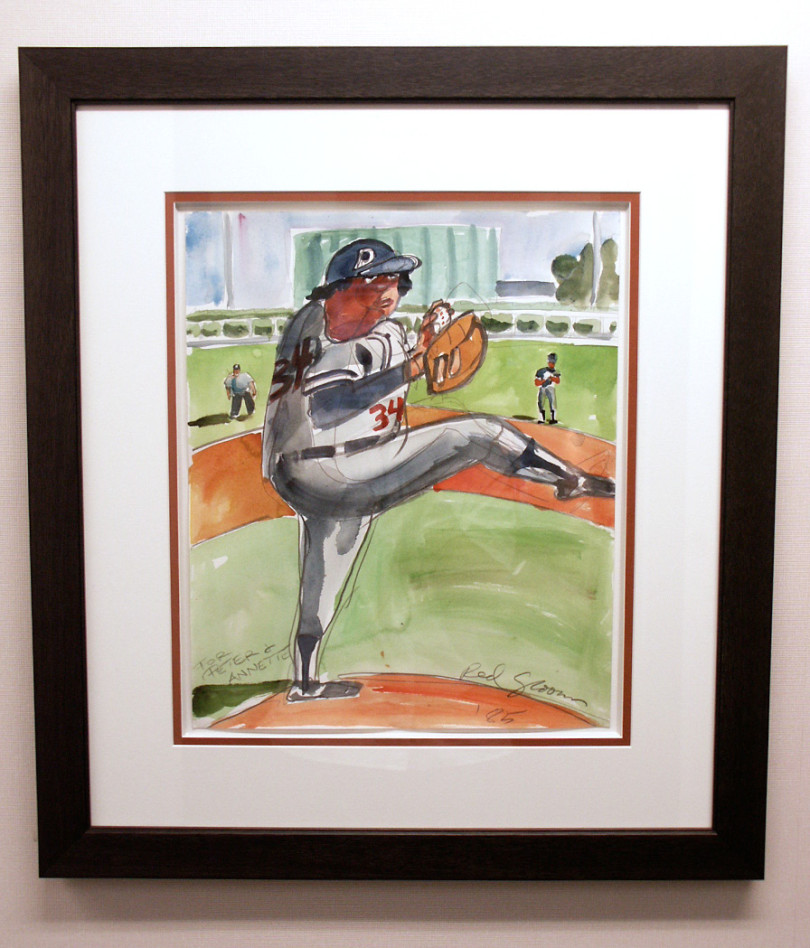

Watercolor painting of Fernando Valenzuela by colorful pop artist Red Grooms in 1985. Charles Bronfman, owner of the Montreal Expos commissioned Grooms for artwork during Spring Training. Valenzuela was pitching for the Dodgers at West Palm Beach Municipal Stadium and Grooms thought he was a great subject. Bronfman then made a gift of the original painting to Dodger President Peter O'Malley and his wife Annette.

The Year of Fernando

By Robert Schweppe

“Unbelievable! I can’t believe it! It is the most puzzling, wonderful, rewarding thing I think we’ve seen in baseball in many, many years!...He is the talk of the baseball world in English, in Spanish, and any other language that’s close at hand….”

Broadcaster Vin Scully, after Fernando Valenzuela shutout the New York Mets in Shea Stadium, May 8, 1981

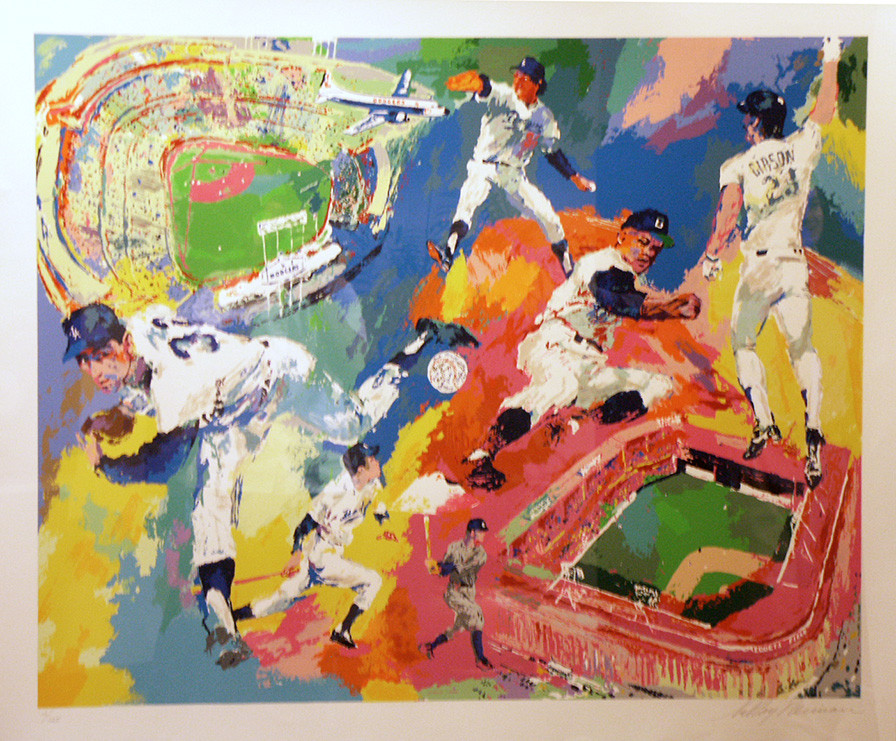

A 1990 serigraph of the painting by renowned sports artist LeRoy Neiman to celebrate the 100th Anniversary of the Dodger organization. The internationally celebrated artist depicts in his impressionistic work Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles and Ebbets Field in Brooklyn in the top and bottom corners. Neiman also stylized Dodger icons from the top as shown by Fernando Valenzuela, Jackie Robinson, Kirk Gibson hitting his 1988 World Series home run, Zack Wheat, Duke Snider, and Sandy Koufax.

