In 1943, Dodger President Branch Rickey and Dodger counsel Walter O’Malley were on a mission to sign Silvio Garcia, a Cuban of African descent, who was targeted to become the first Black player in Organized Baseball.

The Experiment Before Baseball’s Great Experiment: Silvio Garcia And The Brooklyn Dodgers

By Jerald Podair

On the morning of April 11, 1943, Brooklyn Dodger attorney Walter O’Malley boarded a plane in Miami, Florida, bound for Havana, Cuba, on a mission that he hoped would change not just American baseball history but American history itself. And he almost did. If O’Malley had succeeded, the name Silvio Garcia would be as well-known as that of Jackie Robinson, and possibly even more so. Because Silvio Garcia would have been Jackie Robinson, four years early.

The Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers are generally regarded as America’s most inclusive sports organization, beginning with the debut of Robinson as Major League Baseball’s first 20th century African American player in April 1947. But even before this history-altering event, the Dodgers were prepared to make an offer to another Black player who also would have changed the course of American Civil Rights history.

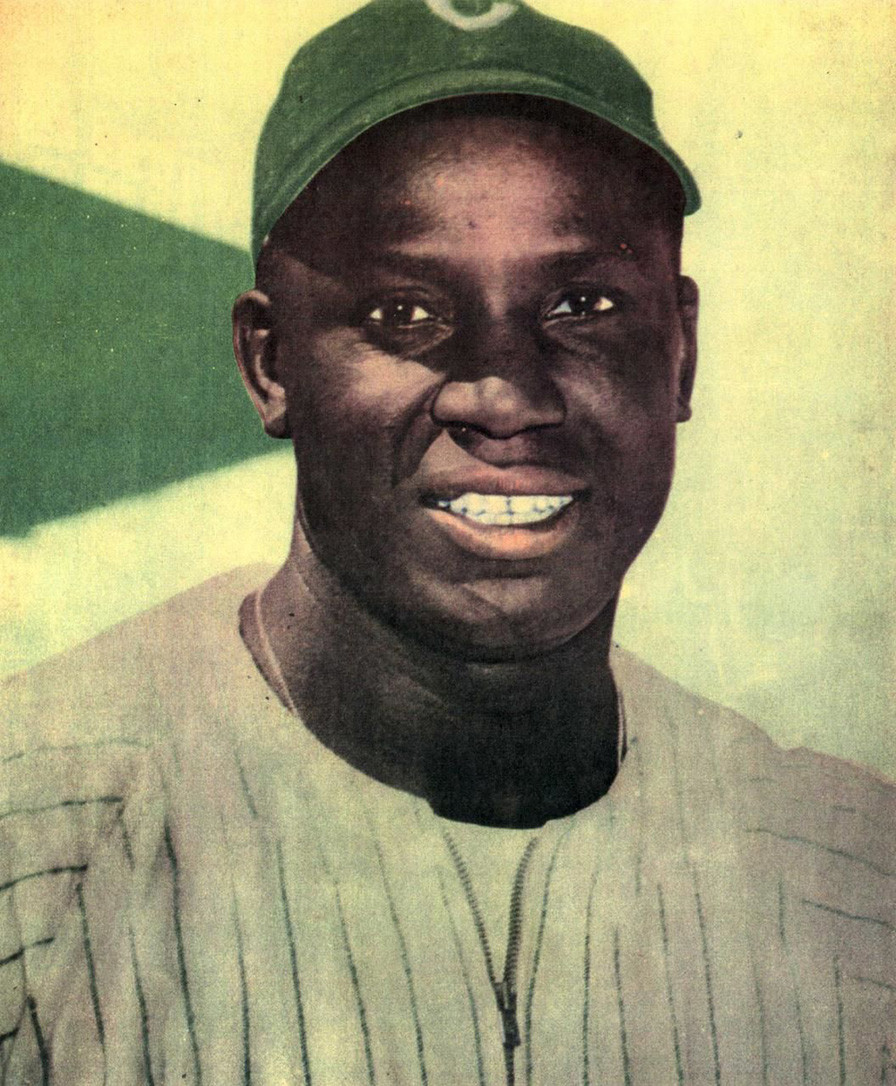

Silvio Garcia was a 6-foot, 195-pound, powerfully built shortstop with RBI power, of whom then-Dodger manager Leo Durocher, a man known for his acerbic bluntness in player evaluations, had gushed, “Marty Marion couldn’t carry his glove.” Given that Marion, nicknamed “Mr. Shortstop,” is regarded as one of the best fielders in baseball history, this was high praise from a demanding critic.

