Dodgertown Memories

Maury Wills

- Shortstop

- 1959-66, 1969-72

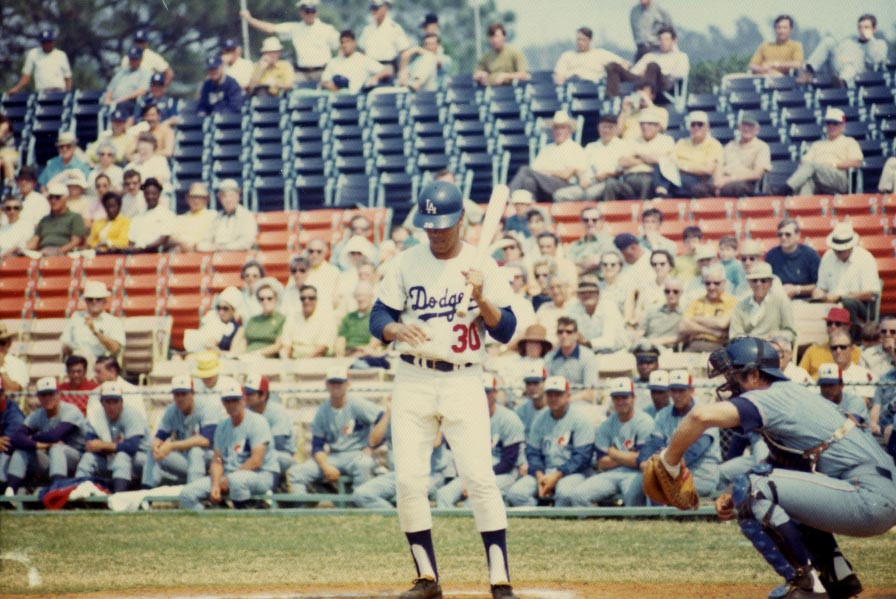

Maury Wills returned to the Dodgers in June, 1969 and is shown playing a Spring Training exhibition game at Holman Stadium, Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida against the Montreal Expos, his former team, circa 1970. It was his second stint with the Dodgers after eight and a half years in the Dodger minor leagues before he was elevated to the Dodgers in 1959.

Perseverance and triumph are characteristics embedded in Maurice Morning Wills, who grew up in the projects in Washington, D.C. with 12 brothers and sisters. After toiling eight and a half years in the minor leagues, compact Maury Wills had a breakout season in 1959, when he joined the Dodgers midway through the season and helped them win their first World Series Championship in Los Angeles. Originally drafted as a pitcher in 1950, Wills quickly shifted to an infielder his first spring in 1951 at Dodgertown which launched his career. From that point, the slick shortstop helped to bring back to baseball the lost element of speed, as he led the National League with 50 stolen bases in 1960. By 1962, playing at new Dodger Stadium, Wills was running wild to the encouraging fan chants of “Go, Go, Go!” to a then major league record 104 stolen bases, topping Ty Cobb’s major league record of 96 in 1915. Wills was also named N.L. MVP that season. He led the league in stolen bases every year from 1960-65. Dodger Manager Walter Alston named Wills as the team captain from 1963-66. Wills also sparkled at shortstop, winning back-to-back Gold Gloves in 1961-62. He played in four World Series for the Dodgers, helping them to win three World Championships (1959, 1963 and 1965). Wills was a member of the Dodgers’ all switch-hitting infield in 1965-66 with Wes Parker (1B), Jim Lefebvre (2B) and Jim Gilliam (3B). Following his playing career, Wills has served as a major league manager (Seattle, 1980-81) and as a minor league instructor, specializing in the arts of base stealing and bunting. An accomplished banjo player, who has performed in Las Vegas hotels, Wills spent six years as a baseball analyst for NBC Sports. He also spoke frequently to groups of young people about the ills of drug abuse. Wills passed away in Sedona, AZ on September 19, 2022.

Maury Wills (right) was invited by Walter O’Malley to play the banjo at one of the renowned St. Patrick’s Day parties at Dodgertown, circa early 1970s. He is joined by teammate Tommy Hutton on the guitar.

