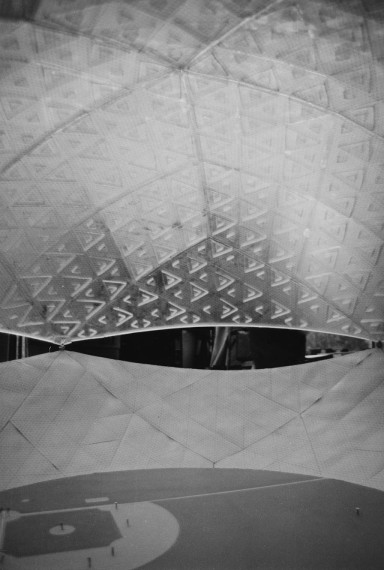

Walter O’Malley and R. Buckminster Fuller peak inside the large scale dome stadium model for the Dodgers in Brooklyn on November 22, 1955. Fuller served as a “guest” lecturer at Princeton University in 1955-56 where the model was produced. O’Malley was intrigued with the concept of a ballpark with year-round events.

Photo by Wil Blanche. Copyright © 1955. All Rights Reserved.

Feature

The O’Malley - Fuller Connection

By Brent Shyer

Shocking, perhaps. Unique, for certain.

As Walter O’Malley searched for solutions to the problem of an aging Ebbets Field with its limited parking in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he dreamed about the possibility of privately building in Brooklyn the first domed stadium for baseball.

Avoiding costly rainouts, ample parking for fans residing in suburbs, year-round uses for multiple sports and improving traffic flow in a highly-congested area were cited as some of the varied reasons that O’Malley was partial to the idea. It should come as no surprise, then, that his vision would cause him to reach out to some of the era’s foremost thinkers and designers.

(L-R): T. William Kleinsasser, Jr., Walter O’Malley, R. Buckminster Fuller, Robert W. McLaughlin, Jr. Walter O’Malley visits Princeton University’s School of Architecture where he meets with inventor R. Buckminster Fuller regarding the design of a domed stadium for the Dodgers in Brooklyn. Fuller’s graduate architecture students worked on the project at the request of O’Malley. The large scale model all-weather dome structure with a translucent roof was one possible design, while T. William Kleinsasser, Jr. also tried to resolve the design problem as part of his master’s thesis with a different domed model. Robert W. McLaughlin, Jr., director of the school, reviews the work on Nov. 22, 1955.

© Bettman/Corbis

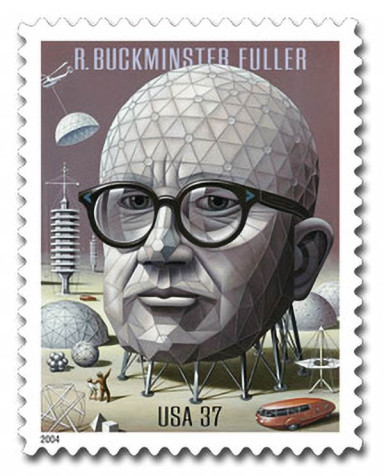

Among those individuals that O’Malley contacted for ideas and solutions was designer, architect, engineer and inventor R. Buckminster Fuller, most famous for his invention of the geodesic dome. A United States Postal Service stamp commemorating the 50th Anniversary of Fuller’s patent of the geodesic dome was released on July 12, 2004.

For his expansive body of work, R. Buckminster Fuller received 47 honorary degrees and was awarded 25 U.S. patents. Fuller was honored by the U.S. Postal Service with a postage stamp, which made its debut on July 12, 2004, on the occasion of the 50th Anniversary of his patent for the geodesic dome.

©2004 USPS

O’Malley pondered the possibility of placing a dome over a baseball stadium for some time. In fact, in his June 17, 1952 letter to Frank Schroth, Publisher of The Brooklyn Eagle, O’Malley wrote: “I believe Brooklyn needs a modern athletic stadium seating approximately 52,000. A modern stadium with a movable roof would provide convention facilities unequalled elsewhere. Such a stadium could house motor boat, automobile, flower, sportsmen and other shows and attractions. Such a stadium would have to be strategically located to give maximum convenience for rapid transit patrons. Present and future parkways should be designed to provide accessibility. The stadium could offer all year round parking facilities.”