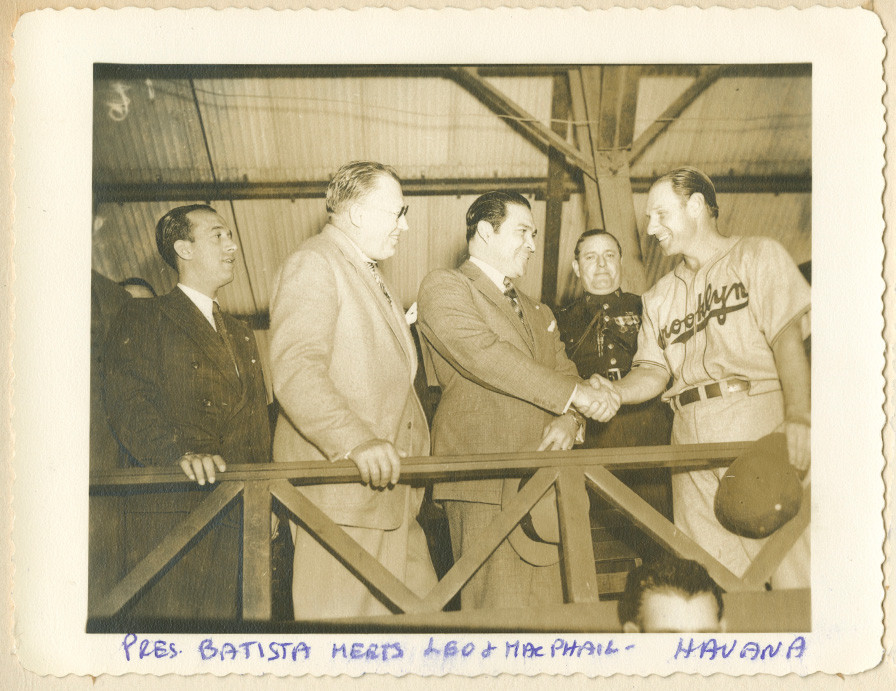

Cuban President Fulgencio Batista shakes hands with Dodger Manager Leo Durocher during Dodger Spring Training in Havana, Cuba circa 1941, while Dodger President Larry MacPhail in light suit looks on.

Photo by Barney Stein

Durocher had seen Garcia hit .381 for a Cuban All-Star team in an exhibition series against the Dodgers in 1942 when the Dodgers took spring training in Havana, Cuba. Durocher recommended Garcia to the new Dodger president, Branch Rickey, when he left the St. Louis Cardinal front office to join Brooklyn later that year. Playing in the Mexican League in 1942, Garcia batted .364 and won the RBI title. He followed up with a .301 average during the 1942-43 Cuban League season.

All this by itself would make Garcia a special major league prospect. But what made him a unique major league prospect was his race. Garcia was a Cuban of African descent, and no Black player had played in the major leagues in the 20th century. While Garcia was not an African American, it is doubtful that would have made much difference to those who were determined, some with public display and others via quiet maneuver, to keep the National Pastime a white man’s sport.

The Dodgers’ interest in Silvio Garcia was motivated by that combination of ambition and idealism of which so much of historic progress in American life is composed. In 1943, the Second World War was siphoning off able-bodied players. When Branch Rickey exchanged St. Louis, a city with many of the vestiges of Jim Crow, for New York, a city at the epicenter of the American Civil Rights Movement, he became part of an organization whose partners were sympathetic to his plans to transform America’s game.