Fernando will always have one name icon status.

The 1981 World Championship Los Angeles Dodgers celebrated their 40th reunion at Dodger Stadium on July 25, 2021 as guests of the Dodger organization. Returning players wore a Dodger uniform top and were introduced one at a time. After most of the players were introduced, the public address announcer began his introduction for the last Dodger to be recognized.

Long before the P.A. announcer finished his biography and before the name was said, fans were already rising and clapping. The introduction finished with a standing ovation for the man who won eight straight games at the start of the season, five of them shutouts, won two elimination games in the postseason and pitched a monumental complete Game 3 win in the 1981 World Series as the Dodgers went on their way to the World Championship.

He only needs his first name, Fernando, to be recognized as Fernando Valenzuela.

People who cheered him on that year as 10-year-old youngsters are in their 50s now. We’re all older now, but just the name Fernando brings a warmth to all of us still.

The 1981 season of “Fernandomania” still resonates, but how Fernando became Fernando,” has its own story. And, in a real way, demonstrated the Los Angeles Dodger bold methodology of scouting, signing and developing talent.

Valenzuela’s first professional contract was signed in 1977 when he was 16. He pitched for the Guanajuato team in the Mexican Central League in 1978. It was there he was first scouted by Dodger scout Corito Varona, who had Mexico as his scouting territory. Varona wrote a favorable report on Valenzuela’s ability. This report by Varona prompted Dodger scout Mike Brito to see Valenzuela pitch in person. Brito’s report complements Varona’s and that is told to Dodger Vice President Al Campanis.

Campanis did his own due diligence and went to see the 19-year-old pitch in Mexico. He agreed with the two scouts this was a pitcher they wanted to acquire. However, Valenzuela was not a free agent. He was under contract to the Puebla club in the Mexican League in 1979. Word was getting out on Fernando’s ability. The Dodgers had to move quickly to sign him. Campanis knew the final decision to acquire Valenzuela did not come from him, but only from Dodger President Peter O’Malley.

The price tag was steep. The final sale price approximated $120,000, an amount that ranked with the highest bonus amounts paid to first round choices in the 1979 Free Agent Draft. The Dodger President, trusting his front office and scouts, made the final call and approved the acquisition. Valenzuela signed a minor league contract and then reported to the Dodgers’ California League team in Lodi.

And Fernando’s story takes another turn. When Valenzuela was first acquired, he did not throw a screwball. He had a good overhand curve, but a below average fastball. He pitched well in Lodi with a 1.13 ERA in 24 innings. It is there in Lodi that Dodger scout Ron King, living in Sacramento and covering the California League saw Valenzuela pitch. King, a shrewd judge of talent who drafted and signed Steve Sax, wrote Valenzuela needed another pitch, preferably a screwball, to be successful at higher levels. Brito had stated the same thing to Campanis to recommend Fernando learn to throw a screwball.