I got on this coach train (in Washington, D.C) and it took me about two and a half days, just rocking back and forth sideways, looking out the window the entire time, maybe sleeping a little at night, but mostly just looking out of a window. We finally stopped in Vero Beach. got off with my little cardboard box with my twine around it with my baseball stuff in it and a few clothes in a duffel bag and a man came over, knowing who was supposed to be on the train and got me and a couple of other players and put us on this little old bus that they had with the engine protruding out front – an old school bus, dilapidated and everything else, but it had ‘Dodgers’ on it; that was cool. And now I’m going to Dodgertown! They took us out there and checked us in and gave us a room and there were eight in a room. They had the military cots, top deck and a bottom and there were four of those in a room. Eight players in that one room and the restrooms were down the hallway. It didn’t matter. Even a two and a half day train ride was wonderful.

“At that time, the Dodgers had about 25 farm clubs – I was in the lowest of all ‘Class D’. We had about five ‘D’ clubs. I remember the first day out there, the next day, they assembled all the Class D clubs on one baseball field way over by the airport at Dodgertown. That was diamond number five. They asked all the players to go to their respective positions and they only had a few first basemen and a few shortstops, a few right and center fielders and catchers and a horde of pitchers, big farm boys. I mean I’m only about 5’9”, 155 pounds, but I could throw a ball through a wall. I was signed as a pitcher. I’m over with all those pitchers. Even at that time, I had the presence to look for an edge. That was my whole career, looking for the edge. I noticed there was nobody at second base, or maybe just one. I went to the minor league coach and manager and said I can play second base, which I could because when I wasn’t pitching I was playing shortstop. I said I can play second base. He said, ‘You can? Go on over there.’ I went over there and I never pitched. I played second base and I went off and played my first year and stole 54 bases and I hit .280. I just had a good year as a first-year player. They sent me back to Hornell (N.Y.) and I stole 54 bases and hit .300. Then they sent me to Class A Pueblo.

“Every time I went back to Dodgertown, I stayed with seven other players in the barracks. The minor leaguers stayed in one section and then a road was in between and then the major leaguers stayed over on the other side. The major leaguers each had a room to themselves with a restroom in between and then a roommate on the other side, so it was like a mini-suite. You actually had your own room. The dream of every minor league player was to get over into that major league complex. That was my dream. It wasn’t about how much money I could make, it wasn’t about anything other than getting over there with them and that was the way I was going to get to Brooklyn with Jackie (Robinson). We didn’t get to see the Dodgers much, because they went to Miami to play. They came back to play maybe three or four games out of the entire spring at Holman Stadium. You talk about some bug-eyed minor league players who were aspiring to be major leaguers, we were just gawking at the major leaguers – Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Duke Snider, Pee Wee Reese, Joe Black, Don Newcombe, Jim Gilliam later on, Carl Furillo, Carl Erskine, Clem Labine, all down the line, just to see them. They would come in the dining room and we had to stand aside and let them get served first – with the metal trays with the sections in them. They were bigger than life, you didn’t dare approach them. It was kind of an unwritten rule, I mean you just don’t approach a major leaguer and say hi.

“I felt I was making progress. I loved the game. Baseball is my passion and still is. As long as I was playing, I knew that I was on the way to going to Brooklyn, as long as Jackie kept playing and as long as I kept improving. I never felt like my second or third year that I was ready to be there and they were just holding me back. I was always positive.

“The day I got back to Dodgertown (after being sent back by the Detroit Tigers during Spring Training in 1959), they had the big race over there. We used to race all the time on the track. The race track was right down by diamond number two, right over where the half diamond is now. They had Tommy Davis, Willie Davis and Earl Robinson, who was out of the University of California at Berkeley who they thought was going to be the next Jackie Robinson. He got a big bonus, like $30,000 in 1959. He could fly. They had this big race and they threw me in there. Who was starting, but John Carey, the man that was in my living room signing me for $500 or some clothes (in 1950). Everybody was there. I went over to John Carey asking him how are you going to start it? He said, ‘Take your mark, set, go.’ Just like that. I never lost a foot race. I beat them on the start. When John Carey said, ‘Take your mark, set…’ bam, I was gone. I knew the gun was coming. They use a gun with blanks in it. They were waiting to hear the sound. I knew the sound was coming. I won that race. To this day, Tommy Davis and I and Willie argue about it. It was a 6.1 60-yard that I ran.

