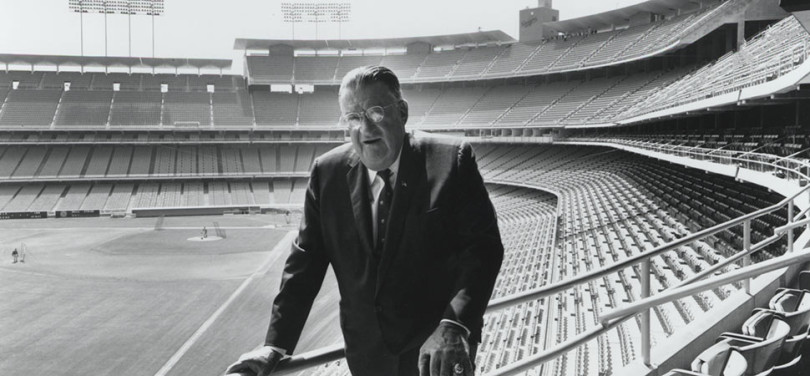

Walter O’Malley outside of his office on the Club Level at Dodger Stadium. O’Malley designed, privately-financed and built Dodger Stadium and is also credited with the westward expansion of Major League Baseball prior to the 1958 season.

Reference Biography: Walter O’Malley

By Brent Shyer

Introduction

One of the most powerful and successful businessmen of his era, or any other generation, Walter Francis O’Malley stamped an indelible mark on the global game of baseball. With his sharp leadership abilities and business acumen, combined with his love of life and keen sense of humor, O’Malley guided his Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers baseball teams to international prominence.

The beauty of Dodger Stadium, the newest jewel of baseball is seen at night in its first decade after Opening Day on April 10, 1962.

His life and career were extraordinary in many ways. O’Malley’s crowning achievements were the important westward expansion of Major League Baseball in 1958 and the building of Dodger Stadium in 1962, which was the first privately-financed ballpark since Yankee Stadium had opened in 1923.

On December 3, 2007, O’Malley was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in its ballot of executives/pioneers. Induction ceremonies were held on July 27, 2008 in Cooperstown, New York. In December 1999, The Sporting News named O’Malley the 11th Most Powerful Person in Sports in the last century, while ABC Sports ranked O’Malley in its Top 10 Most Influential People “off the field” in sports history as voted by the Sports Century panel. But, his good old-fashioned American success story starts when baseball was king in the city where he was born.

In a time when baseball had three New York-based ballclubs — the Yankees, the Giants and the Dodgers — at the height of their popularity, O’Malley understood the importance of creating a unique identity for his team. The Dodgers were hampered by a home stadium that was aging. While Brooklyn’s residents indeed had a long-lasting love affair with “Dem Bums,” the nickname for their appealing Dodgers, the cozy ballpark called Ebbets Field was landlocked in a neighborhood which provided parking for only 700 automobiles.

Ebbets Field provided a cozy atmosphere for Dodger fans in Brooklyn, but the stadium’s age plus limited seating and parking capacities prompted Walter O’Malley’s quest for a new ballpark.

The grandeur of Dodger Stadium, the site of some of baseball’s most memorable and exciting moments through the years.

Barry Howe Photography Copyright © 1992

The automobile was both a curse and a blessing for the Dodger faithful. With construction of new highways and bridges outside of the city, Brooklynites had fled from the confines of their tightly-knit community to the suburbs in those same cars. In the early 1950s, O’Malley saw an immediate need to find land for another ballpark. Certainly, limited parking and no room for growth were not going to provide future success. But, try as he might O’Malley was unsuccessful in convincing the elected and appointed officials to assemble the necessary property for him to build a privately-financed, family-friendly new ballpark in Brooklyn. His determination to build his own stadium, control it and the team that played in it, certainly was bucking the trend. In the 1950s, stadiums such as County Stadium in Milwaukee (1953), Memorial Stadium in Baltimore (1954) and Municipal Stadium in Kansas City (1955) were being built with funding from cities and municipalities, not by ownership.“Take Me Out To The Ballpark” by Josh Leventhal, Page 87, Municipal Stadium in Kansas City was a complete refurbishment of Muehlebach Field and the capacity was nearly doubled with the addition of a second deck

Opening Day at Ebbets Field in 1952 with (l-r) Giants Manager Leo Durocher, Dodger Vice President and General Manager Buzzie Bavasi, President Walter O’Malley and Manager Charlie Dressen.