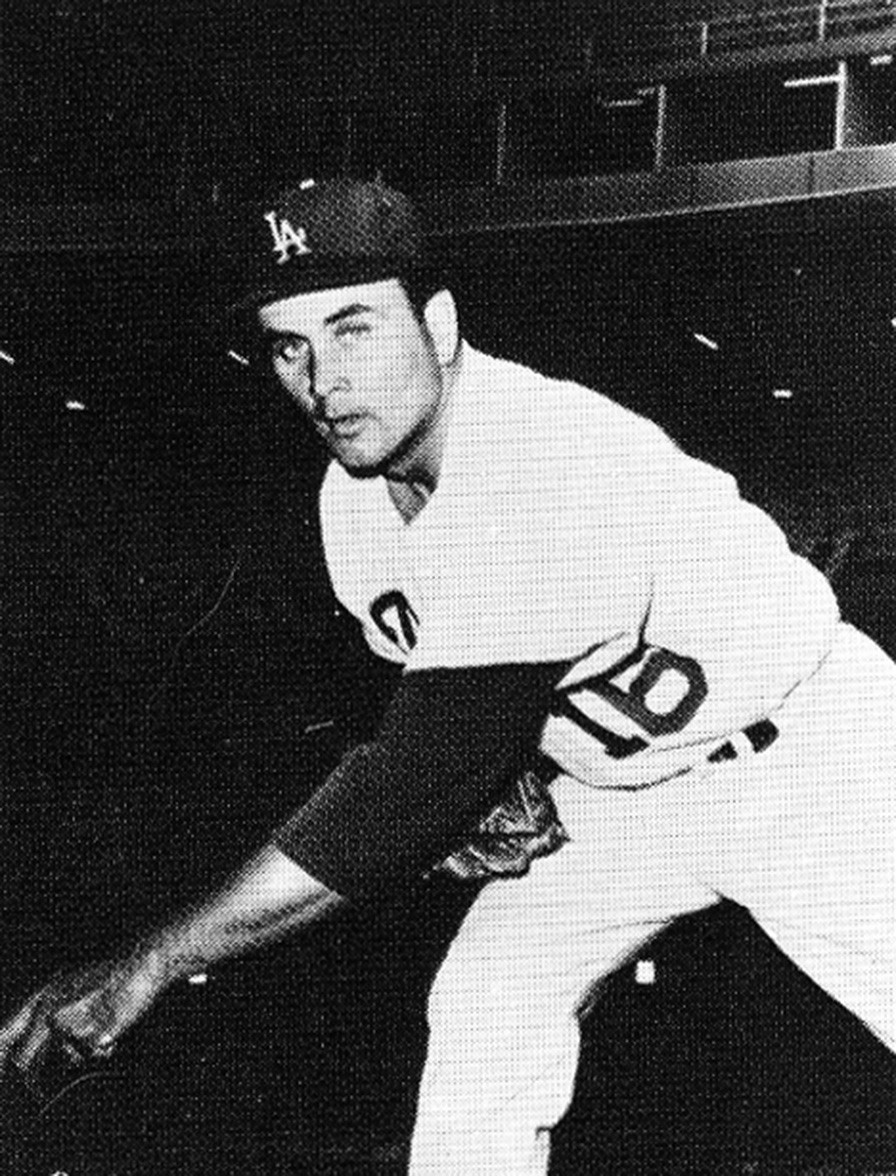

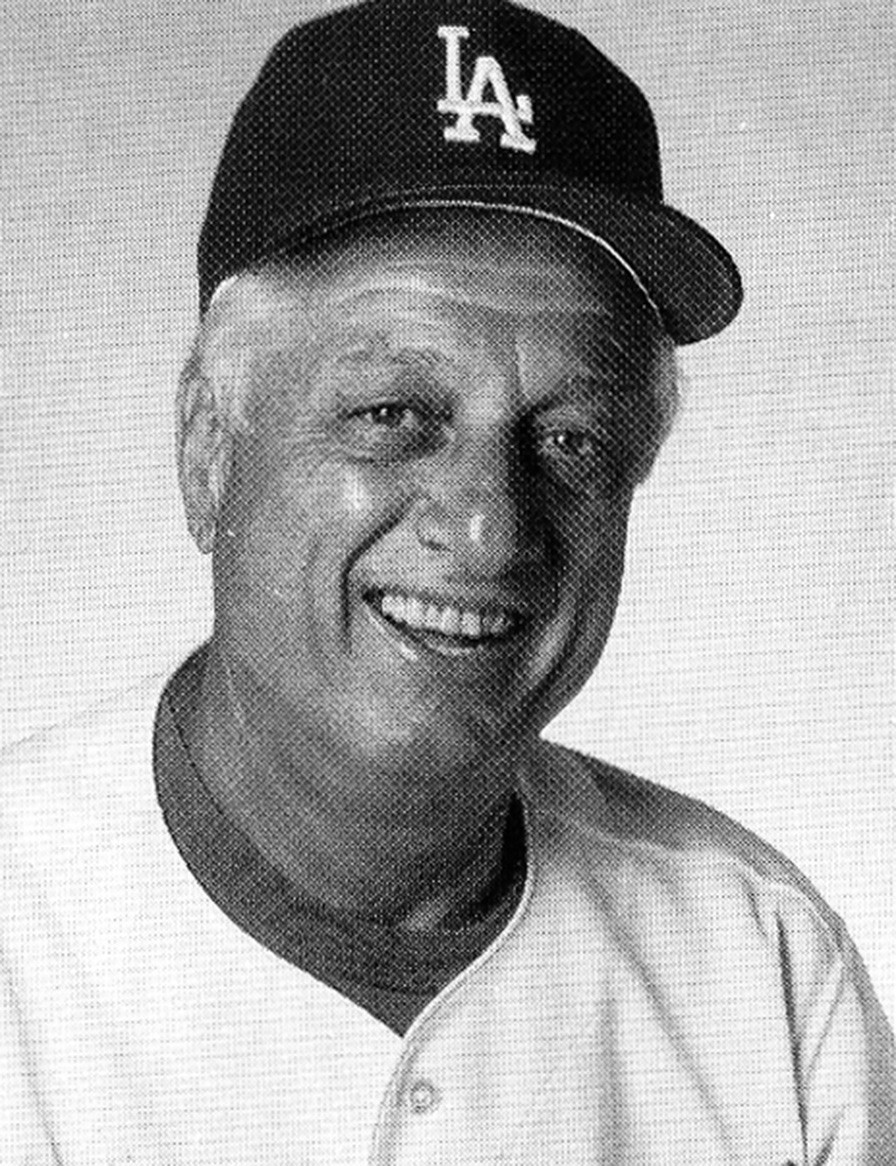

Dodger pitcher Ron Perranoski, 1961-1967; 1972; Dodger pitching coach 1981-1994. Perranoski was Fernando Valenzuela’s pitching coach during his rookie season of 1981 through 1990.

Those scouting reports prompted a discussion by the scouting and minor league player development staff that included then minor league pitching coordinator Ron Perranoski. It was decided Valenzuela would learn a screwball and the lessons would take place for Valenzuela in the Arizona Instructional League.

And the Fernando story takes another turn. Not many pitching coaches teach the screwball. The motion is unusual to throw, hard to control and it takes time and patience for a pitcher to learn a new pitch while he’s still trying to get hitters out. Scout Brito had signed Robert (Babo) Castillo after he pitched for Lincoln High School in Los Angeles and Los Angeles Valley College. Unusual for a right-hand pitcher, Castillo threw a consistent and an above average screwball. Instruction began by Castillo for Valenzuela in the fall of 1979 in Arizona.

