped shape the course of Major League Baseball, as one of its most influential and forward-thinking owners. O’Malley dealt with issues ranging from television, antitrust exemptions, selection of three Commissioners of Baseball and player pension plans, to the global expansion of the game.

While helping to direct baseball’s complicated business matters and solve issues of that era, O’Malley passionately guided his own organization to prominence on and off the field. In fact, the Dodgers, encouraged by the State Department, made an important goodwill tour to Japan following the 1956 season, even visiting Hiroshima, which had been the recipient of the U.S. atomic bomb just 11 years earlier. But, O’Malley believed in the unity of nations in a sports setting, forging partnerships that were built for the common good of the game and each country. The Dodgers made another successful trip to Japan in the fall of 1966. Invited by O’Malley, the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants made reciprocal visits to use the training facilities at Dodgertown in 1957 (2 players and the manager) and team trips in 1961, 1967, 1971 and 1975.

During their 1956 Goodwill Tour to Japan, the Dodgers visit Hiroshima and its memorial. Later that day, the Dodgers dedicate a bronze plaque at the entrance to the new ballpark.

A luggage tag from the 1966 Dodgers Goodwill Tour to Japan.

O’Malley’s international outreach was widespread, as the Dodgers staffed nearly entire teams in Winter Leagues in the Dominican Republic, Cuba and Puerto Rico, sent scouts to search for talent around the globe and conducted educational exchanges. They invited representatives from many countries to study and learn about coaching and training techniques at Dodgertown. As early as 1964, the Dodgers made a trip to Mexico City to play exhibition games against the Red Devils. Mexico’s President Adolfo Lopez Mateos was in attendance and tossed the ceremonial first pitch.

When the Dodgers made the transition to Los Angeles following the 1957 season, O’Malley had exhausted all political possibilities in his desire to remain in Brooklyn and to privately finance the stadium. The Dodgers played seven “home” games at Jersey City, New Jersey’s Roosevelt Stadium in 1956 and eight in 1957, as O’Malley made it known to officials that there was an urgency in getting a response to his quest for land and a final solution to the aging Ebbets Field problem. He had sold 43-year-old Ebbets Field in October, 1956 and leased it back for three years to give him time to build a new stadium. O’Malley had identified land and tried to work with the frustrated New York Governor-approved Brooklyn Sports Center Authority, which was under funded and stalled in getting its business off the ground. Additionally, he had heard varied suggestions about where to relocate the Dodgers, including one idea between a cemetery and a body of water, to which O’Malley responded, “I don’t think we’ll get many customers from either place!” Time Magazine, “Walter In Wonderland,” April 28, 1958 He also paid a hefty five percent New York City admissions tax, resulting in a payment of $165,000 per year. The jovial Irishman seemed to take most of the rejection in stride, as he did not want to leave his own New York roots, but he had simply run out of feasible options.

Walter O’Malley confers with Jersey City, NJ officials to use Roosevelt Stadium for selected Dodger home games in 1956 and 1957 on Aug. 22, 1955, while he tries to find a permanent solution to the aging Ebbets Field problem. Seated next to O’Malley is Mayor Bernard Berry of Jersey City, while standing from left are Jersey City Comissioners Lawrence Whipple and Joshua Ringle, along with Dodger Vice President Fresco Thompson.

AP Photo

On May 2, 1957, Walter O’Malley takes a 50-minute helicopter ride to view prospective sites for Dodger Stadium. From left is Los Angeles County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn, Undersheriff Peter Pitchess, Del Webb, co-owner of the New York Yankees, O’Malley and pilot Capt. Sewell Griggers at Biscailuz Center.

An airborne Walter O’Malley described the helicopter ride to view Los Angeles area land on May 2, 1957 by stating, “I was never so scared in my life.” The door on the side of the helicopter had been removed so that O’Malley would have an unobstructed view of the ground and possible sites for Dodger Stadium.