From the outset, O’Malley felt the Brooklyn faithful deserved a home field that was state-of-the-art, clean and proudly represented the city in which they lived. Ever the visionary, O’Malley had communicated with and later worked with famed architect R. Buckminster Fuller to design a geodesic domed stadium with a retractable roof in the mid-1950s.

Walter O’Malley inspects a geodesic domed stadium model with architect R. Buckminster Fuller at Princeton University in November 1955.

Photo by Wil Blanche. Copyright © 1955. All Rights Reserved.

In O’Malley’s stadium, many new inventions would have captured the imagination of the public, among them a pole-less grandstand permitting an unobstructed view from every seat; a shopping center right on the stadium grounds; electronic ticket sellers which would let patrons choose their own seats from a giant tote board; and even “hanging boxes” to provide 1,500 luxury seats suitable for rental to season ticket holders.

“It was treated facetiously by the press,” said O’Malley. “But why should we treat baseball fans like cattle? I came to the conclusion years ago that we in baseball were losing audience and weren’t doing a damn thing about it. Why should you leave your nice, comfortable, air-conditioned home to go out and sweat in a drafty, dirty, dingy baseball park?”Time Magazine, “Walter in Wonderland,” April 8, 1958

Had the support and enthusiasm for O’Malley’s vision been embraced by city leaders, the Dodgers would have remained in Brooklyn and history could have written a much different script.

An artist’s rendition of the Club Level at the new Dodger Stadium. Patrons on this level also enjoyed the Stadium Club restaurant, which overlooked right field.

Brooklyn, New York — Circa 1952. Ebbets Field, the home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, is visible in the bottom right corner of the photo.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle Photographs—Brooklyn Public Library—Brooklyn Collection

Among the many plans for a ballpark, this blueprint outlined a proposed “Flatbush Stadium,” at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues in Brooklyn.

But, O’Malley was unable to elicit the backing of strong-willed Robert Moses, who was an assistant to New York Mayor Robert Wagner and Commissioner in charge of public use of parks and highways. Moses, who controlled virtually every building project in that era, and the city balked at providing the specific parcel of land at the intersection of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues in Brooklyn which O’Malley preferred. It would have alleviated the parking issue and provided space for a first-class stadium in Brooklyn. The site was just two miles from Ebbets Field and was home to the Long Island Rail Road depot and Fort Greene Meat Market. Transportation-wise, this would have been an ideal location as all of the subway lines and the LIRR converged there. Site studies showed that both the old LIRR terminal and the meat market could have been relocated, even with significant benefits to local residents, including lowering meat prices.O’Malley testimony, transcript of Hearings Before Special Subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives in Connection with Its Study of The Anti-Trust Laws, June 26, 1957, p. 968

The property O’Malley pointed to in Brooklyn required the city to acquire the land through “eminent domain” and Moses refused to do this because he felt that private land should not be condemned for “public use” in this case, citing Title I of the Federal Housing Act. Moses disagreed with the idea of the Dodgers, as a private organization, benefiting from “eminent domain” land. He did not balk at the difficult task of the Dodgers assembling and purchasing their own land in that area and having the city assist with roads and infrastructure. That was all that O’Malley had ever asked for, nothing more or less, but not at vastly inflated prices for acquiring the many properties.

On June 4, 1957, Walter O’Malley appears at a press conference along with (front L-R) New York Mayor Robert Wagner, New York Giants President Horace Stoneham and Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore.