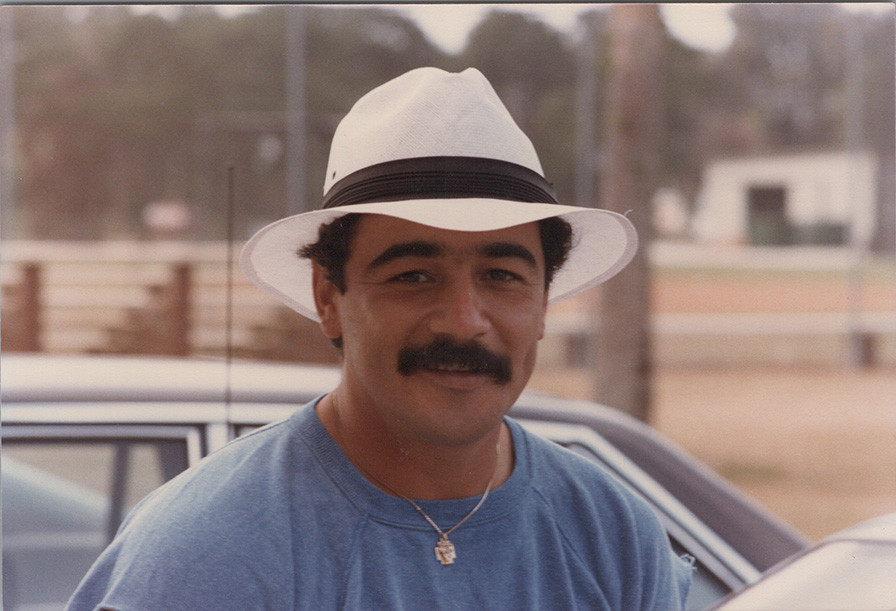

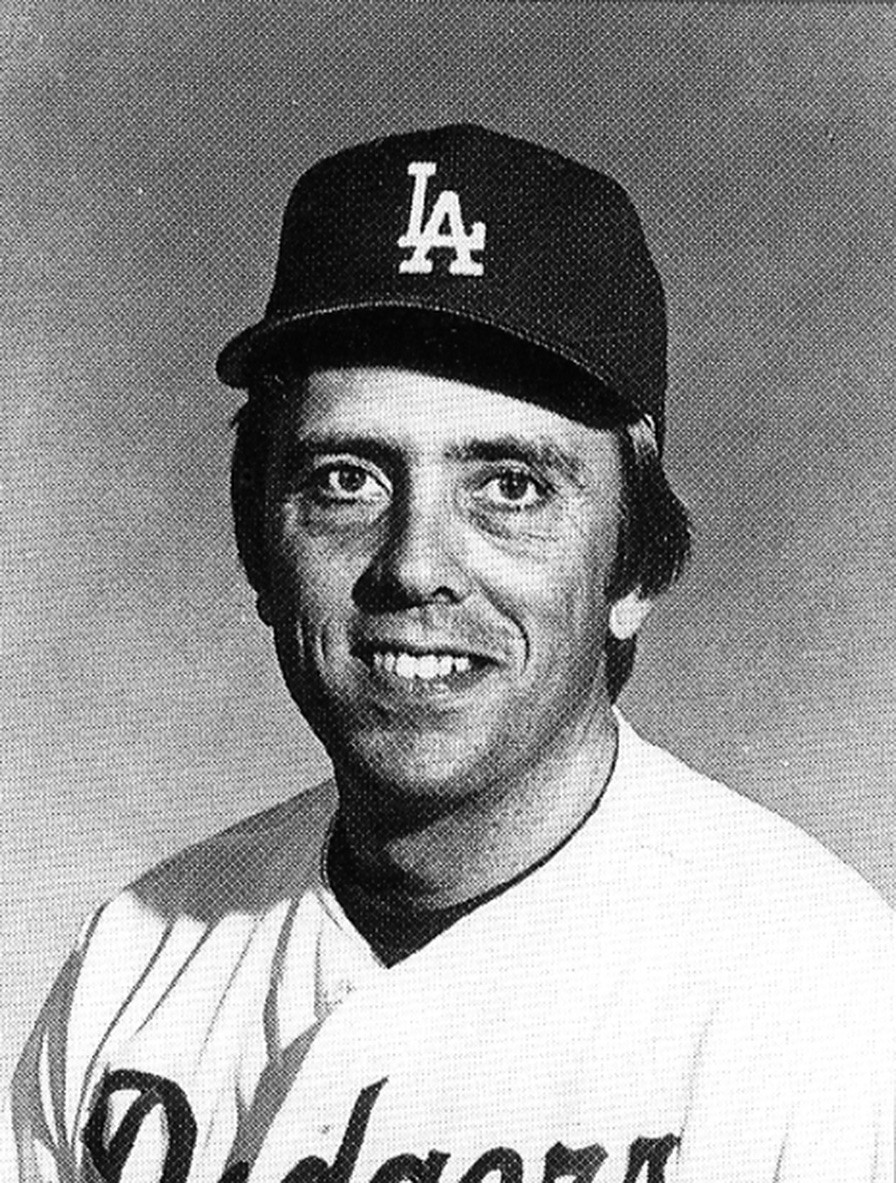

Dodger pitcher Bobby Castillo, 1977-1981 and 1985. He taught Fernando Valenzuela how to throw a screwball that helped to make Valenzuela one of the top pitchers in the 1980s.

The next season, Valenzuela began to throw the unusual pitch. At the age of 19, he was a starting pitcher for the San Antonio Dodgers in the Texas League, two steps below the major leagues. The Texas League is a hitter’s league where the ball travels well and pitchers are still learning their craft. In the first half of the season, Valenzuela pitched decently. By the middle of July, his ERA was 4.34 as he was learning his new pitch.

The screwball has been called a “reverse curve.” When thrown by a left-hand pitcher, the screwball breaks away from right hand hitters and into left hand hitters. When a hitter expects a pitch to be in one dimension and the pitch moves to another, it’s a swing and a miss. Couple that by throwing two screwballs, one at regular motion and one at off-speed, and hitters are way off balance. Adding the extra pitches made his fastball more effective because hitters looking screwball have no chance to adjust to the fastball.