© Getty Images

Elected Officials Disagree

O’Malley was rebuffed by politicians in his attempt to assemble the land, pay for it and then privately build a domed stadium for the Dodgers in Brooklyn. Without the backing of Moses, who was pushing towards Flushing Meadows in Queens, O’Malley eventually chose the course of relocating the Dodgers to Los Angeles. It would change baseball forever, expanding its borders nearly 1,500 miles beyond the previous boundary of Kansas City in the American League to the burgeoning West Coast. While at the same time, O’Malley knew the longtime rivalry with the New York Giants should continue, even if one of them were to move. Giants’ owner Horace Stoneham had privately made it known to O’Malley that he was planning on moving his team to St. Paul, MN (the site of his Triple-A team), as the old Polo Grounds, built in 1911, like Ebbets Field, was also dilapidated and suffering from sagging attendance. O’Malley suggested to Stoneham to take a serious look at San Francisco because travel expenses for all National League teams could be reduced if two clubs moved to the West Coast.

Stoneham’s new suitor became San Francisco, which was approaching major league teams and, unlike Los Angeles, its voters had agreed to fund and build a municipal stadium through a $4.5 million bond issue. Through a meeting arranged by O’Malley in New York, Stoneham discussed this move with San Francisco Mayor George Christopher. The Giants were ready to relocate in 1957 and San Francisco officials were eager to bring them to the West Coast. O’Malley, though, had his own problems to resolve.

He had to clear hurdles at every turn both in New York and when he initially moved to Los Angeles, but he was determined to make the right decisions and effectively direct his winning organization.

Los Angeles was a city in transition with big league dreams. The highest level of baseball played was in the Class Triple-A Pacific Coast League. O’Malley made a February 21, 1957 trade with Philip K. Wrigley, giving the Chicago Cubs’ owner the Texas League Ft. Worth team in exchange for Wrigley Field in L.A. and the Los Angeles Angels in the PCL. This swap provided O’Malley with the ability to secure territorial rights to Los Angeles if he later decided to make the big move. It would come with a hefty price tag, however, as O’Malley and the Giants each had to pay $450,000 to the PCL for those territorial rights. Each remaining PCL team received a share of the fee.

Voters in L.A. had turned down a June 1, 1955 ballot measure to finance a baseball stadium through municipal bonds which then lessened the chances of attracting a major league team. The apathetic vote meant the proposition’s $4.5 million bond issue was sunk. Understanding the importance of this vote, O’Malley saved the newspaper clipping on this topic. Gladwin Hill, New York Times, June 2, 1955, “Los Angeles Vote Vetoes Ball Park” article He realized that any owner who was headed west would have to take the enormous burden of financing and building a baseball stadium himself. But, to O’Malley it was an ideal match, as he wanted to wrap all the best features he had observed into a ballpark of his building. With his engineering background, it was a perfect combination.

Los Angeles officials approached O’Malley about moving there and, no doubt, he was skeptical at first, because of surroundings which were both unfamiliar and sprawling. But, then he realized the potential of the market, including a fine location to build his dream stadium and the great weather (no domed stadium would be needed in sunny Southern California). It is said that when O’Malley saw rugged Chavez Ravine, also referred to as Goat Hill, on a May 2, 1957 sheriff’s helicopter ride, he correctly estimated the amount of dirt that would have to be moved at nearly eight million cubic yards. He was also duly impressed by the confluence of freeways that surrounded the rugged terrain.

As they arrive in Los Angeles on their own airplane on Oct. 23, 1957, Dodger President Walter O’Malley steps off the plane to a welcoming committee headed by key supporters County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn and L.A. City Councilwoman Fifth District Rosalind Wyman.

Big League Dreams

On May 28, 1957, the National League, meeting in Chicago, granted the Giants and the Dodgers the permission to move to San Francisco and Los Angeles if the two clubs sought to make that shift together by October 1 of the same year. In addition, a unanimous vote of all eight National League teams was required for approval of the West Coast move.

O’Malley also spent a great amount of time in August 1957 working on details of a possible agreement to bring the Dodgers to Los Angeles. The negotiator tabbed in early July 1957 by the city and the County Supervisors of Los Angeles was Harold “Chad” McClellan, the former Under-Secretary of Commerce for International Affairs in the Eisenhower Administration, who took over where earlier discussions in March in Vero Beach and May in Los Angeles had commenced. The first meeting between McClellan and O’Malley was in Brooklyn on August 21, 1957, just two days after the Giants announced they were moving to San Francisco.

Last-ditch efforts by New York officials to keep the Dodgers proved futile, including Mayor Wagner’s attempt to embrace Nelson Rockefeller’s plan to finance the land on which to build a new ballpark. Moses, who thwarted any thoughts of the Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues site in Brooklyn, had stonewalled the efforts of O’Malley. Like so many before and after him, O’Malley knew it was time to head west to new frontiers.