The Dodgers, like every other major league team, faced a wartime labor shortage. How would they find players? One way would be to dive deeply into the high school talent pool. Rickey was already sending hundreds of inquiry questionnaires to secondary school coaches across the country, mining for prospects with the goal of reproducing his vast, numbers-heavy Cardinal farm system in Brooklyn. But he would also look in the Negro Leagues, as well as overseas, at a time when a “gentleman’s agreement” among major league owners not to sign players of color still existed, one that Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis did not challenge. The Brooklyn Dodgers would go where other clubs would not, or dared not, go. As Rickey wrote in his “President’s Report to the Stockholders, Brooklyn National Baseball Club, Inc.,” later in 1943, ”the scouting enterprise now being undertaken by the Brooklyn organization is a pioneer movement more extensive and more thorough than anything that has ever been undertaken by any baseball organization in the past.”

Rickey’s crucial ally in his “pioneer movement” was Walter O’Malley, who would later own the team but who in 1943 served as general counsel and represented the Brooklyn Trust Company, mortgage holder on a portion of the club’s assets, on their Board of Directors. O’Malley became the point man for the Dodgers’ pursuit of Silvio Garcia.

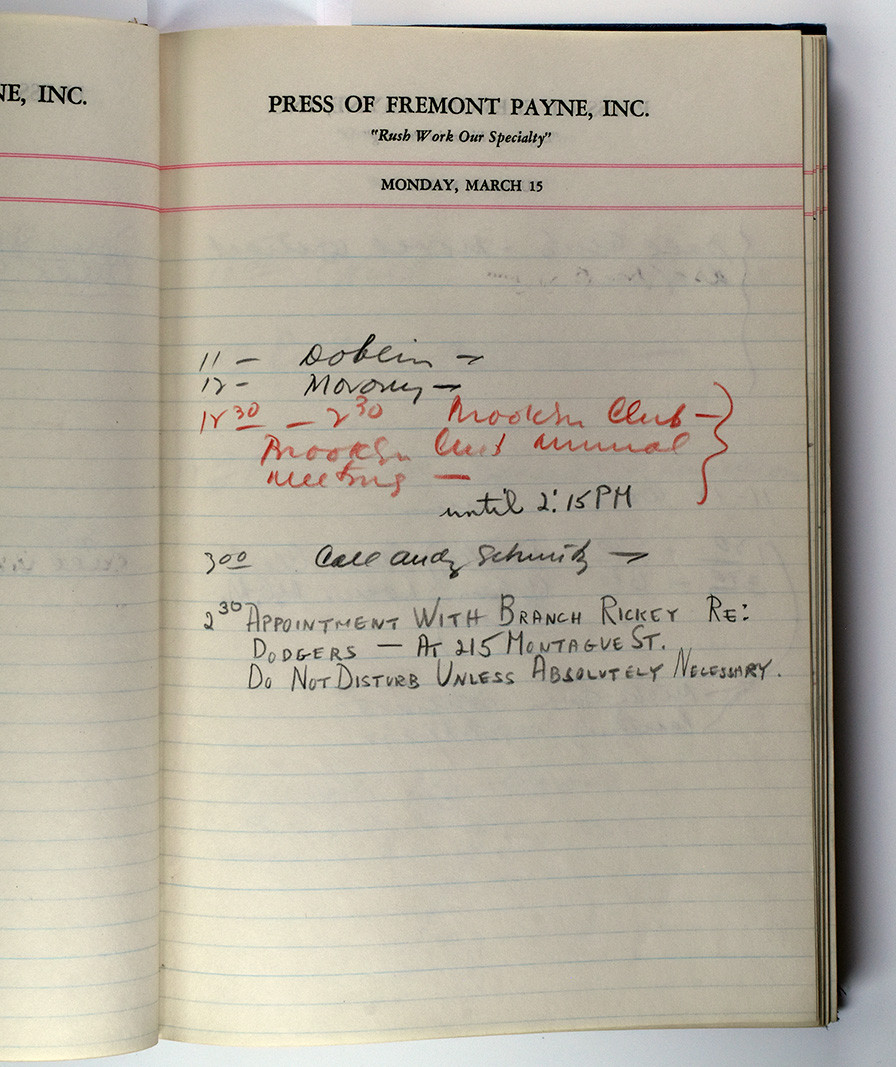

March 15, 1943 is one of the earliest meetings Dodger counsel Walter O’Malley has with Dodger President Branch Rickey. Written in O’Malley’s 1943 appointment book is an emphatic statement and what may lead to a significant change in baseball history up to that time. It is at this meeting that Rickey and O’Malley are believed to have first discussed the ramifications of signing Silvio Garcia, a Cuban of African descent. Over the next few weeks, Rickey and O’Malley met numerous times including on April 3 and April 5 with the Dodger Board of Directors where the two lay out their plans to sign Garcia by having O’Malley travel to Havana.

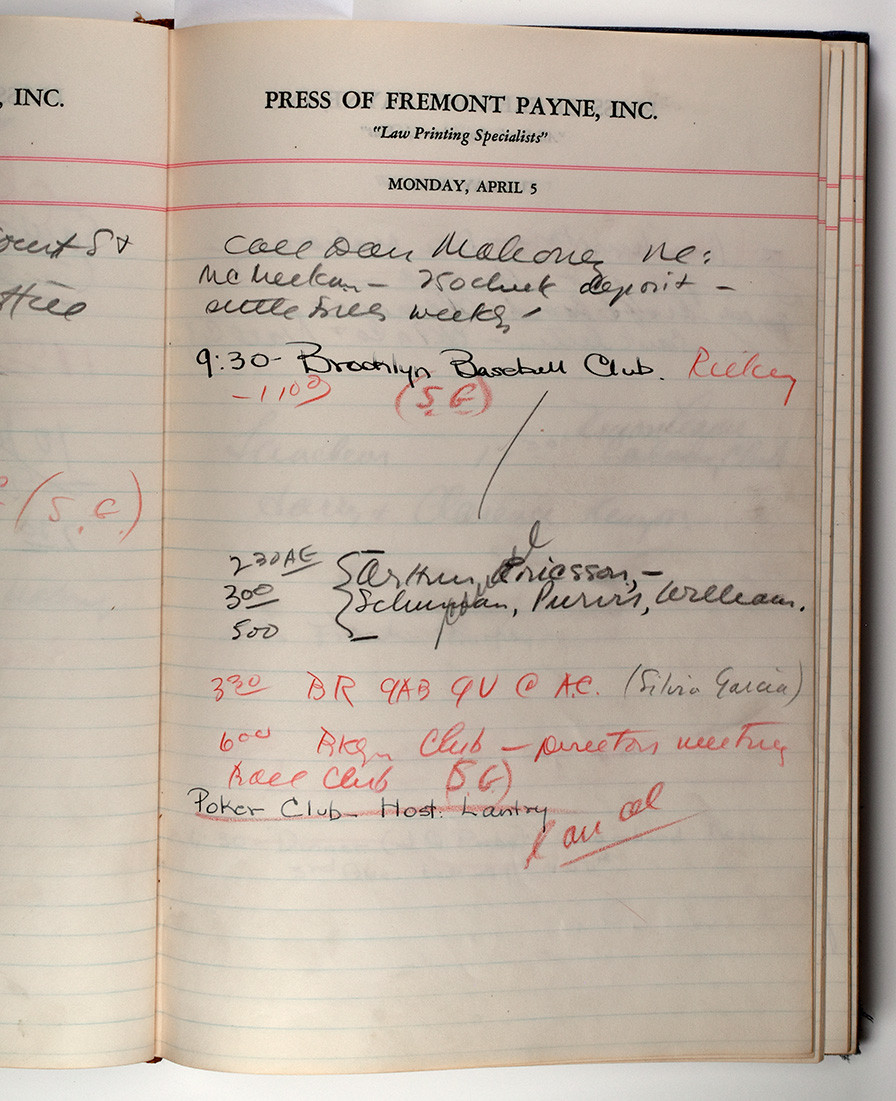

O’Malley’s appointment books for the months of March and April 1943, contain the story of the Garcia plan in shorthand form. They record a series of conferences with Rickey on the subject of “S.G.” or “Silvio Garcia,” culminating in three meetings on April 5, 1943, the last of which included the Dodger Board of Directors, which Rickey and O’Malley informed of their plans to sign Garcia. A formal proposal to proceed with the transaction was then approved.