Valenzuela had his doubts about throwing a screwball in competition. In 2011, he told the Los Angeles Times, “The first half of the season, it wasn’t going that well…I said, ‘I don’t want to throw it (the screwball) anymore. I want to go back to what I do.’ They (the ball club) told me, ‘No. We don’t care about your record. We don’t care how many games you win. We want you to keep practicing it.’ By the second half, it was a lot better. By then, I had good rotation on it and good control.”

Pitching instructor Perranoski told Steve Wulf of Sports Illustrated magazine in 1981, “I saw Fernando three times last year (in San Antonio)… The first time he was getting away with some mistakes. The second time he was making fewer mistakes. The third time it was like watching a great horse in his last workout before the Kentucky Derby.”

With Perranoski’s help to find a consistent release point and encouragement to continue throwing the screwball in all situations, Valenzuela became lights out Fernando. In 62 innings from mid-July to the Texas League playoffs, Valenzuela allowed six earned runs (0.87 ERA) and struck out 78. He did not allow a run in his last 35 Texas League innings. For his efforts, the big club felt he was ready to pitch in the major leagues and he reported to the Dodgers. This wasn’t any usual kind of season. The Dodgers were in a heated pennant race with the Houston Astros and the Cincinnati Reds and every game was going to count.

The Dodgers had seen enough of Fernando to think he could pitch in the big leagues. However, his role was to “mop-up.” He was an extra left-hand pitcher in the bullpen. His major league debut in Atlanta on September 15, 1980 was two innings with two unearned runs scored in a 9-0 loss.

Tommy Lasorda managed the Dodgers from 1977-1996, when he retired to become a Dodger Vice President. Lasorda managed Fernando Valenzuela from 1980-1990. Lasorda’s Dodger clubs won 1,599 games in 20 seasons and World Championships in 1981 and 1988. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1997.

He wasn’t mopping up long. Within the next 10 days, Manager Tom Lasorda was using him often in significant spots and Fernando was getting outs and the opposition wasn’t scoring runs. He pitched out of jams; he retired hitters easily. October 3rd, 1980, the Dodgers faced three elimination games in a weekend series against the Houston Astros. Lose one game, and the Astros win the 1980 Western Division title.

Trailing 2-1 in the ninth inning in the first game of the series, Lasorda called on Valenzuela to keep the game close. He blanked them in the top half of the ninth inning and the Dodgers rallied with two outs in their half to tie the game. Lasorda sent Valenzuela out to pitch the 10th inning, he kept Houston scoreless, and the Dodgers won the game on Joe Ferguson’s home run. Jerry Reuss stopped the Astros on Saturday, 2-1, putting the final game of the regular season. The Dodgers had to win to force a one-game playoff or go home.

On the final day of the regular season, October 5th, Lasorda again went to Valenzuela to keep the game in check. The Dodgers trailed 3-1, but again he kept the Astros scoreless in the sixth and seventh innings. Ron Cey won the game on a two-run home run in the eighth inning and the Astros and Dodgers were tied after 162 regular season games.

The Astros won the 1980 Western Division championship the next day in a playoff game. He had pitched 17.2 innings without allowing an earned run.

Publicity Director Steve Brener was confident of Valenzuela’s future. He placed Fernando’s photo on the back of the 1981 media guide, a rare honor for a young pitcher who had turned 20 years old on November 1st, 1980. And in the 1981 Spring Training season, the consensus by those who counted was Fernando earned a spot in the top-notch starting rotation for the Dodgers, who only had the second-best team ERA in the 1980 season.

The Games That Made Fernando, Fernando

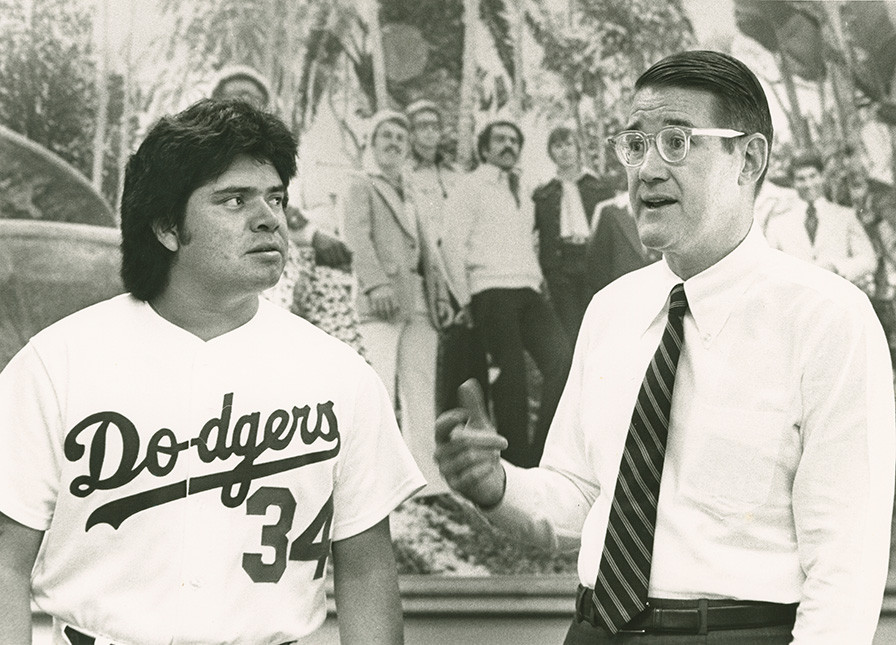

May, 1981, Fernando Valenzuela is with Peter O’Malley, President, Los Angeles Dodgers in O’Malley’s Dodger Stadium office. At the time, “Fernandomania” has begun to captivate and excite baseball fans around the world.