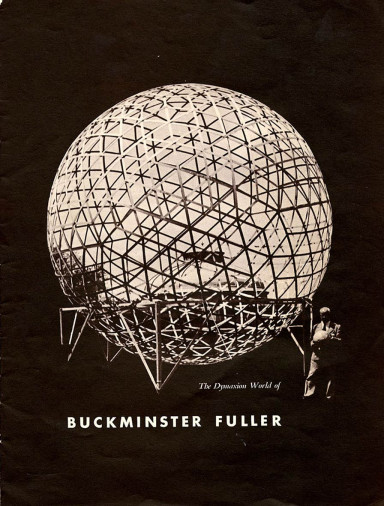

After reading a reprint of a 1953 article “The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller,” American Fabrics, Spring 1953, “The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller” O’Malley wrote a letter to him on May 26, 1955 describing his interest in building a stadium for baseball with a translucent dome. O’Malley’s own educational background from the University of Pennsylvania and his interest in engineering provided him with considerable knowledge of the subject matter.

Whetting Walter O’Malley’s appetite for a possible dome stadium in Brooklyn to replace aging Ebbets Field was an article he read titled “The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller,” which was reprinted in American Fabrics, Spring 1953. O’Malley wrote a letter to Fuller on May 26, 1955 to pursue the idea.

He wrote in the letter, “The dome would possibly have to be tipped off a horizontal axis so that the maximum height was over home plate. The diameter would probably be 600 feet. Such a dome would permit a more satisfactory lighting effect for night games than we now enjoy from the traditional towers in that light fixtures could be placed more strategically. We also plan inverse hanging boxes instead of the usual upper tier and a dome structure would make this quite possible. The average baseball park is used but 65 days a year. Closed-over it could be used, of course, many more times for a variety of events.

“Price would become an extremely important item. A dome such as I have in mind would have to be within the resources of a baseball company, say $1,000,000.

“I’m not interested in just building another baseball park.”

Three weeks earlier, O’Malley wrote a letter to Harold Boeschenstein, President of Owens-Corning Fiberglass Corporation, stating, “As an amateur I have had some experience with small greenhouses and I appreciate that some of the new materials will, no doubt, stand up under New York climatic conditions and it does seem that such a structure on a stadium would almost be a new ‘wonder of the world.’ Our stadium would be generally circular so that the shell would be a section of a sphere.

“If there is anything in the above that intrigues you from the standpoint of the products of your company you might care to give it some thought or perhaps pass it on to some of your technical men and I would be most appreciative to have at the earliest possible moment the benefit of such advice.”

Walter and Kay O’Malley at the family greenhouse in Amityville, New York, where the Dodger President enjoyed spending time cultivating exotic orchids.

O’Malley also wrote to noted architect and designer Capt. Emil Praeger on May 17, 1955. A Navy captain, Praeger had served as the consulting engineer for the structural and foundation design for the White House renovation in 1949 and was considered an authority for bridges, foundations and parkways. They had worked together when O’Malley hired Praeger to design and engineer Holman Stadium at the team’s spring training headquarters, Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida in 1952-53. “I definitely would prefer a translucent dome to one of shell concrete and I did a little pencil pushing, which is enclosed. Look it over and see if it has any practical possibilities,” O’Malley wrote.

One week later, O’Malley again wrote the following message to Praeger, “Enclosed is a copy of letter dated April 18, 1955 to Harold Boeschenstein, President of Owens-Corning...I have just completed a very interesting general discussion with William Keller, Vice-President of that company, and his associates, and I think the trail now takes us to you. Mr. Keller would like to meet with you at your early convenience and discuss some of the problems. It might be that at a later date I should ask Mr. Blancke, President of Celanese Corporation; Vic Williams, Vice-President of Monsanto, Herbert Smith of U.S. Rubber Company and perhaps Chief Wilson of ALCOA, as there are some problems involving fire retarding, quality of resins and pigments to be gone into. For the time being, our problem is one of structural practability and methods of erection.”

Thus, the stage was set for Fuller to jump into the picture and lend his expertise as he responded to O’Malley on June 14, 1955.