AP Photo

While O’Malley held an open mind to alternate suggestions in Brooklyn, nothing feasible seemed to fall into place. After much deliberation, Moses offered land in Flushing Meadows in the Borough of Queens late in the game in 1957. O’Malley, who had reviewed the possibility of a Queens site three years earlier and felt he was on a wild goose chase, made it clear that a site “five miles or 3,000 miles” outside of Brooklyn was irrelevant, because it still was not in Brooklyn. Other sites were mentioned including “one between a cemetery and Jamaica Bay” according to the Dodger President. O’Malley quickly retorted, “...we weren’t likely to get many customers from either place.”Time Magazine, “Walter In Wonderland,” April 28, 1958 Realizing that Moses had a much different view of the situation and his own political agenda, O’Malley decided to explore all of his options.

In his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York,” Robert A. Caro writes that Moses, “killed, over the efforts of Brooklyn Dodger owner Walter O’Malley, plans for a City Sports Authority that might have kept the Dodgers and Giants in New York, and began happily to plan the housing projects that he had wanted on the sites of the Polo Grounds and Ebbets Field all along;...”Robert A. Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, Alfred A. Knopf Publisher, 1974

The City of New York’s Planning Commission outlined its Master Plan of the Brooklyn Civic and Downtown Area. Walter O’Malley engaged in a steady dialogue with the Commission in hopes of acquiring property for a privately financed ballpark.

Newly-built ballparks with greater seating capacity and more space for parking would attract additional fans. O’Malley only had to look at the success of the Milwaukee Braves, who had recently relocated from Boston, and were playing in a packed new stadium. The Braves’ move in 1953 was the first realignment in the majors since 1903. The Braves, drawing twice as many fans as the Dodgers in their new ballpark, were making a greater profit than the Dodgers, who had been linked to Brooklyn since joining the National League in 1890. Despite attendance of one million a season and loyal fan support, the Dodgers played in a ballpark that was limited to 32,000 capacity.

Attendance chart shows the Milwaukee Braves at Milwaukee County Stadium, opened in 1953, outpacing the Dodgers who were playing at aging Ebbets Field in Brooklyn.

“If we had continued to draw around a million attendance back in Brooklyn while the Braves drew more than 2 million in Milwaukee, they’d have the advantage over us and every team in the league,” O’Malley told Sports Illustrated. “They’d have better scouts, better players, pay bigger bonuses — you’d see it work right down the line. It’s as certain as a lab experiment. Better tools lead to better products.”Robert Shaplen, O’Malley and the Angels, Sports Illustrated, March 24, 1958

Douglas DC-3 (1950-1956). In 1950, the Dodgers acquired a DC-3 from Eastern Air Lines President Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker. The DC-3 replaced the Twin Beechcraft that former Dodger President Branch Rickey used to fly around Florida and to and from New York to Vero Beach, Florida for Spring Training. Bud Holman is visible looking at the plane, standing on the far right.

The West Coast was calling and O’Malley had to listen. San Francisco and Los Angeles were interested in bringing the first major league baseball teams west of Kansas City. The burgeoning commercial airline industry with its affordable jet fares and additional flights allowed teams to make coast-to-coast road trips, which previously had not been available due to the prohibitive expenses and time associated with long distance travel. Trains and buses were the modes of transportation for baseball teams in this period. But, the Dodgers owned their own airplane. This provided the players and staff with comfort and flexibility in traveling. At an August 27, 1952 meeting of the Dodger directors, O’Malley explained that the company plane had flown player and office personnel in and out of Vero Beach, FL for spring training at a cost of $14,442. If commercial transportation had been used for these 31,286 air miles, it would have more than doubled the cost ($30,149). He stated “there is nothing to indicate that the plane is an extravagance.”Dodger Board of Directors Meeting Minutes, August 27, 1952

Dwindling attendance figures at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field underlined Walter O’Malley’s search for a new ballpark. Another factor was the emergence of the Milwaukee Braves, who moved from Boston in 1953 and enjoyed record attendance figures at Milwaukee County Stadium.

AP Photo

It would be the first of five airplanes the Dodgers would own during the innovative O’Malley regime, an investment that not only paid dividends and made him an efficiency expert, but established the Dodger organization as first class in every way.