Interviewed by the Los Angeles Daily News in 1990, Peter O’Malley ranked “Fernandomania” in 1981 as the highlight of the best moments in his role as Dodger President. Kevin Modesti, Los Angeles Daily News, April 9, 1990

April 9, 1981, Opening Day vs. Houston Astros at Dodger Stadium

The story of Fernando takes another twist. Jerry Reuss, the Dodger southpaw, who had a superb 1980 season, finishing second in the Cy Young Award, was to be the Dodgers’ Opening Day pitcher. However, the day before Reuss’ start, he strained a leg muscle. Lasorda would have to go with the next man in the rotation. Valenzuela didn’t expect to start Opening Day but had stayed loose by throwing batting practice in the workout before the opener. Pitchers never throw batting practice the day before they start.

Valenzuela took the news the same way he pitched, no nervousness and a desire to get the job done. He became the first Los Angeles Dodger rookie pitcher to start Opening Day, the youngest pitcher to start an Opening Day since Catfish Hunter did for Kansas City in 1966. Valenzuela added to those special credentials as he shutout the Houston Astros, 2-0.

Dodger catcher Mike Scioscia, himself only 22 years old, told Mark Heisler of the Los Angeles Times, “As the game progressed, he (Fernando) got stronger. From the seventh to the ninth inning, he had awesome command of everything. He wasn’t one bit nervous. He’s so cool out there. I don’t think he even broke a sweat.” Bill Virdon, manager of the Houston Astros said, “He may be 20 (years old), but he pitches 30 (as if he was a 30-year-old pitcher).” Columnist Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times wrote, “Fernando came walking out of the Mexican League a year ago sporting the kind of pitching savvy you see only guys who have more labels on their suitcase than the secretary of state.”

And it was only the first game of a scheduled 162. Or so everyone thought.

April 14, San Francisco Giants at Candlestick Park

“Fernandomania” hadn’t started yet. The game was televised on KTTV, Channel 11 to Los Angeles and it was a regular night in San Francisco. Ice cold typical. He allowed four hits and one run with 10 strikeouts. Mark Heisler of the Los Angeles Times estimated the temperature at Candlestick to be 40 degrees, but it felt much colder. The singer of the national anthem kept both of his hands in his pockets as he sang. The Giants scored a two-out run in the eighth inning, Valenzuela’s first major league earned run allowed in 24 innings. Asked about it, he shrugged it off, “I didn’t care they (the Giants) scored. Someday they had to score.”

April 18, San Diego Padres at Jack Murphy Stadium

Mike Scioscia was the catcher for the Dodgers at the age of 22 when Fernando Valenzuela, age 20, pitched his Opening Day shutout in 1981. Scioscia played catcher for the Dodgers from 1980-1992, was a two-time National League All-Star and a member of two World Championship Dodger teams (1981 and 1988). He was considered one of the top catchers in the game for his ability to work with pitchers and call games, as well as his defensive prowess.

Another game televised on KTTV. Fernando started on three days’ rest, not his normal four rest days and threw a shutout 2-0 over San Diego with no walks and 10 strikeouts. Frank Howard, the Padres’ manager, tried to counter Valenzuela’s screwball with a left-hand hitting lineup, but it didn’t matter. Dodger catcher Mike Scioscia interviewed by beat reporters for a statement said, “Same quotes I gave you last time.”

April 22, Houston Astros at the Astrodome

Fernando wins his fourth straight game, third straight on the road and Dodger fans enjoyed it on the telecast in a 1-0 shutout. The Astros had 12 plate appearances with men in scoring position and failed to score a run. As Valenzuela drove in the only run of the game with a single to left field, broadcaster Vin Scully said, “Is there anything this kid can’t do?” In the Astros’ first inning, Terry Puhl was on second base with none out. Valenzuela fielded a bunt attempt, then froze Puhl between second and third base. Without making a throw, he kept Puhl occupied long enough where the kid could tag him out.

April 27, San Francisco Giants at Dodger Stadium

He had won four straight games, three shutouts, and was now coming home to face the Giants. He threw a seven-hit shutout and had three hits of his own, including driving home the first and only run he would need. The capacity crowd cheered loudest when he singled for his RBI in the fourth inning. Dodger coach Manny Mota motioned that it was okay for Valenzuela to tip his helmet to the crowd for his ovation. When he fanned Jim Wohlford for the final out, Scully said, “It is incredible! It is fantastic! It is Fernando Valenzuela! He’s done something I can’t believe anybody has ever done or ever will do!” As a battery of television lights followed him off the field, Hollywood had a new star.

Valenzuela finished the month of April like no one has before. He was 5-0 with five complete games, four shutouts and a teeny-tiny ERA of 0.20. He hit .438 for the month and he received all the votes for National League Pitcher of the Month.

May 3, Montreal Expos at Olympic Stadium

Valenzuela pitched nine innings, but the Dodgers needed bonus frames to score five runs in the 10th inning and he won his sixth straight game. A sellout crowd in Montreal wanted to see just how good Fernando was and he showed them. He retired 21 consecutive hitters at one point in the game until allowing an eighth inning run. The Los Angeles Times had a news report of the impact of Fernando on television ratings in Los Angeles.

May 8, New York Mets at Shea Stadium

The song says, “If I can make it there (New York), I’ll make it anywhere,” and Valenzuela throws a seven-hit 1-0 shutout over the Mets at Shea Stadium. He had won seven straight games at the start of the season, pitched six complete games in seven starts and his ERA, 0.33 at the start of the game, fell to 0.29. After first baseman Steve Garvey catches a pop fly for the final out of the game, broadcaster Vin Scully said, “Unbelievable! I can’t believe it! It is the most puzzling, wonderful, rewarding thing I think we’ve seen in baseball in many, many years!”