Chavez Ravine would provide a spacious, but challenging construction site for the new Dodger Stadium.

The July 24, 1950 letter from the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles to residents of Chavez Ravine regarding a public housing development to be built on the site for low-income families.

On October 7, 1957, the Los Angeles City Council voted 10-4 to pass a motion to officially ask the Dodgers to relocate to their city and entered into a contract with them to exchange land at Chavez Ravine for Wrigley Field in Los Angeles. The contract obligated O’Malley to privately fund and build a 50,000-seat stadium, in addition to putting the land back on the tax rolls. The next day, the Dodgers’ publicist Red Patterson issued the following announcement from New York: “In view of the action of the Los Angeles City Council yesterday and in accordance with the resolution of the National League made October first, the stockholders and directors of the Brooklyn Baseball Club have today met and unanimously agreed that the necessary steps be taken to draft the Los Angeles territory.”

However, problems arose from the start, and as O’Malley stepped off the Dodger airplane in Los Angeles on October 23, 1957, he was greeted not only by a welcoming committee and well-wishers, but with a summons served on behalf of a few residents living illegally in Chavez Ravine.

The area, named for former Los Angeles Councilman Julian Chavez, was the site of the federal government’s failed public housing project in the early 1950s and the land had reverted back to the City of Los Angeles with limited-use restrictions. No one was supposed to be living on the land, as the Housing Authority of Los Angeles had sent letters to the residents as early as July 24, 1950 informing them that “a public housing development will be built on this location for families of low income…It will be several months at least before your property is purchased. After the property is bought, the Housing Authority will give you all possible assistance in finding another home.” But, a handful of residents remained there illegally, despite being told repeatedly by city officials to relocate. As he did in New York, O’Malley took it in stride and stayed focused.

Where to Play?

Many ideas, from a zoo to a cemetery, had been discussed by city officials about how to use the Chavez Ravine land, but nothing materialized. Walt Disney also considered the land for his Disneyland project, but rejected it. Cary S. Henderson, Los Angeles and the Dodger War, 1957-62, Southern California Quarterly, Fall 1980, page 286 The city had purchased the land back from the federal government after the aborted public housing project of 24 13-story and 163 two-story buildings, which had been designed by famed architect Richard Neutra. Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson, youthful City Councilwoman Wyman and County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn were the influential leaders in bringing Major League Baseball to L.A., along with Los Angeles Examiner sports columnist Vincent X. Flaherty, who had been a longtime advocate of the idea. Flaherty had corresponded with O’Malley since 1953 suggesting that the Los Angeles market was ready for the majors and enthusiasm had never been higher. However, O’Malley would reply that he wanted to stay in Brooklyn and build a domed stadium there, leaving Flaherty the impression that he was chasing a real long shot.

Dissenters and owners of the San Diego minor league club, who didn’t want to lose a grip on the old Pacific Coast League, challenged the approved city contract with O’Malley. By late 1957, the naysayers amassed enough signatures on a petition to force a referendum to be voted on by the city’s populous in June of 1958.

In the meantime, O’Malley and club attorney Henry J. Walsh had to negotiate a place to play for the 1958 season on an interim basis while his dream stadium was to be built. After seriously considering the Rose Bowl in Pasadena and team-owned Wrigley Field in Los Angeles (capacity of 22,000), the Dodgers struck a lease deal with the Los Angeles Coliseum Commission to play games in the 100,000-seat Memorial Coliseum. O’Malley’s “Three a.m. Plan” as it was named, because it came to him in the middle of the night, allowed for minor modifications to be made to the shared facility (Los Angeles Rams, UCLA, USC, among others) and shoehorn the baseball field into the existing area. O’Malley’s idea was to lay out the field from the closed end with left field only 251 feet from home plate, but with a bizarre 42-foot high screen. That unusual dimension brought criticism from the press, but O’Malley knew it was a temporary solution until Dodger Stadium could be built. O’Malley’s new plan also mitigated the concerns of other Coliseum tenants who disagreed with the initial idea of changing the football playing surface or seating areas just to accommodate baseball. O’Malley paid $600,000 in rent for a two-year lease at the Coliseum, plus an initial $300,000 to convert the field for baseball use.