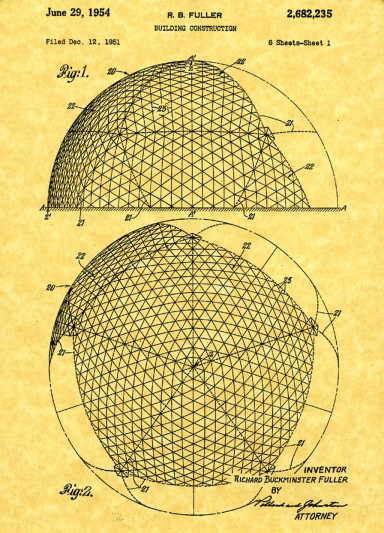

Two views of inventor R. Buckminster Fuller’s 1954 patent for the geodesic dome.

“I am delighted to receive your letter regarding a possible clearspan enclosure for one of your ballparks,” wrote Fuller. “By coincidence, I have already thought a great deal about this subject and have made many calculations in respect to it. About a year ago the Denver Bears (minor league baseball team) asked me to consider the matter seriously and I went through an exploratory design and calculation and came up with the same ‘600 foot diameter and one million dollars’ figures that you mention for the enclosure proper.

“Last fall I was retained as a consultant to architects of Minneapolis who had been commissioned to draw up plans for a Twin Cities ballpark suitable for major league use. In connection with this consultation I studied the critical dimensions and operating service mechanics of the major ballparks and suggested to the architects the use of a specific structural system — the Octetruss — which my company is now employing in designs ordered from me by the United States Marine Corps. The Octetruss clearspan would also provide a comprehensive box seat system vertically and horizontally enclosing the field — to great customer advantage and with increased customer capacity. It would incorporate mass-produced unitarily formed, fiberglass-reinforced polyester-resin, seating boxes, rotatably dumpable for cleaning purposes and impossible to rotate while occupied.

“The vertical Octetruss seating would be wrapped around on the outside with a spiral drive-yourself-up ramp, exteriorly tiered parking balconies. The inwardly canted, interiorly tiered seating boxes would be partially serviced by escalators permitting unprecedented altitude and view advantage.

“The top would be skinned with translucent fiberglass petals opening and closing to the sky. The entire structure would be illumined at night by indirect lighting bounced off its interior sky — enormously enhancing the total visibility for viewers and players alike.

“Enclosed you will find a packet of items which may provide you with a more intimate knowledge of structural problems with which we have been dealing. One of these is comparable in clearspan magnitude to that posed by you, i.e., the 1000 foot spherical radio telescope discussed in the letter to Dr. Emberson of the Associated Universities. The engineering staff and consultants listed in the Emberson letter would also serve with me should you wish to go further with the ballpark problem.”

Initially, many New York elected officials were skeptical of O’Malley’s grand plan for a domed stadium in Brooklyn, but eventually the idea gained some momentum. A later study by the New York State legislature-passed Brooklyn Sports Center Authority supported the concept of a domed stadium for multiple sport uses.

The location O’Malley preferred was at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues, where all subway lines and the Long Island Rail Road depot merged. Besides ample underground parking, O’Malley believed many people would travel to stadium events using public transportation, improving traffic in the congested area (which included the Ft. Greene Meat Market) and make it a shiny new community focal point. Officials of the Long Island Rail Road also endorsed this location. Others, like Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore, who commissioned a study, preferred a location across the street at the same intersection. O’Malley would have accepted either site in order to fulfill his dream of building a new stadium with all of its family-friendly amenities that were so important to him.

O’Malley spent many enjoyable hours in a greenhouse on the south side of his home in Amityville, NY. It helped him to mentally sneak away from stress and the constant barrage of challenges he had to resolve as President of the Dodgers. As a hobby, he and his wife Kay cultivated exotic orchids in their 32-foot long greenhouse. O’Malley, who loved to plant and watch the resultant growth, apparently got the seed of the translucent dome stadium idea from his greenhouse.

The concept for O’Malley’s translucent dome stadium in Brooklyn “was to be supported by a lightweight aluminum truss structure some 300 feet above the pitchers mound, high enough to cover a 30-story building.” It would have enabled sunlight to shine through, much the same as a greenhouse.

Courtesy of Department Special Collections Stanford University Library

“A dome constructed of a translucent material would eliminate shadows and give a pleasant interior effect of the sort one finds in a greenhouse,” O’Malley said in a 1955 Dodger press release. “Such a structure would make it possible to have controlled temperature inside, even in modern stadia of which Milwaukee’s County Stadium is a recent example. Too many people wind up behind posts and columns nowadays and they won’t accept these seats. This condition would not be true of the new park. The fans are our responsibility. We lost 200,000 attendance by adverse weather last season.”