May 14, Montreal Expos at Dodger Stadium

Another sellout crowd at Dodger Stadium welcomed home the return of the ball club and Valenzuela was in another close one. The Dodgers led 2-1 in the ninth inning with two outs and no one on base, but his 8th straight win wasn’t going to come easy. Future Hall of Fame player Andre Dawson homered to tie the game and if the Dodgers didn’t do anything in their home half of the ninth inning, Valenzuela was not likely to pitch the 10th inning. With the game tied, Pedro Guerrero untied it and won it with a solo home run to lead off the 10th inning. Vin Scully said, “There are no words to express what’s going on here!,” and baseball’s greatest wordsmith didn’t even try as the crowd cheered and cheered.

May 17, 1981, reception in Los Angeles for the parents of Fernando Valenzuela. Valenzuela had started the 1981 season with eight straight wins, five of them shutouts. (L-R) Peter O’Malley, Dodger President and his wife Annette; Fred Claire (partial), Dodger Vice President, Public Relations; Carol Claire; unidentified; Dodger broadcaster Jaime Jarrin; Fernando; and (seated), mother of Fernando.

Fernando had won eight straight games, five of them shutouts. Nearly every start was close. But no one in baseball is perfect. On May 18th, the Phillies’ Steve Carlton shutout the Dodgers after Mike Schmidt homered in the first inning and it would be all the runs needed as the Phillies won 4-0. Valenzuela told Mike LIttwin of the Los Angeles Times, “I knew it had to end. I’m not sad. I knew it was going to happen sometime.” Even when Valenzuela lost, he still said the right things.

United States Ambassador to Mexico Jack Gavin stands behind Dodger pitching sensation Fernando Valenzuela who sits in the Ambassador’s chair at the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City. Gavin was an actor and served as Ambassador from 1981-1986. Fernando had completed his remarkable 1981 season as the National League Rookie of the Year and Cy Young Award winner leading the Dodgers to a 1981 World Championship. “Fernandomania” became an international baseball phenomenon and Fernando’s popularity was off the charts. Gavin, circa Fall 1981, adds his own humorous caption at the bottom of the photo he sent to Dodger President Peter O’Malley: “Peter, who is the guy sitting in my chair?”

The winning streak may have been over, but the acclaim wasn’t. On June 8th in the 1981 season, Valenzuela was invited to the White House in Washington D.C. to attend a state luncheon to honor José López Portillo, the President of Mexico. It was a tossup who was the most prominent guest as the 20-year-old left hand pitcher was sought out by photographers and politicians for autographs. John Gavin, the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, graciously served as translator for Valenzuela to best convey his message of appreciation at the luncheon.

The Dodgers were playing well, and they held a lead in first place in the Western Division on June 11th. Valenzuela was on the mound for the Dodgers in St. Louis’ Busch Stadium, but everyone’s mind was as much as on the likelihood of an interruption in the schedule by a player strike as it was on the ballgame. Fernando pitched very well, but the St. Louis Cardinals won 2-1. Their runs scored when George Hendrick of the Cardinals hit a fly ball to right field that couldn’t be caught or knocked down and artificial turf had the ball springing away for an inside-the-park home run. So, the first half ended, the Dodgers a scant 1/2 game in first place in front of the Cincinnati Reds, because the Reds were rained out of a game in April but had not yet made the game up.

There was no Major League Baseball due to a player strike through June, July, and the first part of August. The dispute was finally ended in August and teams returned to play.

Hall of Fame Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, 1969-1984.

There was a condition because of the lengthy interruption that there would be an additional level of playoffs for the Division Championship. Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn ruled teams that had finished in first place in the first part of the season before the strike would automatically qualify for the new level of playoffs. By the smallest of margins in baseball, a half game, the Dodgers knew they would be playing in the first round against the winner of the remainder of the season, and it would be the Houston Astros, the team Valenzuela had shutout on Opening Day.

October 10, Game 4, National League Division Series vs. the Houston Astros at Dodger Stadium

Everything was on the line, especially for the Dodgers. They had lost the first two games in the final inning to the Astros in Houston and faced three straight elimination games. Burt Hooton started for the Dodgers in Game 3 and kept them alive for Game 4 with a 6-1 win.

Valenzuela had pitched superbly for the Dodgers in Game 1 of the series with no decision. The club that had looked to him all year for a big game, got it again from Fernando. Valenzuela was shutting out the Astros while the Astros’ pitcher Vern Ruhle, retired the first 14 Dodgers in the game. In the ninth inning, the Dodgers led 2-0, and the Astros broke through to score a run. With two outs, Valenzuela got All-Star outfielder Jose Cruz to pop out to Mike Scioscia in front of home plate for the final out. Right alongside Scioscia as he caught the final out was Fernando, his glove and left hand outstretched, ready at the post if Scioscia had a bobble.

The Dodgers would win the National League Western Division Series the next day when Jerry Reuss shutout the Astros, 4-0. The Dodgers next would face the Montreal Expos in the National League Championship Series. The Dodgers won Game 1 and looked to be a favorite in Game 2 when Valenzuela was the team starter. But you should never trust the game of baseball. Ray Burris of the Expos was excellent and shutout the Dodgers 3-0 and the series was tied as they went to Montreal.

The Expos won Game 3 for a 2-1 series lead and the Dodgers had their bags packed in the hotel lobby before Game 4, facing their fourth elimination game in postseason. They won 7-1 in Game 4 with the help of Burt Hooton and a two-run home run by Steve Garvey in the eighth inning.

October 19, Game 5, National League Championship Series vs. the Montreal Expos at Olympic Stadium

Game 5 of the National League Championship Series was scheduled for Sunday, but NBC and snow and rain helped to postpone the game. NBC preferred to televise Game 5 in the afternoon after their football coverage was complete, but cold and rainy weather prevented any chance to play and a postponement is made to Monday. The Expos may have been glad to give their Game 5 starter, Ray Burris, another day of rest, but it was also another day of rest for Fernando.