It would be in question whether the deal that the city had struck with O’Malley would be valid until a vote of the people on June 3, 1958. A yes vote on “Proposition B,” as the referendum was titled, meant that the contract with and approved by City Council should be allowed, while a no vote meant the agreement would be rejected by the voters. The major provision was that O’Malley was bound to build a 50,000-seat stadium on the property. The city would receive, in exchange, Wrigley Field at 42nd and Avalon from the Dodgers, plus putting the Dodger Stadium property on the tax rolls at some $345,000 per annum. In addition, the Dodgers would pay up to $500,000 for a recreational area for public use on 40 acres of the land located in the hills above the stadium. The Dodgers would also pay a maintenance cost for the recreation area at an additional $60,000 a year for 20 years. The Dodger Stadium land would also be restricted by its conditional use permit.

O’Malley’s Challenges

On June 1, 1958, the Dodgers aired a live, five-hour Dodgerthon on KTTV, from the studios and then from the airport as the Dodger team plane arrived, explaining the advantages of supporting the contract and the Dodgers in Los Angeles. Numerous noted celebrities including Dean Martin, George Burns, Jerry Lewis, Ronald Reagan, Debbie Reynolds, Joe E. Brown and Jackie Robinson partook in the festivities favoring the Dodgers. Every major business leader and association supported Prop B.

Two days later, the Referendum received 351,683 yes votes and passed by 25,785 votes. It was the largest non-Presidential election turnout in Los Angeles history, with over 62 percent of the city’s 1,105,427 voters casting ballots. O’Malley was about to start the groundbreaking of new Dodger Stadium, when once again legal challenges arose. The opposition appealed to two different State Superior Courts on the grounds that the city’s granting of the land use did not follow a “public purpose” clause in the Federal government sale to the city. A favorable ruling was immediately appealed by the city to the California State Supreme Court, which overturned both lower courts’ decisions. The unanimous first decision (7-0 vote) was on January 13, 1959 and the refusal to reconsider followed on February 11. In the meantime, California Governor Edmund G. Brown pledged to sell 36 acres of state-owned land in Chavez Ravine to the city of Los Angeles to complete the agreement on the stadium site for $170,780. Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1959

After additional attempts to appeal to the California State Supreme Court in April, 1959 by attorney Phill Silver, who represented the opponents of the city’s contract with the Dodgers, the court upheld the constitutionality of the agreement. The complaint eventually went to the U.S. Supreme Court, where an appeal request was not heard and was finally dismissed on October 19, 1959. The long process and expensive legal wrangling was over. In the meantime, while O’Malley was preparing by contract to exchange Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, valued at $2.25 million for the rough, hilly terrain of Chavez Ravine, another battle began, as a few remaining residents illegally living on the hills refused to leave, even though they had been ordered to years before and asked to voluntarily leave on March 9, 1959 before the eviction. Los Angeles Examiner, May 12, 1959

Residents were paid for their houses, but many felt that they should not have to leave, despite the property belonging to the city. O’Malley had acquired the land by contract with the city and was obligated to privately build Dodger Stadium on a portion of the land. But, what was the city’s stance of looking the other way on the area which was nearly dormant for six years, turned into O’Malley’s latest headache, even after he spent $494,200 to purchase 12 properties at greatly inflated prices. Records show the appraised total was $85,750, when the owners refused the city’s best and last offers in 1960. O’Malley had all legal right and title to the land, but nevertheless the remaining residents held it against him and not the federal government, Housing Authority or city officials. The fact remains, however, that no property owners should have been there after 1951-52 and the City Housing Authority’s edict to vacate.

On September 17, 1959, thousands of onlookers watch bulldozers charging down the hills to begin the massive leveling and grading process for Dodger Stadium at the groundbreaking ceremony. In all, eight million yards of earth were moved to prepare the rugged land for the building of Dodger Stadium.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

On September 17, 1959, some 5,000 enthusiastic onlookers joined the media and invited guests for Dodger Stadium groundbreaking ceremonies. Dodger players took positions along white lines that were an approximation of the diamond, but they were swarmed by autograph seekers. It was a proud day for Walter O’Malley, despite more costly delays until his “dream stadium” would become a reality in 1962.