Entries from Walter O’Malley’s 1943 appointment book on Monday, April 5 detailing Dodger President Branch Rickey’s mission to sign Silvio Garcia in Havana, Cuba. O’Malley met on the topic with Rickey three times on this date regarding S.G. (or Silvio Garcia). The Dodgers were attempting to sign the first Black to an Organized Baseball contract.

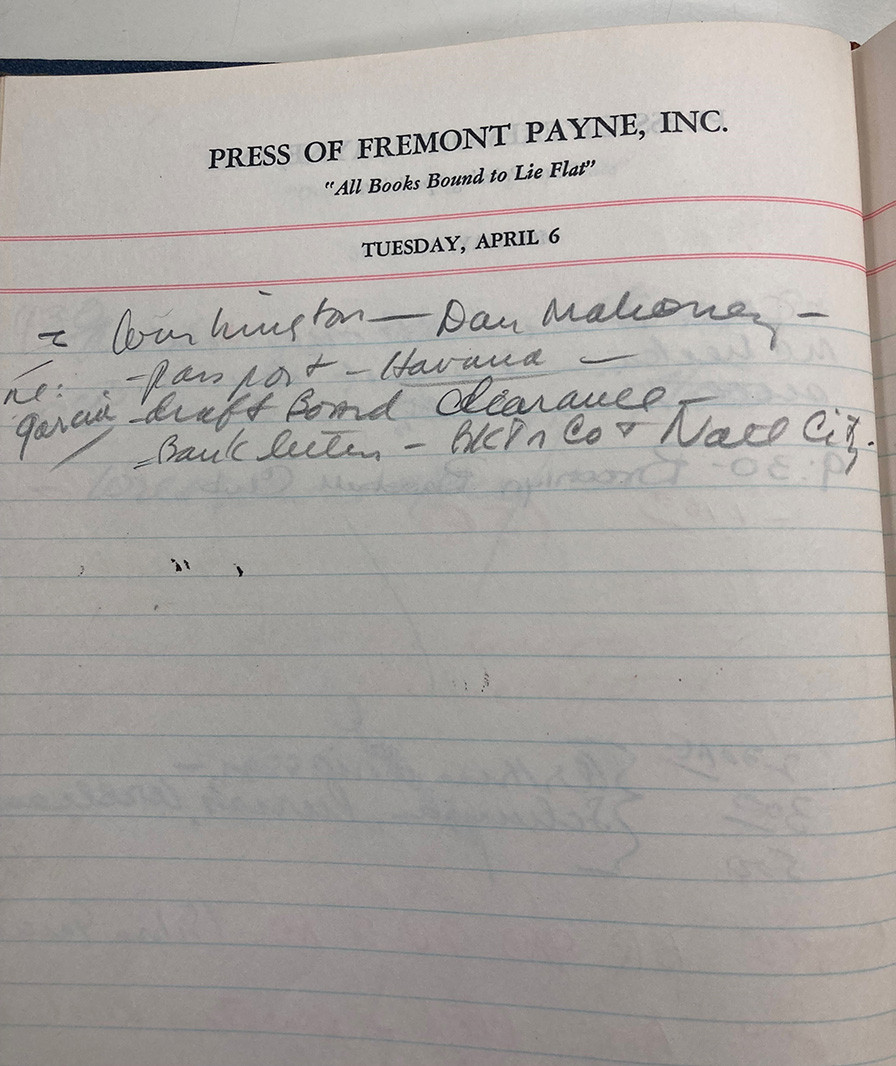

Three days later, armed with a bank letter for the sum of $25,000 (worth about $450,000 today) to cover Garcia’s bonus and purchase price, O’Malley flew to Miami and then on to Havana on April 11. His diary for April 14 read “in Havana – ball game.” But a line was drawn through the latter two words, marking the end of O’Malley’s mission. Garcia, as he discovered arrived in Havana, was now serving in the Cuban military. O’Malley would return to the U.S. the next day, empty-handed.