“1959 was my rookie year. I’m going back to Dodgertown in 1960. The big thing was that I was going to be over in the barracks with the major league players. That was the whole thing. Jackie was gone by that time. But, I did make it to the big leagues. Too bad he wasn’t there, but I’m here and I’m going over in the major league barracks. They put me back in the barracks with the minor leaguers, eight in a room and I cried like a baby. I was really sobbing, with gut-wrenching knots in my stomach and pain, ‘Why? I’m a major leaguer.’ I had to win the job again. I worked hard. I didn’t know until the day before Opening Day that I was going to be the starting shortstop. That’s when I came out and I changed the game. I stole 50 bases – unheard of -- and hit .295, I was in the top 10 hitters. I had a good year and then I’m going back to Spring Training (in 1961) and I’m going to be with the major leaguers. That was the big thing. I didn’t care what (G.M.) Buzzie (Bavasi) was going to give me for a salary. I got $12,000 my second year. I thought I was rich. I got to the major league barracks for the first time. I felt like I had gone to heaven. John Roseboro was in my suite. I had my suite and we had a restroom in the middle. I had my own room for the first time.

“The Dodgers had a way of not letting you get complacent. They had a way of making you stay hungry. They knew I was going to be on the team, but they wouldn’t let me know it. I worked hard in Spring Training in 1962 and that’s when I changed the game totally, stole 104 bases, MVP and got the number one professional athlete Hickok Award, beating out Arnold Palmer by one vote.

“By this time, I’m playing the banjo. After the 1959 World Series, I went back to Spokane where my family was. My family and I decided to stay there because that was the last minor league town that I played in. One night shortly after I got back home, I was in a Shakey’s Pizza Parlor, this honky tonk place with sawdust on the floor. There was a banjo player in there. I heard this man play the banjo and I knew I wanted to play the banjo. Before that, I used to play the ukulele. Banjo music just does something to you. He referred me to his teacher. I went eight straight years without missing a day touching the banjo. Now I’m playing the banjo in Spring Training and Mr. O’Malley heard about it and so he asked me if I would play at the St. Patrick’s Day party. I said, me play the banjo? I said I can’t do that. I’m not good enough. He said, ‘Well, I think you are. I heard you.’ I said I really don’t want to. He said, ‘I’ll pay you for it.’ I said, you will? He gave me $100 a tune. I said okay. After I played about three, he made me stop, he said ‘That’s enough.’ He signed one of the dollar bills for me. It was his own idea. He said ‘To Maury, the highest paid banjo player in the world! From Walter Francis O’Malley.’ I wish I had that dollar bill. I’m thinking that’s about 1962. I did it every year after that. They still ask me to play down there.

“Everything that I teach to players today, I learned from Al Campanis back in the early ’60s. I haven’t changed a thing. The bunting came from Bobby (Bragan), the base running and the base stealing came from Al. We had lectures all the time down in Spring Training. We had lectures on outfield play, infield play, hitting, catching, pitching and base running and they included base stealing with the base running. Whenever they had those lectures, especially the ones pertaining to running, stealing and bunting, I was always in the front row. I paid attention even to outfield play, infield play (naturally, I was an infielder so I paid attention to that), but I paid attention to outfield play and I went to the pitchers, too, because I wanted to learn the entire game because I think it is all connected. If I know how the pitcher is thinking, you see that even helped me in my base stealing to know what a pitcher is thinking. I learned what the opposing pitcher is thinking from my own pitchers and what they were going through, I knew the other guys were going through the same thing. I got all of that at Dodgertown. After I stole 104 bases in 1962, Al had me give the base running lecture as a player. I said no, I’m a player. He said, ‘Go ahead, you do it.’ I said okay and I’ve been doing it ever since. I learned it all in Dodgertown and I’ve never changed a thing.

“I’m going to really miss it (Dodgertown). Because, at the point I’m at in my life now, over 50 years now, the thing that keeps me going is my passion for the game and for the Dodgers, for Dodgertown, Dodger Stadium. Spring Training at Dodgertown is like a college campus. The dining room, the laundry room and all of the nice people at the front desk, all of the grounds crew, the maintenance people, I know them all personally. I go to the country clubs to play there. When I first went to Dodgertown in the early ’60s, I couldn’t. It was difficult even going into town because of the laws. Today, I play as a guest of the local country club. The general manager of the local country club comes to Holman Stadium as my guest and things like that. I go to places where they won’t even take any money from me anymore in Vero Beach – restaurants, golf courses. Dodgertown meant more than just baseball.”

Maury Wills