Delmar Watson

Dodger Stadium Groundbreaking

Finally, on September 17, 1959, groundbreaking ceremonies were held for Dodger Stadium and O’Malley knew that his longtime dream of building his own stadium would be fulfilled. He thought it would be achieved in 1960, but later had to push back completion until April 1962. Because of the extensive delays, the price tag had also increased by $2.5 million to a new total of $23 million (including construction, roads and land acquisition). The Dodgers were forced to remain in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for two more seasons, with less than favorable last-minute lease terms from the Coliseum Commission.

Construction of Dodger Stadium, delayed by additional legal challenges, finally begins in earnest following Labor Day, 1960. The 19-month timetable is short, but O’Malley and the Vinnell Construction team vow to meet the 1962 opening.

Dodger Stadium was as well-designed as any park before or since. Most of its success was in the detailed planning process by O’Malley, along with Vice President Stadium Operations Dick Walsh, architect Capt. Praeger and Jack Yount of Vinnell Constructors. Two of O’Malley’s closest financial advisors during this stage were Dodger Directors Sylvan Oestreicher and Jim Mulvey, husband of part-owner Dearie Mulvey and President of Samuel Goldwyn Pictures. Union Oil, the team’s first major sponsor, and Bank of America were key players in the financial aspects of Dodger Stadium construction.

During the complicated construction process, O’Malley was totally immersed in the project, as he resided in downtown Los Angeles at the Statler Hotel at 930 Wilshire Boulevard. He never wanted to be far away from the site. Almost every conceivable idea for the new ballpark was discussed and considered by O’Malley: ease of parking; transportation from the lots to the stadium; exclusive Club Level seating; lighting; colors; width of seats; concessions; landscaping; artwork; fountains; restroom availability; cleanliness; sightlines; escalators; fine dining; and a milk bar for kids, among others. When the Dodgers were in Japan in 1956, O’Malley noted the unique ground’s eye view provided from dugout box seats and he incorporated the concept into his new stadium. The influence of Disneyland for its layout, parking facilities and high level of customer service did not go unnoticed by O’Malley, who had his executives visit the Magic Kingdom and take notes.

On Opening Day of Dodger Stadium, April 10, 1962, Peter O’Malley looks on as his mother Kay gets ready to throw out the ceremonial first pitch using an autographed team baseball from behind the Dodger dugout in the Field Level seats.

The Dodgers and Cincinnati Reds played on Opening Day of Dodger Stadium, April 10, 1962. The Dodgers lost that day to the Reds, 6-3, but would win their first game at Dodger Stadium the next day, 6-2, behind pitcher Sandy Koufax. Dodger Stadium was the first stadium to be privately built since Yankee Stadium in 1923.

An aerial view of Opening Day 1962 with its record crowd of 52,564 as the Cincinnati Reds defeated the Dodgers, 6-3, on a three-run home run by veteran Wally Post.

AP Photo

O’Malley’s efforts resulted in rave reviews for Dodger Stadium which opened on April 10, 1962, becoming an instant hit and favorite from the casual fan to the season ticket holder. His wife, Kay, tossed the ceremonial first pitch from behind the Dodger dugout on the Field Level to catcher John Roseboro. Fan acceptance of Dodger Stadium, as evidenced by the Opening Day enthusiasm, was O’Malley’s proudest moment. With column-free construction, an unobstructed view of home plate made every seat in Dodger Stadium a good one. While some writers played up the fact that there were only two drinking fountains at Dodger Stadium when it opened, Dodger executive Red Patterson conveyed to O’Malley that only a handful of complaints had been received by fans on that topic. Immediately, the minor oversight was corrected to the satisfaction of all.

Fans were impressed by the beauty of the multi-colored levels and its symmetry, plus the stunning views of the San Gabriel Mountains and downtown Los Angeles. O’Malley was always interested in horticulture and spent an additional $1.5 million on colorful landscaping in 1963, including gardens and planting a variety of trees Trees include 1,000 Eucalyptus, 1,000 Acacia, 750 Fiscus-Nitida, 150 California Peppers, 95 Olive, 85 Canary Island Pine, 75 Washingtonia Palms, 75 Brazilian Peppers, 36 Evergreen Ash, 34 Chinese Elms, 20 Orchids, 20 Jacaranda, 20 Date Palm, 12 Mediterranean Palms, 12 Evergreen Pear and 10 California Rosewood, in addition to 300 Olympic Rose bushes according to 1990 “Dodger Stadium A to Z” brochure making Dodger Stadium more than just a baseball park, but an oasis and showplace in Los Angeles. Since the day it opened, nearly 150 million people have attended games at Dodger Stadium through the 2023 season.