From Walter O’Malley’s 1943 appointment book, as he prepares for a trip to Havana, Cuba. Dodger President Branch Rickey sent Dodger counsel O’Malley to Havana in an attempt to sign star baseball player Silvio Garcia. Rickey and O’Malley had frequent discussions on signing Garcia. On April 6, 1943, O’Malley writes that he needs a “passport” and “bank letter” for the trip to sign the Cuban of African descent, which would have been a first in Organized Baseball.

Silvio Garcia would go on to have a distinguished 24-year career in the Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, Dominican, Canadian, and Negro National Leagues. His New York Cubans defeated the Cleveland Buckeyes to win the Negro League World Series in 1947. He even became the Class B Florida International League’s first Black player in 1952. But Silvio Garcia never played for the Dodgers or in the major leagues.

Silvio Garcia, a Cuban of African descent, was the target of Dodger President Branch Rickey who in 1943 sent Dodger counsel Walter O’Malley to Havana in an attempt to sign the shortstop. But, O’Malley found out that Garcia was serving in the Cuban military and thus not available to break a barrier in Organized Baseball. Garcia had a 24-year career in various baseball leagues, including Cuban and Mexican.

What if he had? If Walter O’Malley had returned from Havana with a signed contract, Commissioner Landis’s long-standing claim that “Negroes are not barred from organized baseball by the Commissioner and never have been during the 21 years I have served,” would have been put to the test. Landis had always fallen back on the position that baseball integration was a matter for the club owners and not for him. But now that the Brooklyn club was prepared to sign a Black player, here would have been his opportunity to back his words with deeds, or at least with acquiescence.

In 1942 Landis had received a mass petition calling for him to allow Major League Baseball to be integrated that contained a million signatures. With a war underway defined by American political leaders as one for human rights and racial and ethnic equality – what we would today call “anti-racism” – it would have been difficult for Landis to justify a veto of the Dodgers’ move. President Roosevelt had resisted calls to shut down baseball entirely after America’s entry into the war in December 1941, and in a decision that saved team owners millions and may very well have saved Landis’s job, allowed the game to continue for the duration as a morale booster and unity symbol. A rejection of the Garcia signing by Landis, or even a backchannel move against it, would have alienated Roosevelt by interjecting a racial controversy into the national war effort. So it is likely that Landis, would have let the transaction go through, albeit without any great show of enthusiasm.

What then? Garcia would doubtless have faced much of the same overt hostility and racial animus that Robinson encountered in 1947, but as a Cuban national and not a U.S. citizen he might have been able to gain a form of acceptance denied to Robinson as an African American. Light-skinned Cubans had played in the major leagues in the 20th century, notably pitcher Adolfo Luque and catcher and coach Mike Gonzalez, and while they suffered the indignities of “non-whiteness” in a racially stratified American sports environment, they nonetheless broke barriers and paved the way for the next logical step – the signing of a Black Cuban to play in the big leagues. And it was also logical that the Brooklyn Dodgers, in 1943 the only organization in baseball willing to make a commitment to racial equity with what really counts in American life – dollars and cents – would be the team to seek to make that signing. With Landis’s concurrence, and the moral weight of a war being fought for racial justice, baseball’s “great experiment” might have succeeded four years earlier than it did.