Game 5 was the Dodgers’ fifth elimination game in the postseason. They had to win them all to go to the World Series. Valenzuela allowed a first inning run to the Expos but prevented further scoring by getting Andre Dawson to hit into a double play to take the heart out of a big inning.

Montreal weather was overcast and cold and it took Fernando to drive in the tying run in the fifth inning. The Dodgers had base runners on first and third base and Lasorda signaled he wanted the runner on third base to break for home on contact. Valenzuela got his bat on the ball and hit a grounder to second base and on that gamble by the Dodger manager, he drove in the tying run.

Dodger outfielder Rick Monday,1977-1984. Monday is a Dodger hero. On October 19, 1981, he hit a solo home run in the ninth inning with two outs on a bitterly cold day in Montreal in Game 5 of the 1981 National League Championship Series. The home run gave the Dodgers a 2-1 lead and Bob Welch got the final out as the Dodgers won the National League Pennant and would go on to defeat the New York Yankees for the 1981 World Championship.

The game went into the ninth inning with the score tied. Years later, a documentary based on the 1981 National League Championship Series was titled “Blue Monday,” because the Dodgers defeated the Montreal Expos on a Monday to play in the World Series and the big blow was a two-out ninth inning home run by Rick Monday to give the Dodgers a 2-1 lead.

Valenzuela started the ninth inning and got the first two hitters out, but after consecutive walks, Lasorda went to his bullpen for the final out. Bob Welch got a ground ball out for the save and the Dodgers were on their way to the World Series. Twenty-year-old Fernando had kept them alive on that cold, gray, but no longer dark day in Montreal.

October 23, Game 3 of the 1981 World Series against the New York Yankees at Dodger Stadium

Game 3 was as close as being an elimination game as it could be for the 1981 World Series. The Dodgers lost the first two games in New York to the Yankees, and they were facing long odds if they lost as no team previously had ever come back to win the World Series after losing the first three games. Fernando would be the starting pitcher.

In an interview with Bob Oates of the Los Angeles Times that appeared the morning of Game 3, Dodger President Peter O’Malley said, “I don’t know if anyone has had a more spectacular season than Fernando Valenzuela.” At the end of the interview, Oates asked O’Malley “So why can’t you beat the Yankees?,” as the Yankees had won the 1977 and 1978 World Series over the Dodgers and now led the 1981 World Series two games to none. O’Malley’s confident response was “We’ll beat the Yankees.”

Ron Cey gave Valenzuela a 3-0 lead in the first inning with a home run, but the Yankees made life difficult for Fernando. By the fifth inning, he was trailing in the game, 4-3 and had walked five. After a leadoff double by the Yankees to start the inning, the Dodger bullpen began warming up as Valenzuela’s spot would be fifth in their half of the inning. The Dodgers then rallied and had tied the game and outfielder Reggie Smith was in the on-deck circle to hit for Fernando. A pinch-hitter for Fernando would occur only if Mike Scioscia could give the Dodgers the lead. Scioscia hit into a double play and did not receive an RBI, but it gave the Dodgers the lead and it kept Fernando in the game.

Dodger Vice President Tommy Lasorda displays the special lining of the Dodger logo in his suit jacket.

Dodger Manager Lasorda was asked after the game if he was going to pinch-hit for his starter even with the lead. Lasorda told The Sporting News, “I thought about it, but I said no — this is the Year of Fernando.”

After Valenzuela’s seventh walk to the Yankees in the seventh inning, Lasorda ran to the mound to speak to Valenzuela. Lasorda, fluent in Spanish from his years managing in the winter leagues told Fernando “If you don’t give up another run, we’re going to win this game.” Fernando had pitched in tough spots all season long, but he could be allowed this small measure of doubt in his manager. In English, Fernando responded, “Are you sure?”

With the help of a double play started by Ron Cey at third on a sacrifice bunt attempt in the eighth inning, Valenzuela made it to the ninth inning. Call it whatever you want, determination, desire, courage, backbone, guts, style, character, he retired the Yankees in order in the ninth inning, only the second time he had done that in the game. His pitch count for the game was 149 pitches, staggering even then, impossible today.

Given new life, the Dodgers won the next three World Series games for the 1981 World Championship. After Valenzuela’s noble effort in Game 3, Manager Lasorda told Mark Heisler of the Los Angeles Times, “That was one of the guttiest performances I’ve ever seen a young man do. He was like a championship poker player, bluffing his way through a hand.”

Vin Scully, sports greatest broadcaster ever and ever will be, said of Fernando pitching Game 3 of the 1981 World Series, “Somehow, this was not the best Fernando game. It was his finest.”

Fernando Valenzuela electrified baseball during the 1981 “Fernandomania” season. Selected as the Dodgers’ Opening Day starting pitcher in 1981, he threw a shutout, becoming the first Dodger rookie pitcher to pitch a shutout on Opening Day. From there, he went on to win eight straight decisions and five of them were shutouts becoming one of the most beloved Dodgers of all-time.

Fernando would finish his first major league season elected as the 1981 National League Cy Young Award and National League Rookie of the Year. Fernando married his wife Linda that winter. Later, in life, he became a U.S. citizen on the Dodger Stadium field and a favorite Dodger Spanish radio broadcaster. During the remainder of the O’Malley family ownership of the team, no player ever again was issued his No. 34. On August 11, 2023, Dodger ownership made it official and Fernando’s number was retired and displayed on the “Ring of Honor.”

His first name and his uniform number is still enough to bring cheers from everyone who remembers “the year of Fernando.”