Walter O’Malley borrows a trumpet from a musician and toots on it at a postgame party at the Hilton Hotel to celebrate the Dodgers’ 1959 World Series title in Chicago on October 8. The Dodgers defeated the “Go-Go” White Sox, four games to two, winning the final game in Comiskey Park, 9-3.

L.A. Dodgers A Hit

While the Dodgers struggled in 1958 making the transition to an unfamiliar environment in Los Angeles, the next season they made a 180-degree turn. The Dodgers tied with the Milwaukee Braves for the best record in the National League and won two straight games in a best-of-three playoff to win the Pennant and earn the right to play the Chicago White Sox in the World Series. The Dodgers defeated the White Sox in six games to bring their first World Championship banner to the city and fans of Los Angeles. The L.A. love affair between a team and its fans was cinched and continues to this day.

From the day they arrived in Los Angeles, O’Malley realized the importance of the diverse marketplace in which the Dodgers played. Long before other sports teams placed games on radio in multiple languages, O’Malley’s Dodgers were available in Spanish beginning in 1954 on WHOM Radio in New York. In Los Angeles starting in 1958, the games were first re-created and then in the mid-1970s, the broadcasters traveled to all road games. English-language radio, with the brilliant and fan-favorite Vin Scully and his long-time broadcast partner Jerry Doggett, grew to immense proportions, initially in the Coliseum and later at Dodger Stadium. Scully’s unparalleled descriptions captured the feel and excitement of each game, providing a storyline that kept fans glued to their transistor radios. More and more women became fans of the Dodgers in Los Angeles and brought their radios with them to the ballpark. Popular Spanish-language broadcaster Jaime Jarrin arrived on the scene in 1959 and retired after the 2022 season and postseason having completed 64 seasons, expanding the interest and listenership in the Latino market to record numbers. He, like Scully before him, was named recipient of the Ford C. Frick Award winner in Baseball’s Hall of Fame. Two Hall of Famers off the field and many more on it are a testament to O’Malley’s extraordinary management skills and knack for identifying quality talent.

In 1965, O’Malley’s coaches included an African-American, Jim Gilliam, and a Cuban, Preston Gomez. When Black Dodger players were precluded from playing golf at the two private clubs in Vero Beach, Florida during Spring Training, O’Malley privately built two golf courses (the first was a 9-hole built in 1965 and the second 18-hole opened in 1972) on Dodgertown property.

To O’Malley, an employee’s ability to give it his all and to do his job properly were the important factors in hiring. Ability also led to stability, a hallmark of O’Malley’s Dodger organization. O’Malley had just two managers, Hall of Famers Walter Alston and Tommy Lasorda, from 1954-79. He had three General Managers — E.J. “Buzzie” Bavasi, Fresco Thompson and Al Campanis — during that period, as well. And only two farm directors, Thompson and William P. Schweppe. And two scouting directors, Campanis and Ben Wade, also. Loyalty, dedication and hard work meant something. O’Malley did not replace managers, even when pressured by outside sources, because it was his opinion that, if the team did not compete successfully, it was an entire organizational breakdown and the blame should not be shouldered by the manager alone.

Fans Top Priority

The fans were a large part of his concern on a daily basis. He and his entire organization were committed to a traditional baseball presentation, always making the game the star, with a family-friendly environment at comfortable, safe and clean Dodger Stadium. All Dodger executives, staff and game-day employees understood the policy of serving the fans and were responsive to their needs. Every phone call and letter was answered. O’Malley read and answered every letter he received with help from his able secretary Edith Monak, who worked with him for over 40 years. He talked with fans both at Dodger Stadium and elsewhere to feel the pulse of how his organization was being run and accepted. O’Malley sent regular year-round communications to his season, group and individual mail order ticket purchasers, including the popular Line Drives newsletter.

He also held the line on ticket prices, making Dodger baseball affordable to families. For 18 seasons, ticket prices ranging from 75 cents to $3.50 remained unchanged, earning Dodger Stadium an extraordinary reputation as a place for a first-rate, inexpensive family outing. The Dodgers set records for attendance, breaking the Major League record in 1962 with 2,755,184. The Milwaukee Braves had gone over the two million barrier for four straight seasons in their new ballpark from 1954-57, after moving from Boston in 1953. The Dodgers would become the first Major League Baseball team to top the three million mark in attendance in 1978.