The proposed stadium, with underground parking for thousands of cars, included 52,000 unobstructed view seats, with some 7,000 seats in hanging boxes suspended from the structure.

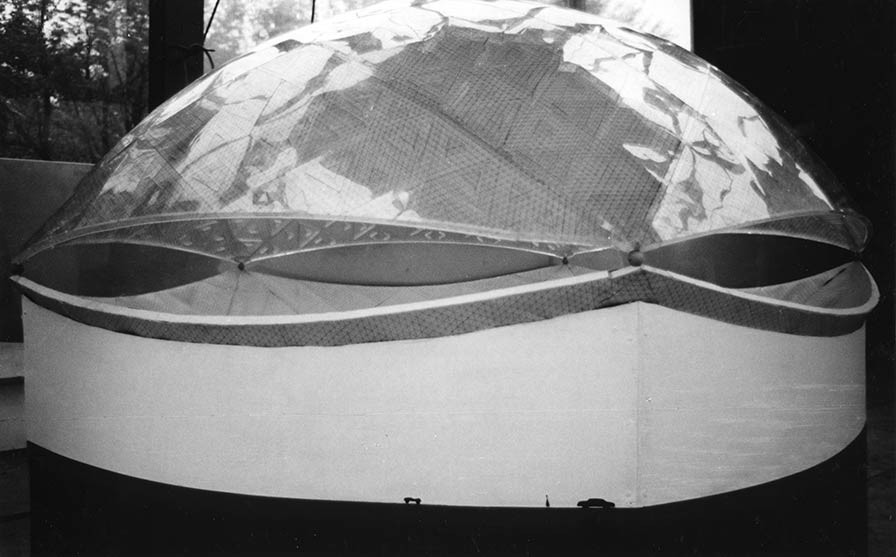

One of Fuller’s 1/2-geodesic spheres was at Huntington Station, Long Island, NY in August, 1955 and O’Malley and some friends asked to test the 55-foot clearspan diameter dome by throwing rocks at the plastic structure. If baseballs could possibly hit the top of a similar dome, O’Malley wanted to know the effect. Fuller granted permission to them to throw rocks according to a Dodger press release and “despite the explosive sound of the impact no damage to the dome resulted.” Thus, another hurdle was cleared.

Fuller further assisted the Dodgers through his graduate class at Princeton University, where he was a “guest” lecturer. Fuller’s class of architecture graduates worked on possible solutions to the dome stadium problem for O’Malley. The efforts led to a model of a dome stadium that Fuller and his students presented to O’Malley on November 22, 1955. While Fuller oversaw the construction of the large dome model by the students, another model was presented to O’Malley which also caught his attention.