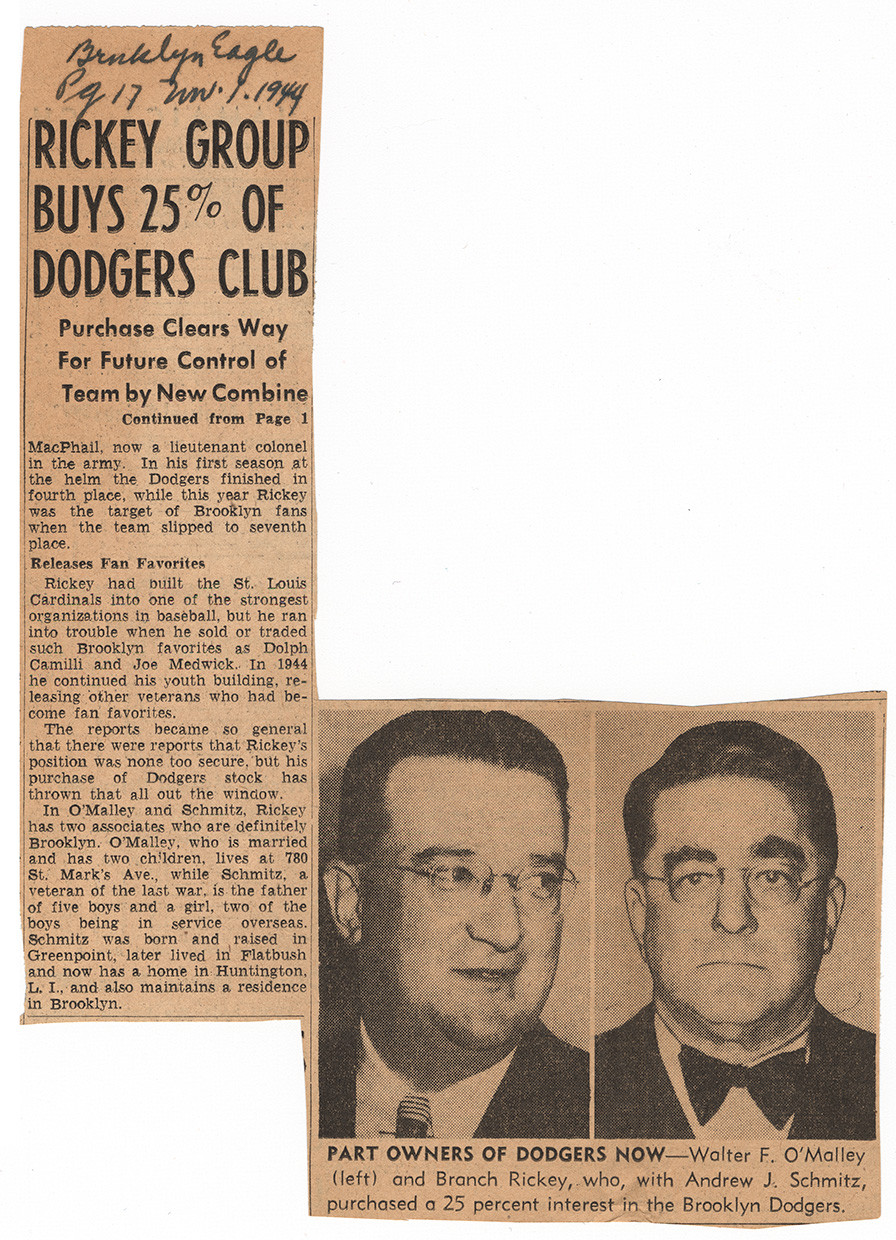

Newspaper clipping showing a jump from Page 1 of the Brooklyn Eagle, November 1, 1944, a year and a half after Branch Rickey and Walter O’Malley’s pursuit of Cuban shortstop Silvio Garcia. Rickey and O’Malley, along with Brooklyn insurance executive Andrew Schmitz, purchased 25 percent of Dodger stock to become equal shareholders. On October 23, 1945, Rickey announced the historic signing of Jackie Robinson to a Montreal Royals contract as the “Great Experiment” began.

Walter O’Malley flew back from Havana in April 1943 without the player he and the Dodgers wanted. But the mechanisms were now in place to make the process of signing, promoting, and introducing Jackie Robinson to the major leagues proceed that much more smoothly. The pursuit of Silvio Garcia insured that in 1947, when Rickey and O’Malley, now co-owners of the Dodgers, brought Jackie Robinson to the major leagues, they would travel over familiar ground. Experiments do not have to succeed to bear valuable fruit. The Garcia experiment would be father to baseball’s greatest one.