In 1963, 1965 and 1966, the Dodgers returned to the World Series with the likes of Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale on the mound and hitters like Tommy Davis, Willie Davis, Maury Wills and Ron Fairly leading the way.

As Walter O’Malley developed, built and maintained spring training headquarters at Dodgertown in Vero Beach, FL, the contrast in this 1972 photo is striking in the old barracks used originally in World War II on the U.S. Naval Air Station and the 90 modern accommodations used to house players, staff, guests and media.

Photo courtesy of Indian River County Historical Society, Inc.

Walter O’Malley selected two Dodger Managers — Walter Alston (right) and Tommy Lasorda — who would ultimately take their rightful place in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Alston managed the Dodgers for 23 seasons and won four World Series titles (1955, 1959, 1963 and 1965), while Lasorda managed for 20 seasons and won two World Championships (1981 and 1988).

Copyright © Los Angeles Dodgers, Inc.

It was an exciting era for O’Malley and the Dodgers in their new stadium as they enjoyed success on the field, winning the World Series in 1963 (taking four straight games from the New York Yankees) and 1965 (defeating the Minnesota Twins in seven games), before losing in four straight games to Baltimore in the 1966 Fall Classic. On the Dodgers’ return goodwill trip to Japan after the 1966 World Series, O’Malley was presented with the Third Class Order of the Sacred Treasure Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon award as conferred by Emperor Hirohito from the government of Japan. The high honor was in recognition of O’Malley’s work in promoting friendly relations with Japan through baseball. Director General Kiyosi Mori of Prime Minister Eisaku Sato’s office made the presentation in Tokyo on the tour on November 15.

O’Malley advanced Dodgertown to modern state-of-the-art villas in 1972, replacing the old Naval barracks and continued to improve the finest spring training facility with a new building housing clubhouses, dining room, medical offices, working press room, radio studio, photo darkroom and equipment storage areas in 1974.

Team Success

The Dodgers were teeming with some of the game’s most significant players in O’Malley’s era, including Hall of Famers Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, Gil Hodges, Duke Snider, Roy Campanella, Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale and Don Sutton. The baton was passed to the next generation, as the famous infield of Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Bill Russell and Ron Cey, all raised in the Dodger player development system, guided the team to another successful decade. Manager Alston retired and was succeeded by popular Lasorda on September 29, 1976. Lasorda would be a stable figure in the Dodger dugout for 20 years. Both Alston and Lasorda entered the Baseball Hall of Fame for their success.

Walter O’Malley and his son Peter, who became club President on March 17, 1970, teamed for 48 years to lead the Dodger organization to attendance records, six World Championships and international prominence.

O’Malley’s Dodgers finished either first or second place in 12 of 19 seasons that he was at the helm (1951-69), including eight N.L. Pennants in 1952, 1953, 1955, 1956, 1959, 1963, 1965 and 1966. The Dodgers won World Championships in 1955, 1959, 1963 and 1965 under O’Malley. During O’Malley’s presidency, the Dodgers had the best record in the N.L., played in the most World Series for a N.L. team, and won the most World Championships by a N.L. team. On March 17, 1970, O’Malley’s son Peter was named President of the Dodgers, a position he held for the next 28 years, winning the World Series in 1981 and 1988. From 1970 until August 1979, Walter O’Malley would serve the Dodgers as Chairman of the Board, continuing to guide the path of Major League Baseball through his work on the Executive Council, besides his tremendous outreach to the greater Southland community and his involvement with numerous charities.

Walter O’Malley wears the Third Class Order of the Sacred Treasure Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon award presented to him by the government of Japan, as conferred by Emperor Hirohito, for promoting friendly relations with Japan through baseball. The presentation was held on Nov. 15, 1966 at the Prime Minister’s office while the Dodgers were concluding their second Goodwill Tour to Japan in a decade under O’Malley.

Mrs. Mallie Robinson, the mother of Hall of Fame Dodger infielder Jackie Robinson, presents Walter O’Malley with the George Washington Carver Supreme Award of Merit for “contributions to sports, better race relations and human welfare” in 1959. University of Southern California President Rufus Von KleinSmid is in the middle.

Copyright © Los Angeles Dodgers, Inc.