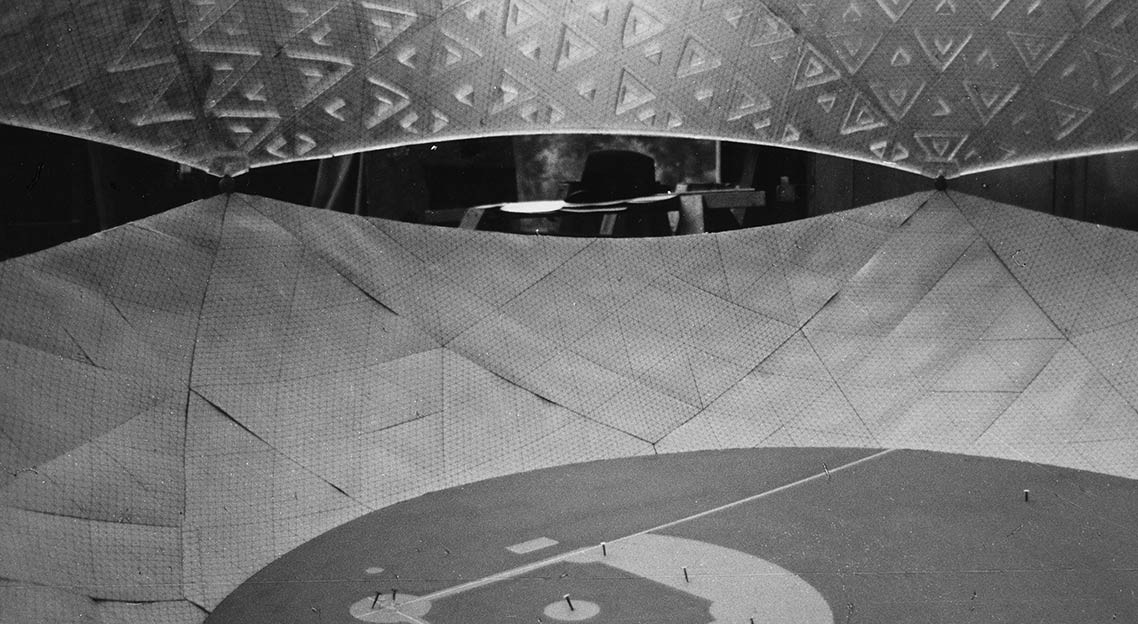

Another view of the large scale dome stadium model, produced by Fuller and his graduate architect students at Princeton University, for the Dodgers in Brooklyn. Miniature players even took their positions on the mock field.

Courtesy of Department Special Collections Stanford University Library

It was designed by T. William Kleinsasser, Jr., an architectural graduate student who unofficially attended one of Fuller’s lectures and took on his challenge to design a model of a ballpark for the Dodgers, which had to include a practical dome. Kleinsasser, who made the project his master’s thesis, did design a dome model as an alternative to the one produced under Fuller’s guidance with assistance from his students. O’Malley was impressed with Kleinsasser’s work, which even included “a small sightseeing tramway over the top of the dome” according to the July, 1956 issue of Mechanix Illustrated.

Upon reviewing the dome stadium models in his visit to Princeton, O’Malley said he was “thrilled with the work.” New York Herald-Tribune, November 23, 1955 However, despite newspaper accounts that O’Malley had engaged Fuller’s Synergetics, Inc. laboratories in Raleigh, NC and Cambridge, MA to begin calculations for a 52,000-seat stadium, he had, in fact, done no such thing. O’Malley was annoyed with the erroneous reports, because his engineer was Capt. Praeger of Praeger and Kavanagh, who would eventually accept or reject the geodesic dome stadium concept with input from leading experts like Fuller. If it were to be built, Praeger would be the chief engineer and contract out the dome.

Fuller’s assistant John Dixon contacted Westinghouse Electric Corporation on behalf of Fuller with the following information about lighting for a dome: “Please tell Mr. Kaswin (of Westinghouse’s Engineering Service Dept.) the lighting is to be of two kinds — visible and invisible. Both lightings are to be indirect, i.e., bounced off dome’s interior. Visible lighting to be economical cool inert gas-filled tubes. The invisible lighting to be of infra-red heat radiation producing elements. This concept was Mr. Walter O’Malley’s own and is extraordinarily practical. Concave surface of dome will re-converge both cold and warm radiation to concentrate on spectator-player areas. They will be photo-electrically and thermostatically automatic in regulation. As dome luminosity decreases, internal lights will take over with almost invisible transition.”

Another view of the large scale dome stadium model, produced by Fuller and his graduate architect students at Princeton University, for the Dodgers in Brooklyn. Miniature players even took their positions on the mock field.

Courtesy of Department Special Collections Stanford University Library

On May 1, 1956, O’Malley thanked Fuller in his note, “I was pleased to receive a copy of letter John Dixon wrote to Mr. Kaswin. It was interesting to see the thought expressed in scientific language. You will be curious to know about all recent developments so let me know when you will be finished with your lecture tour and free to go to a ball game.”

Over the course of the next several years, the O’Malley and Fuller friendship continued as they met and corresponded on numerous occasions. Even as hope was fading by O’Malley that he could build his domed ballpark in Brooklyn, on April 15, 1957, he wrote an internal file memorandum stating, “Of great interest, however, is the fact that (Robert) Moses (Parks Commissioner for the City of New York) said he was now 100% for a domed stadium. This is again significant. It represents quite a concession on his part but he apparently is so enthused about it that we might be able to convince him that he thought of it first. I doubt if we would have any trouble with the Yankees in moving that close to their stadium and I am sure the Giants would not give us any difficulty as Horace Stoneham has already indicated to me that he intends to move to Minneapolis whether the Dodgers stay in New York City or not. Bob Moses would want us to pay a rental that would amortize the cost of the improvement in 20 years. This might be more than we could chew particularly if the stadium were to go as high as his figure of $10,000,000 indicates.”