The Dodgers made World Series appearances again in 1974, 1977 and 1978. In 1979, the Dodgers signed a young left-handed pitcher who would enthrall the hearts and minds of their fans in a magical 1981 season. For years, O’Malley had asked his scouts to find a Mexican player to appeal to the growing Latino fan base in Los Angeles. When it finally happened, they certainly got more than they realized as Fernando Valenzuela, from a tiny village in Mexico, became larger than life in Los Angeles, the United States and a national hero in his home country. Unfortunately, O’Malley would never see the results of this diamond in the rough. Also in June 1979, the Dodgers scouted and signed another fine young pitcher by the name of Orel Hershiser, who would, years later, make headlines for his heroics on the mound.

And so it was that O’Malley dined with world leaders, was honored by Pope Paul VI, received the B’nai B’rith “Man of the Year” award, the George Washington Carver Supreme Award of Merit for “contributions to sports, better race relations and human welfare” and the Silver Beaver Medal by the Boy Scouts. A not-so-complicated man, Walter O’Malley loved life and his family, a wide circle of friends, cooking for everyone, a good game of poker, an even better cigar, cultivating orchids in his greenhouse and most of all, baseball.

Kay O’Malley spent many a pleasant day at Dodger Stadium, with her husband Walter, their two children Terry and Peter and grandchildren. Kay was active as a community volunteer and, in 1971, received recognition as Los Angeles Times’ Woman of the Year.

First Lady of Dodgers

On July 12, 1979, the First Lady of the Dodgers, Kay Hanson O’Malley passed away. The compassionate and loyal Dodger fan had seen so much in her time. Among them, her husband’s achievement as a student, communicator, leader, sportsman, businessman, innovator, visionary, pioneer and family man. She had achieved a great deal herself, as a loving and dedicated wife, mother of two children, grandmother of 12, community volunteer, recognition as Los Angeles Times’ Woman of the Year in 1971 and the ability to continue on and not let her impairment stop her from living a full and exciting life. A true fan of baseball, she kept score for games both at home and on the road. To honor Kay and her affection for the organization, the Dodgers named two team-owned airplanes used for transporting the players for her — the Kay O’, a 1962 Lockheed Electra and the Kay O’II, a 1971 Boeing 720-B Fan Jet.

A visionary and business leader, Walter O’Malley works in his office in Dodger Stadium. O’Malley served as Dodger President from Oct. 26, 1950 through March 17, 1970, when he moved to team Chairman of the Board until his passing on Aug. 9, 1979.

Twenty-eight days later, Walter O’Malley followed the great love of his life, passing away at the age of 75.

Recognition and sympathy poured in from throughout the country and around the world in honor of O’Malley. In Japan, the Tokyo Giants held a moment of silence and “prayed for the repose of O’Malley’s soul” prior to a game with the Taiyo Whales. The Dodgers and their fans also held a moment of silence, with the flags at the house that he built, Dodger Stadium, flying at half mast in his honor. Tributes and kind words were written and spoken by countless friends, colleagues, fans and media members.

The Tokyo Yomiuri Giants team lines up for a moment of silence for Walter O’Malley, following the passing of the Dodger President on Aug. 9, 1979 prior to a game with the Taiyo Whales on Aug. 12, 1979. O’Malley and the Giants established and maintained friendly relations for more than 20 years. The Giants’ team visited the Dodgertown spring training site on four occasions (1961, 1967, 1971 and 1975), while their manager and two players trained there in 1957.

A scoreboard in Tokyo for the Yomiuri Giants’ game asks fans and players to “pray for the repose of O’Malley’s soul” prior to a game with the Taiyo Whales on Aug. 12, 1979, following his passing on Aug. 9.

Former Los Angeles Times syndicated columnist Jim Murray wrote: “O’Malley belongs in the Hall of Fame as surely as Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb and certainly Judge Landis. He made more people rich, quicker than the gold strike of the 49ers who beat him west by only a century. Ted Williams might have had the vision to see a ball curving 60 feet ahead, but Walter O’Malley had the vision to see three decades ahead.

“...can anyone deny that what Walter O’Malley did served baseball — if not, indeed, saved baseball? There are now — count ‘em — six major league franchises on the West Coast and two in Texas, where there were none before. O’Malley built a Taj Mahal of a ballpark, setting the tone for subsequent edifices. He brought the game kicking and screaming into the 20th Century.” Jim Murray, Columnist, Sports, Los Angeles Times, August 10, 1979