When the Dodgers were subsequently unable to secure the land on which to build the dome stadium, as Moses later kept pointing them away from Brooklyn and towards Flushing Meadows, Queens, NY, O’Malley looked for other solutions and considered Los Angeles. After last-ditch efforts by New York elected officials to keep the Dodgers failed, it was announced on October 8, 1957, that the Dodgers committed to Los Angeles and the need for a dome stadium was gone.

Or was it? At least the mild Southern California weather would make it unnecessary. But according to O’Malley’s correspondence, he did consider at least a partial dome in Los Angeles as he wrote to Fuller on December 12, 1963, one year after privately-financed, 56,000-seat Dodger Stadium had opened.

“Life is full of coincidences. On my return from Africa last week I thought that I would like to explore with you the possibility of erecting a section of your geodesic dome from the outer dimensions of the skinned area of our infield up to the bottom elevation of our reserved seat stands thus enclosing the horseshoe behind home plate. This would give us a ground area big enough for basketball and hockey games and as these events for the most part take place after the close of our baseball season it could be a good additional activity for our stadium and I believe we could get about 20,000 seats in the enclosure. The structure, of course, would have to be of a type that would be demountable and the cost factor naturally would be of great consideration.”

Fuller responded by letter on December 27, “Your infield basketball, hockey, 100% demountable dome is completely feasible. Our international trade-fair dome’s structural principles are directly applicable. Our trade-fair domes are traveling around the world, in many countries for the government. We have just assembled a 200-foot diameter dome of this class for the N.Y. World Fair Corp. as their reception pavilion at the main gate.”

While this never did materialize, O’Malley always seemed intrigued with the idea of the geodesic dome, as on June 1, 1967 he wrote to Fuller again stating, “One of these days we will have to plan to have our paths cross as I am mentally stimulated to have a chat with you. My memory is also a long one and I recall our many conversations about your theories and particularly the geodesic dome.

“I still think that there is a possibility of putting up a segment of a dome that would cover the infield area of our stadium up to the third level so that we would have an enclosure for ‘indoor’ sports after the baseball season. Of course it would have to be of a demountable type. We are thinking of installing ice skating facilities in that area for the off season months.”

Walter O’Malley, President of the Dodgers, reviewed the proposed Harris County Sports Stadium, better known later as the Houston Astrodome, on October 18, 1960 when the National League owners voted to grant Houston and New York franchises. Along with O’Malley at the meeting were (left to right) Robert Carpenter, Phillies owner; Gabe Paul, Reds General Manager; Phil Wrigley, Cubs owner; and Joe L. Brown, Pirates General Manager.

Courtesy of University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Specialized Libraries and Archival Collections

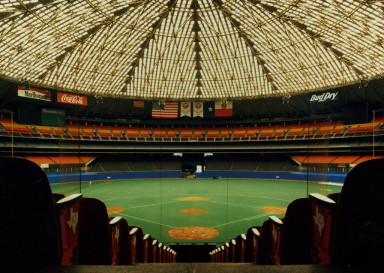

The Astrodome in Houston became the first dome stadium for baseball when it opened in April 1965 at a cost of $35 million. O’Malley had been asked by officials in Houston to share his years of research and expertise on the topic of the dome stadium which he willingly did for Judge Roy Hofheinz, owner of the team, a county judge and former city mayor.

Fuller spent two years working with Judge Hofheinz to develop the concept of a dome stadium in Houston, but was not directly involved in its execution. On May 23, 1967, he wrote O’Malley, “Despite your warm friendship and help, Judge Hofheinz, after realizing through you and after my subsequent visits with him for two years that such a dome was possible, employed contractors who took a license under my patents but so modified their designs so that their design would not read on my patents.

“They thus avoided paying me royalties but made their dome so much heavier that it not only cost much more than it should, but also, the profile of the cross sections became so much wider as to bring about the impairment of optical facility in following baseball. As I planned his stadium, the structural members would have been so delicate as to be as relatively invisible individually as are the wires of a fly-screen when seen from about twenty-five feet. Such a screen at such a distance does not in any way impose the requirement of optical adjustment to its relative blackness with subsequent readjustment to white, bright light.

The Houston Astrodome, built at a cost of $35 million, was home to the Astros from 1965-99. Before building the Astrodome, Houston owner Judge Roy Hofheinz consulted with Walter O’Malley and what the Dodger President had learned from his early study for a dome stadium in Brooklyn.

Barry Howe Photography Copyright © 1992

“As you will remember, before my dome, Saint Peter’s Dome in Rome with one hundred and fifty foot diameter was the largest dome realized by man or thought by engineering to be practical anywhere around the world in all history. The minute that I began to demonstrate my geodesic domes, even the small ones, engineers who saw the demonstration of its practicality and feasibility began to promote their use where such strategy might bring large business to their professional practices. At the present time, there are hundreds of engineering offices competing for domes to span baseball stadiums.

“Because I am a scientist and nothing can corrupt the effectiveness of a scientist more than his engaging in the promotion of his discoveries, I do not compete. I only give service when I am asked to give service. Now that many are contemplating covering stadiums and they are besieged by so many aspiring engineering firms and contracting companies, none of the potential owners of the domes get in touch with me or ask my advice. All the time, however, my own experience increases. I have built over five thousand domes in fifty-one countries in the past seventeen years...

“I am only allowed to talk to you about domes because you first came to me about domes.”

In October 1966, Fuller sent a note to O’Malley wanting to take his grandson Jaime Snyder to the World Series at Dodger Stadium. He wrote, “Congratulations, magnificent Walter. Averaging one penant (sp.) every two years since we started dome talks fourteen years ago in Borough Hall.”

In his May 23, 1967 letter to O’Malley, Fuller commented, “I was sad not to be able to see you when, with my grandson, I occupied the box seats that you made available to me for the World Series last year. I was shocked to learn of your most untimely ill health. With warm affectionate and admiring regards. Faithfully yours, Bucky.”

The aftereffect of the Fuller and O’Malley connection? A young New Orleans businessman named Dave Dixon, a Tulane alumnus and a marine in World War II, remembered reading a note in The Sporting News about Fuller working with O’Malley on a proposed dome stadium for baseball in Brooklyn. Dixon took that idea and his belief that while the Astrodome was just a “covered baseball field,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, “Superdome, Saints Among Dave Dixon’s Louisiana Legacy” by Marty Mule. it was really not a good multi-purpose facility.

The Louisiana Superdome was the brainchild of New Orleans businessman Dave Dixon, who had the vision of building the finest dome stadium with year-round events. As a young man, Dixon read about Walter O’Malley’s interaction with R. Buckminster Fuller to design a dome stadium in Brooklyn. Years later, Dixon built the Superdome and was also the driving force in attracting the NFL to New Orleans in 1966.

© Bettman/Corbis

Dixon wanted a gem of modern and urban architecture to be erected in New Orleans, but he had a difficult time convincing locals of his plan in the mid-to-late 1960s. He worked tirelessly to pass a bill with the Louisiana Legislature in 1966 which permitted the stadium to be built. That same year, the NFL awarded a franchise to New Orleans. On Dixon’s brainchild, the facility which came to be known as “The Superdome” opened on August 3, 1975.

“The origin of the Louisiana Superdome really was with Walter O’Malley,” said Dixon, now retired in New Orleans. “That’s where I got the idea from reading a story in The Sporting News. A dome stadium in New Orleans makes great sense where you could air condition and have it covered in case of rain. We get a lot of rain here and it would make summertime activities a whole lot more pleasant.

“I had a very nice visit with Walter at Dodger Stadium. Then he invited me to join him for dinner that night, which I did, along with some other major Hollywood people who were in his suite at Dodger Stadium. I enjoyed myself. I was the initiator of the Superdome here in New Orleans. I got our governor, a wonderful man named John McKeithen, who never wavered and we got this thing built and it’s the most magnificent building, I think, in the country. Some of that really comes from swapping ideas with Walter. It’s a major facility that’s probably used 365 days a year for various events. We had a good long session in Los Angeles. I thought he was a very kind, good man. He made a wonderful impression on me.”

To learn more about R. Buckminster Fuller, visit the Buckminster Fuller Institute.